When a guide who wants to be hired tells you he can take you a traditional ceremony that "hardly ever happens," you have to be skeptical. You ask yourself, Really?? Of all possible scenarios, this rare ceremony is happening ON THE VERY DAY we happen to be in Bajawa?

As it turns out, this time, the answer was yes

. We've never hired a guide before – we like the flexibility of choosing our own destinations and schedule. But Shen got a good feeling from Alfons, and I felt ready to let someone else handle the logistics. Independence is great, but it’s also a big fat hassle. For once, I liked the sound of, “Meet here at eight and I’ll take care of the rest.”

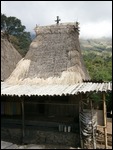

In the morning, we went to two villages near Bajawa, and Alfons gave us the cultural run-down. The villages are nestled on the flanks of Gunung Inerie, the largest volcano in Flores. As with the villages in Sumba, the homes encircle ancestral tombs. Houses in “modern” villages are also arranged in this manner, but the tombs are tile instead of stone. The traditional villages also have shrines to the ancestors; for the males, they build carved poles with conical roofs, and for the females they build what look like small houses. There is one male and one female shrine for each clan that lives in the village. Flores is nominally Catholic, but animist traditions are strong

. In order to get a national ID card, Indonesians must declare their religion, and it must be among the six “approved” religions. Unsurprisingly, “animism” and “ancestor worship” do not appear on the list. The result is a blend of Catholic and animist traditions, symbols, and beliefs throughout the islands.

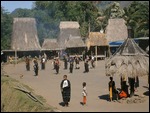

After a quick lunch, we began the two-hour hike to the ceremony. A French-Canadian couple joined us with Alfons, and we joined a caravan of about 20 villagers. We could hear the ceremony before we could see it. There was drumming, and a hollow metallic clanking that sounded like rhythmic wind chimes. We approached the village from above, and as we followed the trail down we saw clouds of dust billowing from below the feet of slow-moving dancers. Hundreds of people sat in front of the houses, completely encircling them. The women had tied strings to their fingers with bird feathers tied every few inches; the men brandished swords. They made subtle gestures, turning up toward the sun and down toward the ground, tracing wide arcs in the dust across the courtyard

. Most of the dancers were adults, but some groups of children appeared to be in training.

We walked to a house at the far end and sat inside on the floor. Women were shuttling bamboo baskets of rice and meat to everyone inside (and, as we later learned, to everyone outside as well). We drank tea and ate a heaping pile of white rice. Things were hectic in the house, but we got a little info on the ceremony.

We were essentially at a massive housewarming party. When a new house is built in the village, they hold a blessing of sorts for the new house. The village hosts it, providing meals to everyone who comes. The dancers are all from the host village. The ceremony goes on for two days, and people come from all the surrounding villages. The ceremony is the biggest cost in building a house, and people often have to save for it. This ceremony was for a house that was built a year ago. But the ceremony must take place.

After our meal, we went outside with everyone else to watch the dancers

. Everyone was so welcoming, making room for us on the porches and making sure we had been fed. Everything was going so well...until the pig sacrifices. The first day of the ceremony is for dancing, and the second is for animal sacrifice, but apparently the lines are not clearly drawn. We had been told that 5 buffalo and 30 pigs would be sacrificed the next day, and their horns and jawbones would adorn the front of the new house. The bigger the family, the more sacrifices must be made. The animals are brought from surrounding villages as gifts to the host village, and they’re used to feed the guests on the second day. As Shen pointed out (in his always-analytical way), it’s a good means of wealth distribution among the villages. Only the wealthy can afford to bring animals, but everyone gets to eat.

It was difficult to witness. They didn’t make a spectacle out of it, and I didn’t watch, but from the sounds it was clearly a long and painful death. Shen took a look, and the primary means of killing was a machete to the brain

. Once the pigs were dead, twenty men sat in a circle and butchered every last piece of them. Shen was surprised that I wasn’t completely traumatized, given my particular fondness for pigs. In no way do I want to defend macheteing pigs to death, but it’s not worse than what pigs endure in the US (and in fact, the lives of pigs here are much better). Any time I see pork on the menu at home, I’m well aware that this is the suffering that produces it. Witnessing it does not make it more real. If I flipped out every time I knew a pig had died a horrible death, I would be flipped out most of the time. Again, I’m not defending it – I don’t believe that “cultural tradition” justifies cruelty any more than “convenience and taste” justifies it at home. If animals are the only high-quality protein available (a rare scenario), there are ways to virtually eliminate the suffering of the process. Suffering is shitty, whether it’s a sacrifice for a new house or a morning slice of bacon.

Well! That’s enough about that. Despite the difficulties of the day, we felt very lucky to have wound up in that situation. We were shocked to be the only foreigners there, and grateful to Alfons for taking us. It was one of those special moments that you hope for when you depart on your grand adventure, but that you can never guarantee.

Housewarming, Flores-Style

Saturday, July 02, 2011

Bajawa, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia

Bajawa, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia

Other Entries

-

1Arrival

May 2835 days prior Nusa Lembongan, Indonesiaphoto_camera19videocam 0comment 3

Nusa Lembongan, Indonesiaphoto_camera19videocam 0comment 3 -

2Exploring the Nusa

May 3033 days prior Nusa Lembongan, Indonesiaphoto_camera15videocam 0comment 3

Nusa Lembongan, Indonesiaphoto_camera15videocam 0comment 3 -

3Kami belajar Bahasa Indonesia!

Jun 0329 days prior Seminyak, Indonesiaphoto_camera18videocam 0comment 3

Seminyak, Indonesiaphoto_camera18videocam 0comment 3 -

4New Friends

Jun 0626 days prior Seminyak and Lovina, Indonesiaphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 4

Seminyak and Lovina, Indonesiaphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 4 -

5Good time to go

Jun 1022 days prior Seminyak, Indonesiaphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0

Seminyak, Indonesiaphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0 -

6Ubud

Jun 1517 days prior Ubud, Indonesiaphoto_camera41videocam 0comment 0

Ubud, Indonesiaphoto_camera41videocam 0comment 0 -

7Bali-Bye

Jun 1715 days prior Denpasar, Indonesiaphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 8

Denpasar, Indonesiaphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 8 -

8The Wild East

Jun 1913 days prior Waingapu and Pulupanjang, Indonesiaphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 2

Waingapu and Pulupanjang, Indonesiaphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 2 -

9Surf Camp

Jun 239 days prior Kallala, Indonesiaphoto_camera17videocam 0comment 6

Kallala, Indonesiaphoto_camera17videocam 0comment 6 -

10Skipping through the village

Jun 266 days prior Waikabubak, Indonesiaphoto_camera24videocam 0comment 0

Waikabubak, Indonesiaphoto_camera24videocam 0comment 0 -

11Interminable Ferries and Magical Lakes

Jun 302 days prior Moni, Indonesiaphoto_camera34videocam 0comment 0

Moni, Indonesiaphoto_camera34videocam 0comment 0 -

12Housewarming, Flores-Style

Jul 02 Bajawa, Indonesiaphoto_camera48videocam 0comment 1

Bajawa, Indonesiaphoto_camera48videocam 0comment 1 -

13Komodo Part I: Land

Jul 075 days later Labuanbajo, Indonesiaphoto_camera26videocam 0comment 2

Labuanbajo, Indonesiaphoto_camera26videocam 0comment 2 -

14Komodo Part II: Sea

Jul 075 days later Labuanbajo, Indonesiaphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0

Labuanbajo, Indonesiaphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0 -

15Not in Kansas

Jul 119 days later Jakarta, Indonesiaphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 2

Jakarta, Indonesiaphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 2 -

16Surf Extravaganza - Shen's Guest Post!

Jul 1816 days later Batu Karas, Indonesiaphoto_camera27videocam 0comment 7

Batu Karas, Indonesiaphoto_camera27videocam 0comment 7 -

17The Joys of Travel

Jul 1917 days later Yogyakarta, Indonesiaphoto_camera1videocam 0comment 3

Yogyakarta, Indonesiaphoto_camera1videocam 0comment 3 -

18Path to Enlightenment (or at least better grammar)

Jul 2220 days later Borobudur, Indonesiaphoto_camera39videocam 0comment 5

Borobudur, Indonesiaphoto_camera39videocam 0comment 5 -

19Visa Run

Jul 2321 days later Singapore, Singaporephoto_camera7videocam 0comment 1

Singapore, Singaporephoto_camera7videocam 0comment 1 -

20River Cruising

Jul 2725 days later Pangkalan Bun, Indonesiaphoto_camera49videocam 0comment 3

Pangkalan Bun, Indonesiaphoto_camera49videocam 0comment 3 -

21Into the Wild

Aug 0332 days later Kutai National Park, Indonesiaphoto_camera32videocam 0comment 5

Kutai National Park, Indonesiaphoto_camera32videocam 0comment 5 -

22Surf Safari - SHEN GUEST POST #2!!!

Aug 1039 days later Kuta, Indonesiaphoto_camera34videocam 0comment 2

Kuta, Indonesiaphoto_camera34videocam 0comment 2 -

23Honeymooning At Last

Aug 1443 days later Gili Meno, Indonesiaphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 3

Gili Meno, Indonesiaphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 3 -

24Happy Postscript

Aug 1645 days later Washington DC, United Statesphoto_camera4videocam 0comment 4

Washington DC, United Statesphoto_camera4videocam 0comment 4

Bajawa, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia

Bajawa, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia

2025-05-22