Dawn awoke and Chitral Town was alive with people, trucks, jeeps, motor bikes and noise. Men in long elegant shalwar kameez, men with woollen Pashtun hats, long bearded men in flowing gowns with pill box caps and men in waist coated jerkins walked purposely along the dusty Chitral streets. There were no women to be seen.

Our PTDC hotel was very centrally located and gave us great views of down town Chitral. After a quiet night, awoken only by the local cats' and dogs' mating calls, we were ready to explore the much anticipated nearby valleys of Birir and Bomburet, the home of the elusive Kalash people.

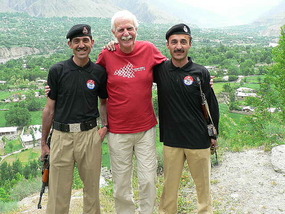

This day our escorting police guards were dressed in full military attire, now openly equipped with their impressive large Kalashnikov rifles. The guards undertook their role with admirable seriousness. They were delightful guys and although they joked, laughed and chatted with us in perfect English, they never left our sides. If one of us walked off to take a photo or to admire a particular view, then one of the police guards was silently at our side. Right at our side... I often joked with Alan that it was impossible to even slip away for a quiet fart, without a police guard shadowing us. Their attention was impressive. It was hard not to conclude that someone must have thought this place was dangerous.

That morning Alan was sitting in the front seat of the jeep, his long legs would have taken up far too much of our precious space in the back seat which housed Sadruddin, me and the two police officers, the four of us sitting in a sort of "V" arrangement. As we started off on our jeep journey, Alan yawned contentedly and leant back on what he thought was the head rest of the seat. I had to remind him that it was in fact the muzzle of one of the Kalashnikovs. Alan typically asked the guards if they had them locked. "Yes, sir" they assured him. Did they get much practice in using the rifles? Yes, they did. Were they good shots? "Yes, sir - very good shots". They assured him also that their rifles were deadly accurate up to a distance of 300 meters. But I'm sure I detected an almost imperceptible smile on their faces.

Driving out of Chitral Town we looked down at the striking scenery of verdant valleys and an intensively farmed landscape nestled along the Karun River. Silver roofed farmhouses dotted green pastures, heavily cropped fields and fruit orchards; all rimmed by the beautiful huge peaks of the Hindu Kush.

A rugged, spine jarring ride through death defying roads took us toward the isolated Birir Valley, about twenty kilometers south-west of Chitral along the Kunar River gorge. The one vehicle width, rocky jeep mountain roads were familiar to us. They clung impossibly to near vertical mountain slopes, intersected by rock slides, alluvial fans and deeply eroded water courses. At one stage when the track just disappeared under a landslide, Sardar's jeep actually waded up and through one of the stream beds. Whilst none of the roads were anything as nerve wracking - as in height above the gorges - as the infamous Shimshal Road we travelled on during our trip of 2009, they were nevertheless treacherous. As Alan said so re-reassuringly, you don't need to be one kilometer above a gorge to get killed if the jeep went over the edge; just a couple of hundred meters drop would do the job quite nicely.

Unlike a lot of northern Pakistan with its arid and treeless mountains, the Birir Valley was densely wooded. Moist forests of oaks, cedar and conifers, including deodars and junipers lined the mountain roads and fiercely gushing snow fed streams. Steady rain began to fall creating an almost mystical atmosphere and a most fitting introduction to the first of the three Kalasha Valleys we were to visit. In the pretty, misty morning light you could even begin to believe in the Kalasha "Mountain Fairies".

Birir Valley, like the other Kalasha Valleys, is not a single township as such but rather a series of successive villages. Located at an altitude of some 2,300 meters, Birir is regarded as the most traditional of the Kalasha locations. Solid wooden, stone and mud houses are built on top of each other, clinging precariously to the steep mountain slopes.

Our first glimpse of the Kalasha was a couple of startlingly beautifully dressed women walking in front of our jeep. Dressed in heavy black robes, richly embroidered with brilliant thread and wearing the traditional "shashut" head dress with its long heavily beaded hanging panel and adorned with reams of flaming orange and yellow necklaces, the women bore a proud and confident air. It was really quite breathtaking to take in our first sighting of a people we had read so much about. And then to our delight we passed through the first of a string of villages, the houses simply lit up with the brilliant colours of the Kalasha women's' clothing. Vibrant pinks, greens, turquoises, oranges and reds contrasted fantastically against their heavy black robes. Children played happily, oblivious of our jeep and of the intense work being performed by the Kalasha women.

Sardar stopped the jeep near some exposed wooden coffins located right on the road side. The dead are "buried" in the coffins fully clothed and with all their jewellery. It was once tradition to leave the coffins of the dead exposed above the ground but in more recent years, lootings of the coffins has put an end to this ancient practice.

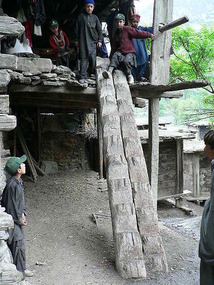

The Kalasha owner of a local guest house and his family welcomed us into their home and generously invited us to join them for lunch. The mostly wooden guest house was built on raised beams accessed by unbelievably steep "stairs", or rather two adjoining wooden poles with grooves etched into them. While the local children ran up and down the "stairway" with gay abandon, it was somewhat of a comical sight watching us clumsily clambering up and crawling down on our back sides. Two women dressed in traditional Kalasha clothing were preparing lunch over a charcoal stove on the floor of one of the rooms, a simple meal of what appeared to be rice and bread. The rooms were dark and basic and seating was provided by very short legged wooden stools. The guest house owner was very friendly, self educated and spoke excellent English. Like most Kalasha men, he wore a shalwar kameez with a jerkin styled waistcoat and what we would describe as a woollen Pashtun-style hat. He explained about life in the valley and the changes to the Kalasha people largely brought about by the more recent access by the jeep road to Chitral Town. Most concerning to most Kalasha people we spoke with was the erosion of their culture and the conversion of many young Kalasha people to Islam.

Life for the Kalasha people in this still extremely isolated valley is tough. It was cold inside the houses we visited that day, even though it was nearly summer. With average temperatures of around 2 degrees C and the jeep road cut off by snow, winters must be frightful. Kalasha houses are generally grouped against the steep valley sides and are mostly one-room structures with a fireplace in the middle and beds on short platforms around the walls. A sacred area dedicated to Jeshtak, the female divine who the Kalasha believe is the guardian of all family matters, is located between the fireplace and the front wall, and must not be stepped upon by women. Water to most of the houses must be carried in from nearby rivers or channels and heating is by way of the central fireplace. More recently, chimneys have been installed above the fireplaces to reduce the smoke and associated respiratory disorders caused by continual smoke inhalation. In most instances there are no special facilities for toilets or bathing. Most houses include store houses for grain and dried fruit, and sheds nearby for cows and sheep. The sacred goats are kept above the villages in special stables.

The Kalasha people of Birir, as in the other two valleys are largely subsistence farmers with income supplemented by selling basic handmade Kalasha craft items such as the beaded Shashut head dresses, necklaces etc. The use of money is a relatively new phenomenon and introduced largely as the result of the jeep road access to the valleys which has allowed the people to purchase commercial goods from nearby Chitral. Traditionally the Kalasha existence was non-monetary and based on a voluntary mutual co-operation between the household, clan and the community.

The basic field crops are maize, wheat and beans, and the vegetable crops are mainly tomatoes, potatoes and pumpkins. Fruit trees comprise mulberries, apricots, apples and walnuts. Grapes are used to make wine for the frequent festivals. Milk is preserved as cheese and clarified butter.

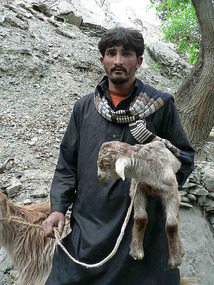

Raising animals is central to daily life in Birir, and the other Kalash Valleys, Goats and cows provide daily sustenance of meat and milk, as well as wool, hair and leather. The poor goats, considered as "pure" animals are particularly "honoured" as sacred animals and used regularly as sacrifices for religious ceremonies.

The dilemma for the Kalasha people reminded us very much of our experiences during our visit to the Shimshal Valley in the Northern Areas in 2009. Whilst the jeep road access was changing and probably eroding the traditional culture of the people, by our "outsider standards" it was undeniably improving the health, education and general welfare of the local people. Again, the main concern with local people was the loss of their culture and the influence that Muslim dominated education was having on the younger Kalasha people.

Low chanting moans and strange sad wailing indicated a funeral was taking place at one of the Kalasha houses in Birir. Apparently, a very old woman had died during the last few days and the funeral ceremony was taking place in her family home. The last thing we wanted to do was to intrude or disturb such personal moments, but the dead woman's family on seeing us warmly beckoned us into the room where the old woman's body laid. We did not enter the funeral room but watched from what we hoped was a respectful distance. During the funeral process, the women maintain vigil, singing a sad lamenting dirge and waving their hands back and forth over the dead body. The female relatives do not wear head coverings and undo their braids as a sign of respect and mourning. On our way out of the village we walked past a number of distressed women, their tasseled and unbraided hair drawn over tearful faces.

We were quite taken that as total outsiders witnessing a very personal event, we were still made welcome by the Kalasha people. In the villages we visited, we found the Kalasha people to be initially private and somewhat shy, but when we met with them they were quietly friendly and welcoming.

Over lunch Sadruddin was delighted to hear from a tour guide for a group of Japanese tourists that at our next destination of the villages of the Bomburet Valley, the local Kalasha people were performing a dancing and singing festival. We were not quite so enthusiastic as we really dislike contrived "cultural performances" particularly those organised specially for tourists. During the last evening at Chitral we had met with several of the Japanese tourists and their Japanese and Pakistani guides. In a country where we generally meet few if any tourists, we were surprised but very pleased to meet up with the Japan tour and even more surprised that they comprised twelve women and just one man. Even more amazing was that they were accompanied by NINE police guards! We did not ever ask, but we did sometimes wonder who was paying for the police....

Bomburet is the most developed of the Kalasha Valleys. At nearly every turn of the jeep road, hand painted signs indicated the presense of a hotel or guest house. We were told by locals that a lot of the hotels are now run by Muslim people, once again a sad lament that possible valuable income for the local peoples was being siphoned into the hands of non-Kalasha "outsiders".

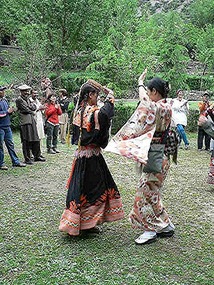

Loud rhythmical drumming, repetitive chanting songs, vibrating stomping of feet and a splendid display of women's dancing and vibrantly coloured festive dress greeted us at our arrival to Bomburet. Groups of happy young women held each other four at a time, arm to waist, in wild circular dancing. Older women danced individually or with another woman. A handsome distinctively featured Kalasha man in a long brown shalwar kameez appeared to be the leader of the drumming and dancing ceremony. Assisted by younger men also drumming frantically, he encouraged the young women to come forward and dance, and then keep dancing. The frantic whirling and dancing appeared to place the young women in almost a trance like mode.

The interesting part was that the festivities did not appear to be intended as a tourist activity. In fact the dancers and onlookers seemed quite oblivious of our presense and of the Japanese group with their numerous police guards. Kalasha people, young and old, were concentrating on their dancing and singing, laughing and clapping as the dancing became faster and wilder.

Everyone seemed to be thoroughly enjoying the festivities and indeed it was hard not to get excited about it all ourselves. A Japanese woman, wearing a traditional beautiful pink and cream kimono must have thought the same and joined in the fun, dancing enthusiastically with the locals. It was a wonderful but admittedly totally incongruous sight, two peoples from completely different backgrounds and cultures dancing together in their traditional dress. There was no need for verbal communication. Their excited and joyous faces said it all. The ground was wet and muddy from the morning rain and we could not help but fear for the beautiful kimono and pretty white clog shoes. And then the Japanese guide and more of her tourists joined in. Even the police seemed to be enjoying themselves, smiling and chatting with the tour group and patiently looking at their photos taken from their mobile phones. And even the Kalasha women had mobile phones. It was all a lot of fun, if rather quite bizarre.

Alan and I love Japanese people. We have spent quite some time in Japan, both in our working and retired lives and adore both the country and the people. As a race they seem such an enigma. On one hand they are so very polite, super regimented and sometimes to us overly conscious of protocol, but on the other hand they can be - even by our standards - absolutely outrageous. For us, it is this unpredictable spontaneity that makes them such wonderful, warm and fun people to be with. The tourists certainly were in an outrageous mood this afternoon.

The festivities finally ended and an exhausted looking Kalasha-Japanese dance crew flopped back on the muddy grass.

We spent the rest of the afternoon wandering around the village. Two well dressed government officials wearing immaculate cream shalwar kameez were visiting one of the houses and stopped to talk with us. They explained in great detail how committed the government was to looking after the welfare of the Kalasha people and preserving their customs and culture. They were very pleasant men and we enjoyed our chance meeting with them. We hoped that they were right but we had the distinct impression that we were seeing the last of a fragile yet fascinating race.

We enjoyed exploring the small craft shops which were run out of individual homes. I really did not need a shashut head dress, especially one that weighed over a kilo. But we bought it because we wanted to contribute a small amount to the local Kalasha people. The shashut was beautiful, embroidered in red, orange and black tones and ornately decorated with numerous cowrie shells. We were intrigued with how the Kalasha people would find cowrie shells. Sadruddin informed us that they come from Karachi on the southern coast of Pakistan. We supposed that they must buy them in. Amazing.

We framed the shashut with some traditional Kalasha-made orange beads when we arrived back home in Australia and it now sits in pride of place in our living room. We cannot tell you how many people comment on its beauty. It is very special to us and a wonderful reminder of our visit to the Kalash Valleys.

We stayed that night at the Bomburet PTDC Hotel. The attractive hotel was situated in a very pretty location, the staff was friendly and the food was great. It was such a relief to be eating good food again. I am a real "curry-o-phile" and thoroughly enjoyed the delicious Pakistani biryanis, curries, freshly made dhal and chapattis. We spent some time talking with the Japanese group before they retired early. Inclement weather had prevented them from flying back to Islamabad the day before and they were understandably anxious about their anticipated very early flight the next morning. We were anxious about them too as there was talk from the guides about travelling back by road through the highly dangerous Dir and Swat Valley areas. We sincerely hoped that our Japanese friends' flight would be confirmed for the next morning.

We slept very soundly that night. Our police guards, did not have the same luxury. They patrolled our hotel grounds all through the night and had no sleep at all.

A Four-Seater Jeep, Six People & Two Kalashnikovs

Thursday, May 05, 2011

Bomburet, North West Frontier Province, Pakistan

Bomburet, North West Frontier Province, Pakistan

Other Entries

-

11Around Mashad - Mausoleums of Two Literary Giants

Apr 1916 days prior Tehran, Iranphoto_camera7videocam 0comment 0

Tehran, Iranphoto_camera7videocam 0comment 0 -

12Tehran to Hamadan - So Dizi My Head is Spinning...

Apr 2015 days prior Hamadan, Iranphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0

Hamadan, Iranphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0 -

13To Khorramabad: Connecting With the Archaemenids

Apr 2114 days prior Khorramabad, Iranphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0

Khorramabad, Iranphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0 -

14"If You Were Israeli - I Cut Your Throat!"

Apr 2213 days prior Ahvaz, Iranphoto_camera7videocam 0comment 0

Ahvaz, Iranphoto_camera7videocam 0comment 0 -

15Iran-Iraq War Martyrs: Flying the Fallen

Apr 2312 days prior Shiraz, Iranphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0

Shiraz, Iranphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0 -

16Perceptions of Persepolis: Grandeur of the Ruins

Apr 2411 days prior Shiraz, Iranphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0

Shiraz, Iranphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0 -

17Photo Gallery of Persepolis and Naqsh-E Rostam

Apr 2411 days prior Shiraz, Iranphoto_camera16videocam 0comment 0

Shiraz, Iranphoto_camera16videocam 0comment 0 -

18Today: The First Day of the Remainder of Your Life

Apr 2510 days prior Kerman, Iranphoto_camera16videocam 0comment 0

Kerman, Iranphoto_camera16videocam 0comment 0 -

19Yazd - Such a Lovely Place, Such a Lovely Place...

Apr 278 days prior Yazd, Iranphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 0

Yazd, Iranphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 0 -

20Toward Esfahan - "The Jewel of Ancient Persia"

Apr 287 days prior Esfahan, Iranphoto_camera34videocam 0comment 0

Esfahan, Iranphoto_camera34videocam 0comment 0 -

21A Gorgeous Carpet, Jolfa and Fascinating Abyaneh

Apr 305 days prior Abyaneh, Iranphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 0

Abyaneh, Iranphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 0 -

22Photo Gallery of Abyaneh Village

Apr 305 days prior Abyaneh, Iranphoto_camera13videocam 0comment 0

Abyaneh, Iranphoto_camera13videocam 0comment 0 -

23Destination Tehran - Reflections on our Travels

May 014 days prior Tehran, Iranphoto_camera13videocam 0comment 0

Tehran, Iranphoto_camera13videocam 0comment 0 -

24Osama bin Laden Dead - Our Travel Plans in Chaos

May 023 days prior Dubai, United Arab Emirates, United Arab Emiratesphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0

Dubai, United Arab Emirates, United Arab Emiratesphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0 -

25For Better or For Worse - We Head off to Islamabad

May 032 days prior Islamabad, Pakistanphoto_camera4videocam 0comment 0

Islamabad, Pakistanphoto_camera4videocam 0comment 0 -

26Eclectic Chitral - North West Frontier Province

May 041 day prior Chitral, Pakistanphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 0

Chitral, Pakistanphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 0 -

27The Wonderful Faces of Chitral Town

May 041 day prior Chitral, Pakistanphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0

Chitral, Pakistanphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0 -

28A Four-Seater Jeep, Six People & Two Kalashnikovs

May 05 Bomburet, Pakistanphoto_camera15videocam 0comment 1

Bomburet, Pakistanphoto_camera15videocam 0comment 1 -

29Love Affair with Rumbur, A Sick Jeep Trip to Buni

May 061 day later Buni, Pakistanphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 0

Buni, Pakistanphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 0 -

30Insight into the Life of the Lost Kalasha People

May 061 day later Buni, Pakistanphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 3

Buni, Pakistanphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 3 -

31More Photos of the Kalasha Peoples

May 061 day later Buni, Pakistanphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 0

Buni, Pakistanphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 0 -

32Tandoori Chicken, Potatoes & Eggs at Shandur Pass

May 072 days later Gupis, Pakistanphoto_camera23videocam 0comment 0

Gupis, Pakistanphoto_camera23videocam 0comment 0 -

33You Want More.....? Are You Sure.....?

May 083 days later Gilgit, Pakistanphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 1

Gilgit, Pakistanphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 1 -

34Heaven on Earth at Eagle's Nest Hotel, Duikar

May 094 days later Duikar, Pakistanphoto_camera19videocam 0comment 1

Duikar, Pakistanphoto_camera19videocam 0comment 1 -

35The Solitude of a Dawn in Duikar

May 105 days later Karimabad, Pakistanphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 3

Karimabad, Pakistanphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 3 -

36Photo Gallery of Karimabad and the Hunza Area

May 105 days later Karimabad, Pakistanphoto_camera22videocam 0comment 2

Karimabad, Pakistanphoto_camera22videocam 0comment 2 -

37Our Man From Waziristan or "Titanic!"

May 116 days later Sost, Pakistanphoto_camera20videocam 0comment 0

Sost, Pakistanphoto_camera20videocam 0comment 0 -

38A Public Bus Over the Khunjerab Pass Into China

May 116 days later Khunjerab Pass, Pakistanphoto_camera21videocam 0comment 0

Khunjerab Pass, Pakistanphoto_camera21videocam 0comment 0 -

39Our Top Tips for Crossing the Khunjerab Pass

May 127 days later Khunjerab Pass, Chinaphoto_camera2videocam 0comment 0

Khunjerab Pass, Chinaphoto_camera2videocam 0comment 0 -

40At Home in Lovely Tashkorgan - We Find Hunza Man

May 138 days later Tashkorgan, Chinaphoto_camera12videocam 0comment 0

Tashkorgan, Chinaphoto_camera12videocam 0comment 0 -

41Two Taxis and a Slow Trip to Kashgar

May 149 days later Kashgar, Chinaphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 0

Kashgar, Chinaphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 0 -

42Evocative Old Kashgar

May 1510 days later Kashgar, Chinaphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0

Kashgar, Chinaphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0 -

43Photo Gallery of Kashgar

May 1510 days later Yarkand, Chinaphoto_camera18videocam 0comment 0

Yarkand, Chinaphoto_camera18videocam 0comment 0 -

44Southern Silk Road - Tracking the Taklamakan

May 1611 days later Keriya (Yutian) , Chinaphoto_camera16videocam 0comment 0

Keriya (Yutian) , Chinaphoto_camera16videocam 0comment 0 -

45Tazhong - Drawing Chickens in the Taklamakan

May 1712 days later Tazhong, Chinaphoto_camera23videocam 0comment 0

Tazhong, Chinaphoto_camera23videocam 0comment 0 -

46Desert Devils of the Taklamakan

May 1813 days later Korla (Bayingol), Chinaphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0

Korla (Bayingol), Chinaphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0

Comments

2025-05-22

Comment code: Ask author if the code is blank

Bomburet, North West Frontier Province, Pakistan

Bomburet, North West Frontier Province, Pakistan

Sylvia Murray

2011-11-22

Wendy, a wonderful story and fabulous pictures. A very entertaining read!