MESTIA VILLAGE

It was not the most relaxing of nights. The single beds were uncomfortable and a group of young medical students staying in the guest house kept us awake for some time into the early hours of the morning. I guess we could not blame them. The walls were not exactly well insulated and after all, we have been guilty in our younger days of doing the very same thing, only probably much worse. And these young people were not even drinking! My morning shower was icy cold and so Alan decided to stay in bed a bit longer, in hope that the hot water may improve with use. In fact it did, only once it warmed up the shower rose kept falling off its stand onto the floor which began to flood with water. Hearing Alan's justifiable curses on a very cold morning, I decided to take an early morning stroll before breakfast.

The first sluggish rays of dawn yawned over the shrouded mountains. Mestia was still asleep; only a few cows and their calves wandered down the lonely main street. In the distance dogs barked a bored chorus. The brisk mountain air was invigorating and after a short walk I veered off the the main street to the right crossing a substantial bridge over the gushing snow fed torrents of the Mestiachala River. Wandering through the surrounding flower strewn alpine valley meadows, flanked by the just illuminated snow capped mountains and those strange haunting watch towers, it was easy to lose myself in the solitude of the glorious mountain dawn. Familiar sounds of cow bells distracted me. A farmer and his son were herding a small group of cattle down one of the lane ways and onto the surrounding pastures, every third or so senior cow having a bell around her neck; their calves loping playfully behind. The farmer raised his staff in greeting. The young boy scowled and walked by. Life seemed frozen in time in Mestia.

By the time I walked back to our guest house, Mestia village was bathed in brilliant sunshine, absorbing the dawn but only just awake. A baker's shop was opening its doors and a few farmers herded their cows down the main street to the nearby pastures, urging them on with gentle taps of their staffs. Several friendly marshrutka (mini van) drivers approached me asking if I wanted a lift to Zugdidi or to the capital city of Tbilisi. It seemed there was plenty of transport if I had needed it. A German tourist asked me if I knew where the Information Office was. He had flown in the evening before and was staying with a family home stay out of the village. A backpacker, he was delighted with the extremely low cost of his flight* and the welcoming family with whom he was staying. Mestia had a nice feel.

It wasn't always like that. Until about ten years ago, the region was apparently not considered at all safe with frequent armed robbers targeting tourists. The matter was settled abruptly in 2004 when Georgian police shot and killed the chief robbery baron and jailed the rest of his thuggish friends.

Now it was light I was able to take in more of Mestia and its surrounds. A tidy little village at an elevation of 1,500 meters, Mestia comprises basically one main street and sort of a town square lined with numerous chalet like houses, some wooden with rather charming cross timbered balconies whilst others resembled neglected fibro boxes. Despite Mestia's rather biblical outer appearance, there were some signs of a tourism effort in the main street with an Information Centre, numerous guest houses and a fairly new looking stone fortress-like Mestia Hotel. A number of general stores sold a wide variety of goods and food, and most importantly beer and wine. I thought about buying some bread for our travels but decided against trying to struggle with my lack of Georgian language. Later I was to find that many of the locals were fluent in English, Russian, Georgian as well as their native Svan dialect.

*From Wikitravel: A new airport in Mestia - Queen Tamar Airport - has opened, and flights between Mestia and Tbilisi are now available 5 times a week for an amazingly cheap 65 lari or US $27 (including transfer to Tbilisi if flying from Mestia) each way.

Breakfast was basic but the lovely staff made sure that we had the first seating and had plenty to eat. The dishes comprised hard boiled eggs, large bowls of sour cottage type cheese, bread and very nice homemade local berry jams. We asked Keti if this was a typical Georgian breakfast. She affirmed, saying she thought it was a very good array of food and that she particularly liked the curd cheese. We love discovering what people from other countries eat, and for some reason thought that the Georgians who looked for all intents and purposes just like us or other Europeans, would have similar eating preferences. However, when we told Keti that we normally would eat fruit first for breakfast followed by bread or toast, she was quite incredulous saying that she would never dream of eating fruit first thing in the day. While a full bowl of sour curd cheese for breakfast was not to our liking, it was a real reminder of how different - even in just simple eating habits - such seemingly alike looking cultures can be.

TO USHGULI - IPARI AND KALA DISTRICTS

Our itinerary for the day included a few hours in Mestia followed by a long drive south-east through the neighbouring mountain villages to Ushguli in the high country near the Russian border. Although the journey was only 47 kilometers, the hazardous narrow mountains road much of which was unsealed, would mean the trip would take us over three hours. We had read widely about the secluded Ushguli, whose roads are open mainly during the short summer season. We were hoping it would be our Tusheti experience. And I think it was.

As Vano drove, Keti chatted to us about the fascinating history of Mestia, Ushguli and the Svaneti region.

By the 1st century BC, the Svan people of the Svaneti region, thought to be descendants of Sumerian slaves, had forged a reputation as fierce warriors and gate keepers of the high mountain passes. Greek geographer Strabo documented their ferociousness in his early writings, noting also that the tribes used sheepskins to sift for river gold, fueling popular speculation that Svaneti may have been the source of the famous Golden Fleece sought by Jason and the Argonauts. The Svan culture was deeply embedded by the time Christianity arrived to the region around the 6th century, with its own language, complex codes of chivalry, "life for a life" blood revenge and communal justice.

Georgia being part of the Caucasus and true frontier between Europe and Asia over the following centuries, fell victim to the rampaging armies of the powerful empires of the Arabs, Mongols, Ottomans, and Persians. The Svaneti region however managed to retain the sliver of land amongst the gorges of the Greater Caucasus and remained unconquered until Russia exerted control in the mid-19th century. During these tumultuous times of war, lowland Georgians sent icons, jewels and manuscripts to the mountain churches and towers for safe keeping, making Svaneti a true repository of ancient Georgian culture.

It is interesting that whilst the Svans are deeply religious Christians, they still hold fast to their Middle Ages traditions of singing, mourning and celebrating - and fiercely defending family honour. In fact today, Svaneti is still a living ethnographic museum.

We were completely intrigued by the numerous defense or watch towers around Mestia and Ushguli. Built between the 9th and the 12th centuries, they offered protection for families against local as well as foreign enemies, and natural disasters. The towers functioned as family living quarters, fortresses of defence and personal treasuries. They offered protection to the owners, to their livestock and as vaults for the most valuable family possessions, holy scriptures and icons.

When we thought about it, the numerous towers made perfect sense. In these rugged environments, the villages were too scattered to be encircled by protective walls and so each individual house had to be separately fortified against invading armies. Today, most of the towers stand in almost perfect condition, looming formidably over their eerie land; silent witness of centuries of turbulent history of a very strange place.

The drive out of Mestia toward the villages of Mulakhi, Ipari and Kala en route to Ushguli, followed the Enguri River, transversing pretty verdant alpine pastures, dotted with farm houses, watch towers and meadows of flowering apples and pears. In the distance was the magnificent twin peaked Mount Ushba at an elevation of 4,710 meters.

On our way, Keti chatted about religion in Georgia and the all powerful St George, the protector of their country and also patron saint of Britain as well as acknowledged and celebrated on special St George Days by a staggering host of other nations including Canada, Croatia, Portugal, Cyprus, Greece, Georgia, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the Republic of Macedonia..

I must confess that I didn't know a lot about St George, only that he was revered as a saint and had at some stage apparently slain a dragon - which sounded a bit unusual. Apparently St George was born to Christian parents in 270 AD in Cappadocia (now Eastern Turkey). He then moved to Palestine where he became a Roman soldier, but later resigned protesting against his pagan leader the Emperor Diocletian, who had led the persecution of Christians in Rome. St George's rebellion led to his imprisonment and torture. Bravely, he refused to abandon his faith and was eventually dragged through the streets and beheaded on 23 April 303 AD. It is now considered that the legend of the dragon slain by St George was - not surprisingly inanimate - but a representation of the devil to whom local people (some sources say Beirut, others the town of Selene in Libya) sacrificed young women to appease the beast. When St George killed "the dragon", saving the lovely Cleolinda, a princess to be and next victim of sacrifice, the local people in their gratitude converted to Christianity. Following the Crusades some hundreds of years later, St George was to be regarded as a protector with soldiers wearing his signature red and white cross into battle. Today, the lovely Georgian flag depicts St George's red and white cross.

It is pretty well accepted that there are two things you really shouldn't discuss with good friends. One is politics, the other religion. The same advice would arguably apply to travel guides and their clients. Keti was a devoutly religious young woman, whose strength of faith was truly admirable. She also had studied history and religion, and was undertaking post graduate studies in art history, particularly as it applied to old churches. And she knew what she was talking about....

During our conversation about religion and St George, Keti talked earnestly about the heart breaking persecution of the Christians throughout history. Until then Alan and I had been totally non-committal about our religious convictions but caught off guard, I casually commented that Christians had also committed their share of persecution. After all, remember the Crusades? Keti was obviously quite taken aback. "Do you believe in God?" she asked, her large grey eyes widened like saucers. "Nooooo, we are aethiests" I replied slowly and carefully (note the long "nooo" was hopefully to avoid being rude - and well, you never know we may sometime wish to change our minds). To her credit, Keti did not directly reply but kept chatting on about Georgian history and religion.

Our first stop on our journey was at a most exquisite old church in the village of Nakipari in the Ipari District, a valley inhabited since the 9th century. The Nakipari Church of St George dates back to 10th century, although its interior paintings belong to the 11th century. It sits nestled in an overgrown garden surrounded by numerous graves, the more recent bearing headstones with very clear photo portraits of the deceased. We had not ever witnessed this type of headstone before but it was truly effective. Walking through the graveyard, we felt almost familiar with the strange audience of headstones watching our every move.

Keti, whispered there was a service being held but the priest was happy for us foreigners to sit in. One thing I had learnt so far in Georgia was that it is not only advisable but essential for women to carry two scarves; one to cover your head, the other your backside. Usually but not always, churches will supply shawls to provide for the latter.

I will never forget the impact this church service had on me. And neither will Alan. The priest quietly beckoned us into a dimly lit, tiny stone chamber filled with the pungent scent and thick smoke of incense. While one (presumably junior) priest gave the holy liturgy, the senior priest guided and assisted him. On the left of the church stood three local peasant women; their ethereal singing in exquisite harmony. A local elderly disabled woman was the only other member of the congregation. Unlike the others present, she was allowed to remain seated.

I could not keep my eyes off the three women singing. They looked old for their young years, dressed in simple worn cotton dresses and shawls; plain frayed scarves securing their long brown hair. The women were totally absorbed with the sermon and their responsive singing. I don't think they would have even known of our presense.

What we were witnessing could have well been a snapshot in time of some 200 years ago. We were spell bound, mesmerised by the eerie chanting of the priests, the haunting choral singing of the women and the evocative ambiance of the tiny medieval chapel. We must have stayed for nearly an hour. Perhaps time, just like in Mestia village ceased to exist. Or maybe it had never existed? And like the sombre ever present watch towers, we found ourselves being silent witnesses in a very strange place....

For some time during our journey toward Ushguli, we were quite speechless from our "out of body" church experience. I wrestled with my athiesm. Perhaps I should in the future regard myself as agnostic? And I think I saw Keti smile with satisfaction. It was one heck of a way to make a point, we thought.

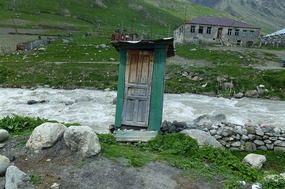

Our next destination was the short trip to the village of Khe, some 20 kilometers south-west of Mestia. On our way we stopped briefly at a gorgeous little watch tower known as "The Tower of Love" seated right beside the gushing torrents of the Enguri River. According to legend, a very long time ago a young man and woman living in the two different local villages of the Enguri River fell in love. As village elders would not consent to their marriage, they made this tower their house on the river bank. It is said that the residents of this village, the Bogreshi Village - Ipari people are their descendants. A typical fairy tale but I am unable to find out whether they did in fact live happily ever after.

Khe was a curious, if rather forlorn old village on the banks of the Enguri River. Two storey, corrugated iron roofed farm houses built from local slate, stone or timber housed timber verandahs, some ornately carved in the old Georgian style; others were in a sad state of disrepair. There were no main streets, just unsealed passageways between the jumble of tumbling houses. Chickens, goats and sheep wandered through the clutter of the village walk ways.

As Keti led us on a wander around Khe, there was not a soul to be seen and at first it seemed as if no-one had ever lived in this forgotten little village. Or perhaps like us, the local people disliked visitors, let alone tourists disturbing the vast solitude of the valley. It was all quite mysterious and not at all difficult to imagine you were in yet another capsule in time.

Loud excited greetings suddenly flooded out from one of the older premises, shaking us abruptly into reality. A woman and her elderly mother had recognised Keti and shuffled down from their house to warmly embrace her. More of the family joined in, smiling at us and shaking hands. The older woman was a close friend of Keti's grandmother and the two had not seen each other for many years. There was much hugging and kissing, and despite our language barrier, we were made as welcome to the village as Keti. There was no doubt about our Keti, she was a very warm and caring young woman and her rapport with the two women was rather lovely.

The village was fascinating, as was the 13th century Church of St Barbares, a small one nave structure with basilica type architecture. The sad little church looked almost as lonely as the village, snuggled in overgrown grass and weeds, and rather neglected looking grave stones which again bore the portraits of the deceased. On one gravestone - which appealed to us - was placed two bottles of what appeared to be local wine. The church was locked but apparently, the inside is adorned with richly decorated frescoes dating back to the 13th century. Recently restored the wall paintings and icons display Christ, the Mother of God, apostles and other saints which have been venerated by the Svans over many centuries.

Vano was an excellent driver. And where it was safe to do so he drove fast. On this trip however, he was very steady and extremely careful. The road from Khe to Ushguli was unsealed and in places very difficult but nothing as treacherous as those we had witnessed in countries such as northern Pakistan, Ladakh and parts of Tibet. Some parts of the road were good, other parts transversed washways from the mountainous slopes with no guard rails with huge drops to the Enguri River. On the left hand side of our road towered the mountains of Tetnuldi, the 10th highest peak in the Caucasus at an elevation of 4,858 meters and Shkhara, the third highest at 5,193 meters. During winter the road can be closed from Kala to Ushguli for days due to snow and ice.

THE MEDIEVAL VILLAGE OF USHGULI

Well, if we thought that Mestia and its surrounding villages were old and secluded, then Ushguli was truly medieval; a time warp of an ancient era with age old traditions and practices still in place.

Ushguli translates as "Fearless Heart" and there are stories told of residents' ancestors who so fiercely protected their land that they murdered one of the royal lords who tried to invade and take over the Ushguli community.

On a cloudy and stormy day, the drive along the Enguri River and into Ushguli was breathtaking. Nestled under the massive Mount Shkhara and its extraordinary glacier, the village is home to more than 20 watch towers dating back to the Middle Ages and is a UNESCO Heritage Listed Site. Even though it is snow covered for six months of the year, Ushguli houses the highest permanently inhabited communities in Europe. At an elevation of 2,200 meters, it comprises four separate but very close villages of Chvibiani, Murqmeli, Zhibiani and Chazhashi. We had witnessed much higher villages, especially in Pakistan but unlike Ushguli, they were deserted in the winter seasons when farm workers or nomads moved to lower grounds.

All up there are about 70 residences housing around 200 people - much the same size as our own tiny home village of Crowdy Head on the Mid North Coast of New South Wales, Australia. A small school operates year round. An Ethnological Museum is housed in one of the watch towers and close by is the famous Lamaria Chapel (Church of the Mother of God), dating back to the 10th and 12th centuries, and according to some sources, where Queen Tamar was buried. Once an important religious centre of Upper Svaneti, the church has been restored and is still the main church used for celebrating the liturgy.

The church was unfortunately closed for the day and despite concerted efforts by Keti and two other German tourists, we were unable to gain entry. To Alan's disappointment however the Ethnological Museum was open. For someone measuring Alan's some two meters in height, crawling up the almost vertical watch tower stairs was a nightmare. It was worse on the way down as the stair well is only very, very tiny meaning you can't stand up let alone climb easily down the treacherous stair cases. The museum did however house a very fine collection of gold, silver and wooden icons and crosses dating back to the 12th century. And the view from the top of the tower was fantastic; sombre watch towers majestically over sighting their village, the surrounding brilliant green alpine pastures and those formidable mountain peaks.

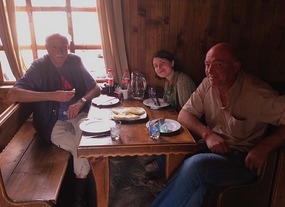

We were ravenous and were delighted when Keti suggested that we stop and have a break at a tiny cafe in Chazhashi. We were quite taken with Georgian kajapuri*, the buttery fresh cheese stuffed bread, and ordered it for a snack before we left Ushguli for the long trip to Mestia. The cafe owners were real purists and must have made the bread from scratch as it took almost an hour before it was served. But it was truly delicious. A jug of beer would have been nice but Vano was driving and Keti didn't drink and so we settled for Coca Cola - which is of course much worse for you.

**I must confess that I have not yet had a try at making kajapuri but this recipe appealed to me and had the thumbs up from Keti! The link is: http://thecolourofpomegranates.blogspot.com.au/2011/03/masterclass-from-mimino-in-khajapuri.html

Rolling blue-black cumulus nimbus clouds signaled a massive storm looming over the mountains. Vano was concerned about the drive which Keti said could become really dangerous if we had torrential rain. If the wash ways across the unsealed part of the road flooded, it could also mean we may be stranded in Ushguli for the night. To be perfectly honest, I would not have minded at all staying longer in this strange but fascinating mountain village.... However, it did not eventuate.

Our trip home was long but happy. Not surprisingly, religion was not mentioned! Keti had certainly made her point.

We arrived in Mestia in the early evening. Workers at our Chubu Guest House had been constructing a stone fence on the grounds and chatted to us as we arrived back. It looked like back breaking work but its appearance was truly lovely and very much in tune with the Mestia environs. On a warm balmy evening, we invited Keti and Vano to join us for a drink on our verandah overlooking Mestia village. Keti, to our surprise accepted a whisky and water while Alan and Vano drank beer. It was the sort of relaxing evening you really appreciate and we remember it as one of the nicer, yet very simple occasions of our Georgian travels.

.

Silent Witnesses of a Strange Place

Friday, May 22, 2015

Ushguli, Georgia

Ushguli, Georgia

Other Entries

-

4To Moscow - Two Contrasting Faces of Russia

May 1012 days prior Moscow, Russian Federationphoto_camera5videocam 0comment 0

Moscow, Russian Federationphoto_camera5videocam 0comment 0 -

5Russian History Time Line Summary

May 1012 days prior Moscow, Russian Federationphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 0

Moscow, Russian Federationphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 0 -

6A Walk with Svetlana - Absorbing Moscow City

May 1111 days prior Moscow, Russian Federationphoto_camera42videocam 0comment 0

Moscow, Russian Federationphoto_camera42videocam 0comment 0 -

7We Get Hopelessly Lost in Moscow...

May 1210 days prior Moscow, Russian Federationphoto_camera13videocam 0comment 0

Moscow, Russian Federationphoto_camera13videocam 0comment 0 -

8Aboard the Sapsan: From Moscow to St Petersburg

May 139 days prior St. Petersburg, Russian Federationphoto_camera18videocam 0comment 0

St. Petersburg, Russian Federationphoto_camera18videocam 0comment 0 -

9A Walk With Nadya: Absorbing St Petersburg

May 148 days prior St Petersburg, Russian Federationphoto_camera34videocam 0comment 1

St Petersburg, Russian Federationphoto_camera34videocam 0comment 1 -

10State Hermitage Museum & Adventures in St Petes

May 157 days prior St. Petersburg, Russian Federationphoto_camera22videocam 0comment 1

St. Petersburg, Russian Federationphoto_camera22videocam 0comment 1 -

11Once We Had No Armenian Visas - Now We Have Four..

May 166 days prior Yerevan, Armeniaphoto_camera5videocam 0comment 0

Yerevan, Armeniaphoto_camera5videocam 0comment 0 -

12The Caucausus - An Uncomfortable Dinner Party

May 175 days prior Yerevan, Armeniaphoto_camera4videocam 0comment 2

Yerevan, Armeniaphoto_camera4videocam 0comment 2 -

13The Caucasus - A Historic Timelime Summary

May 175 days prior Yerevan, Armeniaphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0

Yerevan, Armeniaphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0 -

14Armenia: Proud People of a Lost Land

May 175 days prior Yerevan, Armeniaphoto_camera25videocam 0comment 0

Yerevan, Armeniaphoto_camera25videocam 0comment 0 -

15Under the Gaze of Noah

May 184 days prior Yerevan, Armeniaphoto_camera36videocam 0comment 2

Yerevan, Armeniaphoto_camera36videocam 0comment 2 -

16Lake Sevan - The Tranquility and The Terror

May 193 days prior Gyumri, Armeniaphoto_camera36videocam 0comment 0

Gyumri, Armeniaphoto_camera36videocam 0comment 0 -

17Gyumri: God Will Heal Your Wounded Soil

May 202 days prior Bavra, Armeniaphoto_camera18videocam 0comment 0

Bavra, Armeniaphoto_camera18videocam 0comment 0 -

18Keti, Vano & Welcome to Georgian Hospitality....

May 202 days prior Akhaltsikhe, Georgiaphoto_camera19videocam 0comment 0

Akhaltsikhe, Georgiaphoto_camera19videocam 0comment 0 -

19To Borjomi - Playground of the Tsars

May 211 day prior Batumi, Georgiaphoto_camera25videocam 0comment 1

Batumi, Georgiaphoto_camera25videocam 0comment 1 -

20Batumi to Zugdidi - Mestia: Guests of the Dadianis

May 22earlier that day Mestia, Georgiaphoto_camera27videocam 0comment 3

Mestia, Georgiaphoto_camera27videocam 0comment 3 -

21Silent Witnesses of a Strange Place

May 22 Ushguli, Georgiaphoto_camera46videocam 0comment 0

Ushguli, Georgiaphoto_camera46videocam 0comment 0 -

22Kutaisi: "This is My Abode Forever and Ever..."

May 242 days later Kutaisi, Georgiaphoto_camera26videocam 0comment 0

Kutaisi, Georgiaphoto_camera26videocam 0comment 0 -

23To Gori: Birth Place of Joseph Stalin

May 253 days later Gori, Georgiaphoto_camera25videocam 0comment 0

Gori, Georgiaphoto_camera25videocam 0comment 0 -

24Gori to Tbilisi: Travelling Through Troubled Lands

May 253 days later Tblisi, Georgiaphoto_camera27videocam 0comment 0

Tblisi, Georgiaphoto_camera27videocam 0comment 0 -

25In the Presense of St Nino & Vano's Perfect Picnic

May 264 days later Tbilisi, Georgiaphoto_camera19videocam 0comment 0

Tbilisi, Georgiaphoto_camera19videocam 0comment 0 -

26In Fields of Gold: Davit Gareja Monastery Complex

May 275 days later Davit Gareja, Georgiaphoto_camera21videocam 0comment 0

Davit Gareja, Georgiaphoto_camera21videocam 0comment 0 -

27Bodbe Monastry: Resting Place of St Nino

May 286 days later Sighnaghi, Georgiaphoto_camera18videocam 0comment 0

Sighnaghi, Georgiaphoto_camera18videocam 0comment 0 -

28From Georgia Into Azerbaijan - "Good Luck"!

May 286 days later Sheki, Azerbaijanphoto_camera26videocam 0comment 0

Sheki, Azerbaijanphoto_camera26videocam 0comment 0 -

29Azerbaijan - A Very Well Kept Secret....

May 286 days later Sheki, Azerbaijanphoto_camera24videocam 0comment 4

Sheki, Azerbaijanphoto_camera24videocam 0comment 4 -

30Along the Dagestan Border to Ancient Lahij Village

May 297 days later Lahıj, Azerbaijanphoto_camera49videocam 0comment 0

Lahıj, Azerbaijanphoto_camera49videocam 0comment 0 -

31Baku - One of the Beautiful Cities of the World

May 308 days later Baku, Azerbaijanphoto_camera60videocam 0comment 0

Baku, Azerbaijanphoto_camera60videocam 0comment 0 -

32Flight Chaos OR a Saviour Called Mikhail

May 308 days later Baku, Azerbaijanphoto_camera7videocam 0comment 1

Baku, Azerbaijanphoto_camera7videocam 0comment 1 -

33Three Russian Miners AND The Bride of Frankenstein

May 319 days later Shanghai, Chinaphoto_camera6videocam 0comment 0

Shanghai, Chinaphoto_camera6videocam 0comment 0 -

34Shanghai OR How To Stuff a Dooner Into a Suit Case

May 319 days later Shanghai, Chinaphoto_camera5videocam 0comment 0

Shanghai, Chinaphoto_camera5videocam 0comment 0 -

35"Madam, This Queue is for Business Class Only...."

Jun 0110 days later Shanghai, Chinaphoto_camera7videocam 0comment 0

Shanghai, Chinaphoto_camera7videocam 0comment 0 -

36Reflections & Those Who Made Our Trip So Speci

Jun 0312 days later Sydney, Australiaphoto_camera12videocam 0comment 0

Sydney, Australiaphoto_camera12videocam 0comment 0

Ushguli, Georgia

Ushguli, Georgia

2025-05-22