A NIGHT IN ARMKHI

Welcome the Armkhi Hotel

It was late in the evening when we arrived in Armkhi from our evening meal at the homely little Mountain Legends Cafe-Hotel, in the remote mountains of southern Ingushetia.

Once again, we had checked out our hotel in Armkhi and on-line it looked splendid; an enchanting chalet styled building set on steep high mountain slopes and smack in the middle of a mystical fir forest. The photos looked like something out of an alpine fairy tale setting. Sadly, the hotel was not quite as good as it looked.

Wary of our expectations after our Grozny incident, poor Abdullah took great pains to explain well beforehand that the place would be basic.

On unlocking our door, he went straight to the light fittings, most of which had no bulbs or were broken. Electrical cables were hanging out of the walls and the only way we could flush the toilet was to take the lid off and depress the cistern float manually. Disappointed he apologised "It looks like there has not been too much maintenance on this building".

It was such a shame. Our hotel room was actually rather lovely, featuring raked ceilings with an unusual high inset triangular gabled window. And the room had the most stunning views of the surrounding mountains, valleys and impossible zig zag roads.

Yes, it was basic but it was clean and comfortable - and bliss, it had an electric kettle, and cups and saucers. It would do us fine, we assured a rather relieved looking Abdullah.

After Abdullah left we realised however that we didn't have any bottled drinking water. "Don't worry, the Scotch will disinfect it anyway" said the ever-practical Alan. I was not to be deterred.

Armed with my hard learnt Russian language skills I headed for the kitchen. I would have thought it well within my capabilities to ask for two bottles of water, but I was not at all successful. The obliging young man at the reception just looked at me, totally confused. In the end I spotted a drinks refrigerator and pointing through the door, settled for two bottles of Coca Cola. Scotch and Coke? Well, I guess so... Then when I tried to pay him, I caused even more trouble. I hadn't learnt the words for "I'll pay for these tomorrow morning". He looked relieved when I left.

Walking back to my room, I consoled myself. I had tried so hard. Perhaps it was my poor Ingush accent? After all, our previous Chukotkan guide and good friend Alex always joked that I sounded like a Ukrainian....

Discussions Over a Relaxed Breakfast - The Armkhi Ski Resort

Some of our nicest and most interesting times were spent just talking with Abdullah. Over a relaxed breakfast the next morning, we discussed our hotel which was in fact a ski resort in winter as well as a balneological and mineral springs health centre. Only opened in 2013, it was planned the resort would attract skiers, hikers and holiday makers from all over Russia, as well as internationally.

The hotel itself seemed well set up, offering hot baths, saunas, a large heated swimming pool and very pleasant garden terrace. The skiing facilities we understood were apparently very good; equipped with a 1,200-meter ski run, ample chair lifts and ski facilities for disabled. And up to 1,000 tourists could be accommodated on any one day. The surrounding area also offered good cross-country skiing as well as plenty of opportunities for hiking and fishing. And it certainly was extraordinarily picturesque.

Why the maintenance was so slack was however beyond us. It did make us wonder just how successful a resort business Armkhi really was. In a number of on-line articles about skiing in Ingushetia, it was pointed out that the region is still not considered stable enough to attract large numbers of tourists, even though price wise it is very competitive - and beautiful.

Of course, this is the same issue with all tourism in the region, especially in the eastern parts of the North Caucasus. Perhaps one day, poor little Ingushetia would have her day in the sun. We hoped.

Ingushetia's Ongoing Border Disputes

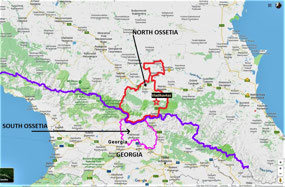

Our discussions about the seemingly impossible hardships endured by Ingushetia and indeed many of the Caucasus regions, led us onto the ongoing border disputes in the tiny republic.

And if you look at a map of Ingushetia it looks rather like a decayed tooth with lumps eroded out of it on all sides, especially on its western front where a gaping hole which was once the Ingush territory of the East Prigorodnyy District, is now part of North Ossetia-Alania.

More recently however, the Ingush have been disputing a newly proposed border with Chechnya to the east. Surprisingly, there have been no officially demarcated borders between Ingushetia and Chechnya since the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic (ASSR) split into two Russian federal subjects shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. And that very uncertainty has led to multiple territorial conflicts ever since.

The new proposal approved on October 4th 2018 by Ingushetia and Chechnya gives Chechnya some 7% more of Ingushetia's territory. And no wonder the Ingush are angry. If it wasn't bad enough having Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov's attempts to claim Ingush territory, it was even more devastating to the Ingush that their leader Yunus-Bek Yevkurov* who had signed the deal, was trying to change the constitution to eliminate the need for popular vote on territorial changes. Not surprisingly, demonstrations and violence broke out on the streets mainly in the capital of Magas, but also throughout Ingushetia.

Meduza Real Russia Newsletter comments: "As Ingush citizens protested, first against the deal itself and then against the government’s attempt to eliminate the need for a popular vote on it, both the region’s intelligentsia and Islamic fundamentalists took part. By April (2019), that struggle against municipal, regional, and federal government forces had become a war of entrenchment: law enforcement agencies began searching and arresting opposition activists en masse". Meduza, April 2019.

* Following elections on 26th June 2019, Muhmud-Ali Kalimatove is now President of Ingushetia for a five-year term.

We sighed. It seemed Ingushetia still had a long way to go with its internal and external political issues. Stability it appears, is always just out of reach for the troubled republics of the North Caucasus. We were realising that we were only just beginning to gain the merest snippet of appreciation of the culture, history and politics of these complex regions.

TO NORTH OSSETIA-ALANIA

Toward the Georgian Border. Reminiscing About Our 2015 Travels.

Our program for the day was to travel west from Armkhi, crossing the border into North Ossetia-Alania, then travelling through the southern mountainous country of the West Prigorodnyy District to the ancient burial site of Dargavs and then to the Dzigviz Fortress, near Fiagdon. We would then skirt the Tseyskiy Godsudarstvenny State Park to our west, heading north-east to Vladikavkaz where we would be based for the next two nights.

We had not realised until then that we would not be travelling in the sensitive East Prigorodnyy District, a former hot bed of discontent and the trigger for the Ossetia-Ingush Conflict of 1992 (refer previous entry "Ingushetia: An Economic & Historical Briefing).

Like a lot of our travels in the North Caucasus, we had no information as to the rationale of our itinerary. It could well have been for safety reasons we skirted some areas or spent very little time in others. One thing we knew was that if Abdullah did know, he was not going to share the information with us!

As we drove out from Armkhi, I finally asked Abdullah the question that had been intriguing us for the five days we had travelled together - but to which we did not really need, not want a direct answer. "Well, where are the terrorists and the kidnappers?". He laughed quietly "Well...." he said slowly as if he was thinking through the answer "I think they may be in Moscow....". We didn't bother asking again. And it was true. We didn't really want to know.

We were in North Ossetia before we realised we had even crossed the border. Once again, we felt somewhat disappointed we had spent so little time in Ingushetia, for which we had developed a real soft spot. Pristine, wild and immensely haunting, the tiny land of watch towers was one of the more beautiful and fascinating regions we were to discover on our travels.

Abdullah asked us if we would like to travel down to the village of Lars to see the Georgian Border. It was only just kilometers from the junction of the road from Armkhi and the Georgian Military Highway. We were very fond of Georgia and thought it may be interesting to see it from "the other side".

Over the last days, I had thought a lot about our Georgian guide Keti and our driver Vano who had provided us with such a good time during our travels in Georgia.

Keti, a sweet natured, vivacious young woman who at the time was doing her PhD on religious historical buildings, had an unstoppable passion for history, wildflowers and the environment - and would have loved Ingushetia. I could still see her running out into the high meadows of Georgia, taking endless photos of some obscure tiny flowering plant.

And all the while, Vano in his quiet fashion would just smile slowly shaking his head as Keti danced with delight at some piece of nature she had discovered.

A reserved yet interesting man, Vano who lived right on the edge of the South Ossetian-Georgian border, often talked about the ongoing disputes between the two nations. "There are South Ossetian snipers who regularly take pot shots at the people across the border. Even at the school children" he said sadly.

One day, Vano invited us to his family home for lunch, and we were both delighted and deeply appreciative of his offer. On that morning however, Keti carefully explained that her boss had refused to allow us to visit his house on grounds it was too unsafe. While we could appreciate her manager's concern and were grateful for the caution, the look of immense disappointment on Vano's face was gut-wrenching. His wife had apparently gone to no end of trouble, preparing us a lunch which included killing and cooking one of their own chickens, and which we would now pick up from his son at a petrol outlet to have a picnic somewhere on our way instead. It was even worse as we knew that Vano and his family were not wealthy people. We often think about this lovely man.

Verkhniy Lars - Last Village Before the Georgian Border

Lush forested scenery interspersed with tiny cottages and patchwork farmlets greeted us as we drove toward the turn off from the Armkhi Road and south down the famous Georgian Military Highway (or Georgian Friendship Highway) to the border village of Verkhniy Lars (Upper Lars). We were just 30 minutes' drive from Georgia and just under 250 kilometers from Keti's home city of Tbilisi, capital of Georgia.

The Georgian Military Highway is one of two major main road crossings from Russia to Georgia; the other being the Transkam which travels from western North Ossetia-Alania through the Roki Tunnel and into South Ossetia. The Military Highway, although shorter in distance takes considerably longer in time, due to border processing and also frequent rockslides through the pass. Both roads originate in North Ossetia-Alania's capital city of Vladikavkaz.

People have used the Georgian Military Road route since antiquity; a traditional pass through the Caucasus Mountains for invaders as well as traders. Since the building of the alternative Transkam route by Soviet Russia in 1988, the Georgian Military Road diminished in importance, with the road being totally closed by Russia in 2006, presumably because of tensions building up to the Russo-Georgian War of 2008. The road was re-opened in 2013 following requests of neighbouring Armenia and since has become once again an important transport artery, mainly for large trailer trucks linking Russia and Armenia.

Verkhniy Lars was a typical border village. Straddling the main highway, the tiny village comprised numerous small shops selling food and provisions, cafes, small hotels, petrol and motor service stations and curiously a huge number of outlets selling Georgian motor vehicle insurance. Apparently, a vehicle must carry Georgian insurance before it is allowed passage across the border. And having seen the manic driving habits of some of the North Caucasian men, it was not surprising.

Ahead of us were queues of large trucks, lined up and stationary. The processing at land borders anywhere in the world is always a nightmare. But we heard that the Verkhniy Lars border was out there on its own when it came to bureaucracy. At the time, I thought how good it would be to cross the border and meet up with Keti and Vano in Tbilisi. Sadly, it was merely a fanciful dream.

Toward Staraya Saniba Tracts and Karmadon: Site of the Horrific 2002 Kolka Glacier Avalanche.

Our trip took us from the Georgian border north, and then west toward Staraya Saniba Tracts and the former township of Karmadon in the high Caucasus Mountains.

The scenery was simply gorgeous; alpine meadows loaded with luxuriant grasses, brimming with wildflowers and grazed by fat black cattle. Rounding a hairpin corner of the snaking Karmadon Road, we would be treated to rows of brilliantly coloured beehives. Surrounding us were semi-forested, rolling conical hills leading to the mighty snow-capped massifs of the Greater Caucasus. Here we were not far from Mount Kazbek, an extinct volcanic giant and the highest peak in North Ossetia.

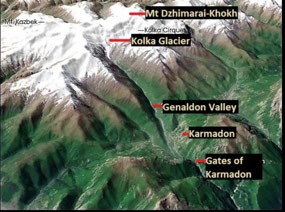

The higher we climbed, the less vegetation we encountered; forested slopes making way to short tufted grasslands and signs of major landslides and erosion. It was not far from here that a massive glacial avalanche occurred following the collapse of the Kolka Glacier on the evening of 20th September 2002, totally engulfing several of the local settlements. In places the glacial flow was over 130 meters in depth. And more than 125 people, including a whole film crew lost their lives in the incident.

NASA Earth Observatory explains:

"In a cirque just west of Mt Kazbek, chunks of rocks and hanging ice on the north face of Mount Dzhimari-Khokh tumbled onto the glacier below. Kolka shattered, setting off a massive avalanche of ice, snow and rocks that poured into the Karmadon Depression, a small bowl of land between two mountain ridges, and swallowing (village of) Nizhniy (Lower) Karmadon and several settlements. At the northern end of the depression, the churning mass of debris reached a choke point: the Gates of Karmadon, the narrow entrance to a steep walled gorge.... The debris swept through the Genaldon River Valley.... acting as a dam, creating several lakes upstream. "

It is thought the avalanche was most likely caused by a combination of seismic activity and consecutive warmer years causing the ice within the glacier to melt, hence destabilising its structure. Another theory is that the explosives used as sound effects in the movie making triggered the avalanche flow. Or perhaps it was a combination of the two?

Staraya Saniba Tracts

As we began to descend down to the Cauldon River, we caught site of a tiny village nestled in the foothills. It was Staraya Saniba (Old Saniba). And it was the prettiest entrance to this delightful settlement.

At an altitude of some 1,400 meters Saniba is home to just under 200 people. The name literally means "Trinity" and comprises two villages of Wallah (Upper) and Dallas (Lower) Saniba Tracts. Saniba, unlike some of its neighbouring villages was spared the destruction by the Kolka Glacier avalanche.

The village which dates back to ancient Alanian times, is home to the (modern) Church of the Holy Trinity and to an ancient burial ground with traditional Ossetian crypts and numerous old leaning tombstones.

The first church which was thought to have been built in the 12th century in honour of the Holy Trinity, was destroyed during the invasion of the Mongol-Tatars. It later was rebuilt at the end of the 18th century. The second church also had a miserable fate, being destroyed by the Soviets in the 19th century. The new church was built less than twenty years ago when people re-built it at their own expense.

There was no doubt about this charming little village. It certainly had an air of prosperity. A number of very new looking buildings adorned its paved streets, including cafes, a guest house and some very lovely sculptured gardens. Overlooking the opposite side of the river was a Great Patriotic War Memorial and a very fine bronze memorial sculpture of a sorrowful woman holding what appeared to be a soldier's coat.

It was hard not to notice just how many World War II memorials there were in Russia. And no wonder, when it is estimated the country lost a staggering 26 million citizens, including some 11 million soldiers.

A group of workers doing some very attractive paving work of the footpaths stopped to talk with us. The friendly men told us they were from Azerbaijan and that the new village renovations were of Turkish design. They were keen to chat with us, giving the impression they didn't see too many tourists here. And certainly, none from Australia.

It all had a very tourist-oriented look to it, and we could not help but wonder who was footing the finance for the works. But set in the loveliest valley and not far from the world famous Dargavs ancient crypts or "The City of the Dead", it could well be an excellent tourist base. Here is a video courtesy of Abdullah: https://youtu.be/K-J41WsCz4E

Sad Karmadon

Just twenty minutes' drive west took us to Karmadon, site of the avalanche path which killed an entire film crew who became trapped in the valley.

Such a beautiful setting, it exuded a sad yet tranquil atmosphere. At the entrance to the gorge was a lonely memorial to Sergei Bodrov, a well known Russian actor who was part of the film crew. A metal photograph of the young man is inscribed "If a person has to die, then the ones who love him will not stop loving him". Sergei Bodrov would have been no older than thirty years of age.

Not far away was another memorial. This was to the more than 50 film crew who lost their lives at the site. The Russians do their memorials well. A bronze sculpture of a mournful woman in a flowing shawl was accompanied by a simple marble plaque detailing the names of those who died. The translation of the inscription reads something like "We stay without you. But you will stay with us". It was very moving.

The scenery at Karmadon, like most of this region was sublime: wild towering mountains and divine rolling lush meadows. Not far away we could see grazing cattle and some very fine looking horses, including a number of mares with new born foals. I am not just a cat tragic. Having owned horses nearly all my life I am an equine tragic too. And I was totally captivated by a young colt with a long white rear stocking and several white body markings, a dead give away to his obvious paint horse genes.

It was no wonder the animals were all in such great condition. The alpine pasture was almost knee high. On first glimpse it was all so pristine, so picturesque and so totally unspoilt. And best of all, there was not a soul to be seen.

But it was not totally untouched. Up on a hill overlooking the valley was a deserted township; a number of substantial, four storey cement buildings just left to rot. Ugly, decaying and windowless, these blacked eyed dungeons presented a lonely scar on an otherwise untouched environment. We had seen so much of this sort of abandoned settlements, particularly in Far East Russia. But this was the first we had seen in the North Caucasus.

We were not sure of the background to the township. Someone obviously had grand plans for a settlement as most of these buildings looked to be apartment style blocks with splendid views over a steep escarpment bank to the distant far mountains. Was the township abandoned during the Soviet collapse, when Russia was literally on her knees from poverty and famine? Or was it because of inept Soviet management?

Like a contemporary sculpture gone horribly wrong, these buildings exuded yet another sort of sadness; a confronting out door museum of a not so distant past.

A light braying brought me back to reality. A group of donkeys were doing their best to attract our attention. Snowy muzzled and very pretty, the seemingly friendly donkeys did their best to see if we had any treats for them. And on finding we had none, like spoilt children they flattened their ears, shook their heads and marched away.

The Ghostly Necropolis of Dargavs - "Anyone Who Visits This City Will Not Come Out Alive...."

It was a tortuous but scenically breathtaking trip from Karmadon to Dargavs. The narrow road took a huge detour north up and around the Kolka Glacier remains, zig zagging along a steep escarpment before descending onto the world renown Dargavs Necropolis or "City of the Dead". Only just 8.2 kilometers from Karmadon, the trip took us over twenty minutes.

Our first glimpse of the necropolis was spell binding. Huddled against a lonely hillside was what on initial appearance looked like a cluster of small white cottages, was actually a small "city" of some 99 individual ridge curved crypts. Some were small with a peaked top, others were several stories high and looked more like miniature watch towers. This was the ancient Dargavs Necropolis.

The grave site which follows the Tabildon River for some 17 kilometers is thought to date as far back as the 12th century. The walls were made from local stone blocks and mortared with a thick binding of lime-clay. All those buried there were accompanied by their possessions; the ancient Ossetians believing they were essential for the after life. On a higher point a little further down the valley was a watch tower, built to watch over and guard the dead.

Otherwise known as The City of the Dead, legend says that if anyone tried to get into the necropolis site, they would never emerge alive....

And for this there was a very sound reason. In the 18th century, when a plague swept through Ossetia, the clans built quarantine houses for sick and dying members of their family. They were provided with food but up until their death, were not allowed the freedom to leave. People who did not have family to bury them, would just wait in the cemetery until their death; a horrible and lonely way to go.

There sure was a creepy feeling to this eerie City of the Dead. And it wasn't just our imaginations running riot. Interestingly, in 2018 a Moscow-based film company was forced to drop all plans to shoot a horror thriller at the site because a regional official reportedly terrified by the script, refused to allow the firm to film the movie.

We spent some time meandering around the crypts at our leisure. It was one of the wonderful luxuries of the little tourist travelled North Caucasus.

There were no lines of coaches, no tourists and no fences. We could just wander without having to pay any fees nor adhere to any pathways. The crypts were in splendid order with no signs of vandalism or graffiti. Peering into some of the crypts, we saw the bones of the ancient dead as they were left and hopefully at peace; eerie but tranquil.

"Sun Valley"- Fiagdon

Our travels took us slightly south-west from Dargavs down the mountainous road toward the village of Fiagdon. Terraced foothills dotted with small farm cottages surrounded our journey. The scenery was really glorious.

Not far along the road we noticed a small bust and memorial to Soviet leader Josef Stalin. Apparently, Stalin is still revered as a great leader in parts of North Ossetia. There is even a belief that he was born in North-Ossetia, and not in Gori, Georgia as widely accepted.

And soon we were in the small rural village of Fiagdon right on the fast flowing Fiagdon River. The area is apparently now known by the rather touristy name of "Sun Valley" or "Sun Dale". And no doubt the region has enormous tourist potential; a very scenic part of the world with a fascinating history and fabulous sites.

To our left was Khidikus Monastery, an imposing grey stone building with huge arches and impressive turrets. A long staircase adorned with stone religious sculptures led from its gates. Did we want to visit, asked Abdullah? No, us heathens were more interested in lunch. Alan, trying to make up for our poor history appreciation did however explain that he was raised in a Catholic boarding school and had absolutely no desire to visit a monastery ever again. Our Muslim Abdullah seemed to understand; even was relieved I think.

Lunch was at the most lovely restaurant. A very new looking local stone building, it was surrounded by expansive beautifully sculptured gardens with delightful fountains and ponds. Someone obviously saw some tourist potential here. And the food was excellent too. After a long morning, it was very good to sit, relax and enjoy our meal of a variety of vegetable salads to which we were rapidly becoming addicted. We agreed, we could not ask for a much better way to spend the day.

Dzivgis Fortress

Our final visit for the day was to the Dzivgis Fortress, north of Fiagdon and on our way to Vladikavkaz.

The Dzivgis Fortress is one of the largest natural rock fortresses in the Caucasus, standing right on the slopes of a rocky ridge behind Dzivgis village. Faultlessly camouflaged, the ancient fortress is literally built right into the ridge. And it is almost impossible at first glance to identify; just a series of small blank windows peering at their enemy over the valley. A perfect defensive retreat.

Dating back from the 13th to the 16th centuries, the fortress complex comprises seven independent defensive facilities that are located right next to natural cave formations. The communication between the separate fortress towers was by way of bridges or wooden walkways laid on beams that were hammered into the rock crevices. When the walkways were removed, the towers were almost impossible to raid. The central tower was built above the entrance to a long cave, about 70 meters from the entrance.

This powerful fortress repeatedly saved the Ossetians during the raids of the conquerors. One Oriental chronicler wrote interestingly: "It was extremely difficult to get there (to the fortress) due to the height, which was so great that our eyes would get blurry and our hats would fall back from our heads".

Early sources mention the Dzivgis Rock Fortress as being one a series of "impregnable fortresses" associated with Tamerlane's bloody campaign in the 15th century.

It is also thought that in the 17th century Shah Abbas the Great, after capturing most of Georgia, made an expedition through the Caucasus, invading the territory of present day North Ossetia-Alania. Here he tried unsuccessfully to capture three fortresses; the Dzivigis Fortress being the first.

The fortress was yet another fantastic historical site. And again in pristine order. There is certainly great potential for tourism in this region. We were just very fortunate we thought, to have seen it in its purity.

To Vladikavkav

Late in the afternoon we headed north-east on the forty minute drive to the capital city of Vladikavkaz. And here we walked into our very beautiful plush Alexandrovsky Grand Hotel.

We were now on another planet; the eclectic city of Vladikavkaz in the modern world North Ossetia-Alania.

Gorod Vladikavkaz, North Ossetia–Alania, Russian Federation

Gorod Vladikavkaz, North Ossetia–Alania, Russian Federation

Aert

2019-10-15

You are certainly covering a lot of ground

Geoff Nattrass

2019-10-18

You guys so lucky to see these places as they now stand and before any great tourist influx (if it happens) - love the high maintenance of tourist hotels, very Soviet :-)