The Road to Xiahe

After we woke the speedboat driver up on the way back from the Bingling Si caves and monastery, we were dropped off at a sloping car ramp slick with water

. The car ferry had just departed leaving a strong wake of waves in its path and this caused our little tub to bounce around like a cork.

Our now wide-awake boat driver kept jumping up from the cockpit to the bow to try to jump onto the ramp to let us get off. But every time he got to the front of the boat he had to run back through the tiny doorway hatch to realign the boat so it wouldn't crash into the ramp. We were stuck inside the enclosed swaying bathtub unable to help and watching with just a touch of alarm as he ran back and forth.

After several tries he finally managed to jump ashore with a rope and then waved us to attempt the same from the still tossing boat. Landing on the slippery surface with our backpacks and camera bag was not quite what we had signed up for, but we had no choice. I went first and grabbed for Carolann as she thankfully landed right side up.

Meanwhile, our car driver, who had crossed the lake on the ferry, stood by the car watching the frantic to and fro of the boat driver and our efforts to leap ashore with indifference. He obviously didn't want to get his feet wet. (I've noticed that all Chinese drivers wear shiny black leather shoes.)

We waved good bye to the boat and waited by the car while our "chauffer" went to water some nearby weeds. And then we set off for the second stage of our two-day journey into the mountains south of Lanzhou towards Xiahe and the monastery at Labrang Si

.

We leave the lake and climb into the sandy mountains again, but this time on the south side of the reservoir. We quickly ascend a series of long switchbacks to the summit and drive along its sandy razor edge. All along the ridge are Muslim villages with men in black garb and round white hats tending flocks of sheep and goats.

The steep hills are terraced all the way down to a dry river bed miles below and men are plowing under the stubble from the just harvested crops into the sandy brown earth. Some are using donkeys, some are pulling the plows themselves. It's time to put the fields to bed.

The road is occasionally blocked by convoys of those funny three-wheeled tractor carts seen everywhere in China. They're loaded high with potatoes on their way to the nearest big "city". And the roadside is lined with piles and piles of them. As we drive along behind the carts, potatoes fall off the cart and pelt our car like brown snowballs until we honk and dart around them, narrowly missing heavily laden donkey carts coming out of dirty little side lanes

.

Our driver has to slow frequently as women in black veils throw grain and corn stalks right in our path. They're using cars to soften up the thresh for animal feed. In some places both lanes are completely covered with slippery looking mounds of green or brown vegetation. Our driver courageously plows right through without slowing down, but honking all the way.

We come to a plateau and descend to a city. Suddenly we're in a scene right out of the middle east, as the tall minarets of several sparkling mosques appear and the streets are chock full of Muslim men in white hats. Nobody is working, they're all out on the street haggling for goods. Sheep carcasses hang in open-air butcher shops and corn and potatoes are piled high in the streets beside white-striped sunflower seeds spread out to dry in the sun. It’s hard to believe that we’re still in China!

We stop at an ancient mosque that was partially destroyed by the Chinese during the Cultural Revolution but is now mostly rebuilt

. The entranceway walls are lined with stone murals of incredibly intricate hand carved scenes detailing rural life. Oddly, the older mosques like this one are built more like Chinese Buddhist temples with intricate woodwork, tiled porticos and pagoda-style roofs. There are no minarets.

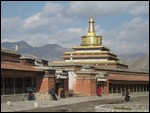

Scenes of Muslim village life like this continue for two solid hours until the landscape suddenly changes to higher mountains with slopes verdant with evergreens. The housing also morphs from red-brown mud brick into colourful Tibetan style log houses, with Yaks in the yard instead of donkeys. The minarets are replaced by white Tibetan Buddhist Stuppas and prayer cloths can be seen waving in the breeze atop the peaks.

The highway is brand new. So new in fact that workers are still painting the lines -- without warning signs or cones -- forcing us to swerve to avoid them and the oncoming traffic. On the new bridges piles of rock and gravel block one lane alerting drivers to big gaps in the concrete where they have just finished installing the expansion joints in wet concrete

. Thank God it’s still daylight so we can see these tiny piles in time. At each bridge we engage in a game of Tibetan chicken with oncoming traffic and do a quick zig zag around the piles at either end of the bridge.

Even with the new highway, we're barely doing 70 kph. It's not just the donkeys, yaks and construction, 70 is the legal speed limit on a highway that would be 90 kph back home.

And then it all comes to a screeching halt. Up ahead we spy a long line of tour buses, cars and trucks. They're all waiting to enter a tunnel through one of the mountains. We don't know if there's been an accident or just more construction.

But we're very lucky. A policeman directs the tour bus ahead of us onto a rough dirt track and motions for us to follow. Our driver doesn't fully understand, but follows anyway and we bounce and scrape around the mountain for 15 minutes along an old donkey track and through a small village until we come to a complete halt on the other side.

Sadly there's a new lineup of buses and cars within frustrating sight of the new highway as it exits the mountain tunnel. The bridge on the old road has been piled high with construction debris to prevent vehicles from crossing. Several drivers are scrapping at it with their hands and throwing boulders under tires trying vainly to get their vehicles over the mounds of debris

.

Our driver despairs. I get out to take some pictures and Carolann goes back to sleep in the back seat. We each deal with setbacks in our own way on this trip. As each vehicle ahead of us inches over the piles, our car gets closer to its chance to scrape its bottom on the rocks and our driver looks more and more concerned. But with Carol and I both out of the car, it gains enough clearance to creep cautiously over the rocks and we're off again.

By now it’s dark and we start to worry about more rock piles, not to mention hitting a Yak that weighs as much as a full grown Moose back home. Luckily we've only an hour to get to Xiahe, our destination, and we pull into this tiny frontier town in time to find the "best" hotel in town, a rundown three star that has somehow lost one of its stars with the passage of time. It's freezing up here in the mountains, and this place -- advertised as one of the few with hot water and heat -- has not yet decided to turn on the heat

.

An extra comforter helps us get through the night, but shivering. In the morning we wear our winter coats to breakfast and warm our hands over the hot tea glasses and hot boiled eggs that have become our standard breakfast fare on this trip.

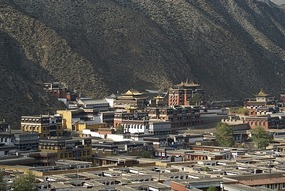

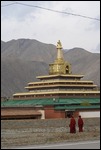

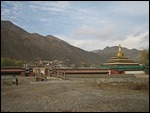

The next morning we drive to a hill overlooking the Labrang Monastery, the purpose of our visit to Xiahe. This is the most important Tibetan monastery outside of Tibet and well worth the visit. It's a major pilgrimage site for Buddhists from China and even Tibet itself.

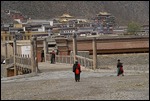

It's a big as a small city, spread out along the flank of a mountain that is now hidden in the morning mist. We climb the hill on foot to take pictures, dodging the steaming piles of Yak poop, and the cows and donkeys that seem intent on pushing us off the hill. Carolann has never had much luck with donkeys.

It starts to snow and my hands are frozen from taking pictures

. The sky is grey and not very good for photos so we decide to head on down to explore the monastery from ground level.

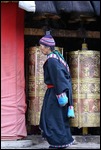

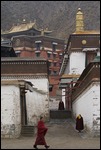

We cross the river on an old wooden bridge passing women dressed in traditional Tibetan sheepskin coats "kowtowing" their way to the temple. They clasp their palms together in front of them, bend at the waist and then slide their hands and knees on the ground completely prostrating themselves. Their hands and knees are covered with the soles of shoes or pieces of worn leather for protection. Some of them have done this for miles and miles in a pilgrimage to the monastery. I've seen this on TV, but it is incredibly moving to witness their devotion in real life.

Others are kissing the posts of the bridge or the outer walls of the monastery itself. The entire perimeter of the "city" is constructed of a low wall with a porch that is lined with brightly coloured Tibetan prayer wheels. A steady procession of pilgrims and monks in flowing purple robes marches along this porch turning each wheel and chanting as they proceed. The line moves clockwise, and only clockwise we are reminded, around the monastery.

Inside we visit six different temples with figures of Buddha. Each has been constructed at a different time by a leader in a "previous life" the first as far back as 1708 by the "first-generation Living Buddha". Upon the death of each Living Buddha a new one is born taking his place in an endless series of reincarnations

. The current Living Buddha here is third in line after the Dalai Lama.

The monastery itself was partially destroyed and closed during the Cultural Revolution, its 3,600 monks scattered and persecuted. It wasn't reopened until 1980 and many of the temples have been rebuilt, but only 1,200 monks or lamas remain. There are six colleges of higher learning here: Astronomy, Esoteric Buddhism, Law, Medicine and Theology (higher and lower). On the hillside are several small white huts where monks can go to meditate in isolation. Normally they live in small mud-brick dwellings throughout the monastery grounds.

The sky has cleared up and the sun is bright when we approach the main prayer temple, the largest building on site. We can hear the drone-like chanting of 700 monks inside and we enter slowly with reverence.

We're suddenly thrown into pitch black darkness and we can't see anything but vague shapes kneeling on the ground and swaying

. The air is thick with the sweet smell of incense cut by the sour smell of Yak-butter candles. Gradually our eyes adjust to the gloom with only the dim candles to guide our way around a large hall, three-storeys high with huge wooden columns holding up a high unseen ceiling. Large red banners hang down almost to where the 700 monks sit kneeling and chanting, reciting their sutras or prayers.

They are bareheaded and barefoot even though it is quite cold. We walk around the large room clockwise in awed silence. The monk who is our guide points out intricately carved and brightly coloured montages of Buddha made entirely of Yak butter. These are five-feet high and wide and include beautifully crafted animals listening to Buddha surrounded by bright flowers with hundreds of tiny butter petals. Even more amazing is that they are now 10-months old. They are created each at the Tibetan New Year and then destroyed the next year.

The chanting suddenly stops and young barefoot novice monks rush in from the cold with Yak-butter tea, yoghurt and ground reddish barley

. The monks pour the tea over the barley, roll it around in their bowls with their hands and then form a reddish brown roll that they eat.

Suddenly a gong sounds and with a whirl of flowing red capes all the monks dash headlong outside and sit on the steps in rows with their bright yellow rooster cowls on their heads. They chant a few prayers and at the sound of another gong they all rush like a red tide back inside for more prayers and a second course.

This has to be the most amazing sight I have seen in our entire four weeks of travel in China. The chanting and gongs were mesmerizing and deeply moving. The devotion of the pilgrims and hundreds of monks was overwhelmingly surreal. No tour group could experience this, the atmosphere and emotions would be ruined. Traveling on our own is difficult, but I would not have missed this moment for the world.

Xiahe and Labrang Si Monastery

Sunday, January 30, 2011

Bingling Si to Xahe, Gansu, China

Bingling Si to Xahe, Gansu, China

Other Entries

-

1Our Approach to Traveling

Sep 21131 days prior Toronto, Canadaphoto_camera0videocam 0comment 0

Toronto, Canadaphoto_camera0videocam 0comment 0 -

2Our first Chinese Wedding

Sep 26126 days prior Shenzhen, Chinaphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 3

Shenzhen, Chinaphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 3 -

3From Eden to Hell's Gate

Sep 30122 days prior Guiyang, Chinaphoto_camera5videocam 0comment 0

Guiyang, Chinaphoto_camera5videocam 0comment 0 -

4Kunming, City of Eternal Spring

Oct 01121 days prior Kunming, Chinaphoto_camera4videocam 0comment 1

Kunming, Chinaphoto_camera4videocam 0comment 1 -

5The Honeymoon is over

Oct 06116 days prior Lijiang, Chinaphoto_camera19videocam 0comment 0

Lijiang, Chinaphoto_camera19videocam 0comment 0 -

6The Value of Hello

Oct 13109 days prior Lijiang, Chinaphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 2

Lijiang, Chinaphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 2 -

7Stuck in Pingyao isn't so bad

Jan 1119 days prior Pingyao, Chinaphoto_camera15videocam 0comment 0

Pingyao, Chinaphoto_camera15videocam 0comment 0 -

8Not so Spicy Chengdu (by Carolann)

Jan 1218 days prior Chengdu, Chinaphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0

Chengdu, Chinaphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0 -

9Sichuan Province -- Chengdu (by Carolann)

Jan 1218 days prior Chengdu, Chinaphoto_camera7videocam 0comment 0

Chengdu, Chinaphoto_camera7videocam 0comment 0 -

10Lanzhou -- the eagle is flying again

Jan 1317 days prior Lanzhou, Chinaphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 0

Lanzhou, Chinaphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 0 -

11Wedding Day in Lanzhou Brings back Fond Memories

Jan 246 days prior Lanzhou, Chinaphoto_camera5videocam 0comment 0

Lanzhou, Chinaphoto_camera5videocam 0comment 0 -

12Bingling Si Temple and Rock Carvings

Jan 30earlier that day Bingling Si, Chinaphoto_camera13videocam 0comment 0

Bingling Si, Chinaphoto_camera13videocam 0comment 0 -

13Xiahe and Labrang Si Monastery

Jan 30 Bingling Si to Xahe, Chinaphoto_camera24videocam 0comment 0

Bingling Si to Xahe, Chinaphoto_camera24videocam 0comment 0 -

14Happy New Year from China!

Feb 1415 days later Beijing, Chinaphoto_camera20videocam 0comment 0

Beijing, Chinaphoto_camera20videocam 0comment 0

Bingling Si to Xahe, Gansu, China

Bingling Si to Xahe, Gansu, China

2025-05-22