We woke up stiff and cold in our icy hotel room. Even with the additional gollie coating to my blankets, I was still cold. Thankfully we had electricity that morning and after a boiling hot shower and a simple breakfast of toast and jam, we were ready to hit the road.

An early morning start had been organised as we were heading off to China by public bus over the mighty Khunjerab Pass; its meaning being literally "Valley of Blood", a reference to local bandits who once took advantage of the fearsome and isolated terrain to plunder caravans and slaughter merchants. At a maximum altitude of some 5,150 meters, weather conditions could at any time deteriorate and given the rough condition of the Pakistan side of the Karakoram Highway, the journey was always going to be unpredictable. Our trip across the border could have been delayed or even cancelled for some days. And the thought of being stranded in Sost for more than one night was daunting.

We had crossed the pass in reverse on our first visit to Pakistan from China in 2009 and we knew first hand just how changeable the weather conditions could be. Even though it was late Spring, it was bitterly cold in Sost and we knew that during our trip we would more than likely be facing snow storms and at the very least, icy gale like conditions.

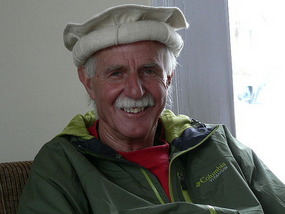

Sadruddin, in his typically brotherly fashion was worried about us travelling without a packed lunch and tried to persuade us to let him organise some prepared food from the PTDC Hotel. We laughed, saying we would be fine. We had biscuits I had bought in Karimabad as well as packets of nuts and nibblies. Sadruddin insisted that at the very least we should take some bars of chocolate, which we accepted gratefully.

Sadruddin's friend Jan met us at the hotel. He was working with the Immigration people in Sost and had offered to assist us. We were in need of Chinese currency but to our disappointment the Sost money changer was out of Yuan. How many times this has happened to us I cannot count. Thankfully we had carried enough Yuan with us for a couple of days.

One positive side to staying in Sost rather than Passu, is that you are there at the border formalities township first thing and don't have to worry about possible, and very likely, delays due to road damage or repair on the way. And conveniently, you can walk to the Immigration and Customs centre from the PTDC Hotel.

We seemed to wait for ever for the officials to arrive at Immigration. And then it was like something out of a B Grade comedy movie. A tall, middle aged officer with an enormous curled moustache eventually arrived. Carrying a stylish walking cane and bearing a much practised distinguished manner, the officer strolled imperiously into the room surrounded by a number of nervous aides. With an air of great importance, he slowly opened an envelope containing the list of passengers and perused it for at least ten minutes, occasionally peering at us over his spectacles. The ceremony was followed by the passport perusal process, taking an even longer period of time. We were asked what country we were from and then ushered down to another room. It was all very polite but quite amusing, and highly reminiscent of the old British Raj. In the meantime our luggage was rummaged through by Immigration inspectors.

The spartan Chief Immigration Inspector's room bore a formality that reminded us more of an Interrogation Room, except the officials were well mannered and friendly. We stood in the grotty cold and forbidding room until Jan arrived and organised some chairs in which we were ordered to sit. And finally, the command was given to a number of hovering staff to boot up the computers. A ceremonial dusting process took place. It was quite a performance. Two officials took out cloths from a drawer and shook them profusely, showering us and the computers in a cloud of dust. The computers were meticulously dusted and the screens lovingly wiped with a moist rag. The computers took about ten minutes to boot up while the officials sat sadly gazing at them. It was all rather amusing, if somewhat tiresome. The staff however were very polite and it certainly was lot more pleasant than our experience with officials in Iran. Just a bit quirky...

We had been expecting to travel by mini bus and were somewhat surprised that our NATCO (Northern Areas Transport Company) bus was a large vehicle with a capacity for around 40 or so people. Sadruddin ensured that we had good front seats and we bade him a sad farewell. We had loved every minute of our stay in Pakistan and were so pleased that we had made the last minute difficult decision in Dubai to continue with our plans to travel there. We had placed all our faith in Ishaq and Sadruddin and they had not let us down. Our entire trip in Pakistan was wonderful and we were sorry to be leaving this country in which we had fallen in love. Our sadness in leaving however was tempered by our promise to return the following year.

Although scheduled to leave at 9.30 am, our bus did not depart Sost until nearly midday. Our thirteen passengers were a diverse but friendly lot. Highly reminiscent of our 2009 trip, a middle aged large Uighur businesswoman with more luggage than seemed possible stacked the entire inside of the bus with her goods. Included also in our newly formed Khunjerab Pass "team" was a lovely Chinese Canadian backpacker Brian Low, a friendly Chinese business man who was the manager of one of the local Pakistani copper mines, a Chinese man who had recently married a Pakistani woman and taken out Pakistani citizenship, several Uighur men and a number of Pakistani men. Two police guards accompanied us on the bus until we reached the last check post before the Khunjerab Pass. All were friendly and delightful company. The poor man who married the Pakistani woman was the only person who was given a very tough time by the officials, there being some dire problem with his recent Pakistani citizenship.

The journey reminded me of one of the "outdoors adventure" management programs I had been involved with in my former working life. The principles were identical. A degree of bonding takes place over a series of experiences, or perhaps in this case more like adventures. All language, cultural and any other differences are overcome and everyone becomes part of the team. A bit scary, I always thought.

For so few passengers the bus was huge but there was very little room to move, thanks to our Uighur friend's luggage. Interestingly, all the luggage was place inside the bus. In hindsight, with such few passengers this was a good move. We had been warned by the Lonely Planet Guide that should the bus breakdown or be held up by road or weather conditions, then it can be almost impossible to access luggage stored on the outside of the bus. On the long and high trek over the Khunjerab Pass, it is deemed essential to have sufficient warm clothing and food. During our trip, I reflected on our decision not to take Sadruddin's offer of pre-packed food but it was a bit late by then.... At least we had warm clothing.

Our bus driver spoke very good English and was very obliging, stopping if we needed toilet stops or even just to take photos. About 35 kilometers along the narrow, bleak and winding Karakoram Highway we reached the security and national park checkpoint of Dih. There was not a lot to Dih, just a funny looking peaked roof cottage with guards and thankfully a toilet. It was not an insignificant spot to stop though as it is where foreigners have pay US$4 cash to enter the 2,270 square kilometers Khunjerab National Park. It is as well to keep this in mind as no other currency is accepted. I'm not sure what happens if you don't have the right money. Dih did not look like a great place to hang out.

Just before the final police check point our two entrepreneurial chameleon police guards became money changers. The Pakistani passengers who were obviously well versed on this procedure, immediately ran to the front of the bus to change money. Typically, by the time we woke up to the situation, the money changers had run out of Chinese Yuan and returned to being police guards. Amazing.

From here to the Pass, landslides and roadworks caused delays and made for a difficult and perilous journey for our poor driver and his bus. Large boulders littered the highway and every so often the bus had to stop and the driver and passengers would leap out and lift the rocks out of the roadway. In one spot about half of the highway had been chomped away, almost as if some huge beast had bitten a hole in it. At one stage, Brian Low anxiously pointed toward a glittering movement down the vertical mountainside only meters from the side of our bus. It was the reflected light from masses of small pebbles accelerating rapidly down the mountain slope onto the road. We nodded, acknowledging that we had seen it. No-one said a word though.

It was not a trip for a faint hearted driver and the entire journey certainly became a team effort.

And suddenly, our bus was bogged up to the back axels in deep, deep gravel that was been laid down by the Chinese road workers. We were not concerned as there were heaps of road workers with their super heavy road equipment. The only problem was that the bus did not have winch cables, nor even ropes or a proper shovel. And the road workers could - or would - not come to our aid. By then snow began to fall heavily and there was no option other than for the passengers to disembark and try to shovel and push the bus out of the gravel bog. When I say the bus was large - it was the size of an ordinary Australian commuter bus - bloody huge.

Two athletic Pakistani fellows took turns in using a broken handled shovel to dig as best they could the back axels out of the gravel. It was to no avail. As soon as the axels were clear the driver just hoofed the old bus, wildly spinning the wheels and driving it deeper into the gravel. Our Chinese copper mine manager was non-plussed about lack of tools and the driver's ineptitude, sadly prophesying doom and gloom. We would be there all night, he predicted with great certainty. Watching the process, we thought this was entirely possible.

All the passengers became diggers and pushers. After an hour of shovelling, the axels were at last totally clear and as we pushed with all our might the old bus groaned and finally lurched free of the gravel, spinning wheels and covering us all in a cloud of fine white powder dust and choking black diesel smoke. To our horror, the driver began to slow down to stop for the passengers. We all screamed and yelled for him to keep going, to avoid another bogging scenario and thankfully he managed to drive the bus onto secure ground. We were very grateful to be back on the bus but all decided that the driver needed some tuition in what not to do in a bogging situation...

The road wound in steep snaking curves up to a wide, flat area we recognised as being the entry to the infamous Khunjerab Pass. It was snowing heavily and the river running along side of the road was totally frozen over. In the filmy snowscape, a large and imposing cement arch of distinctly Chinese character was just visible. This was the border into China. Our driver obliging stopped for us to take photographs and a smoke stop for the smokers. It was rather a surreal experience. The scenery was breathtakingly beautiful. Isolated and haunted. Conical snow coated mountains stood alone like massive ice cream cones and in the distance ancient snow covered volcanic peaks soared into a wild and violent sky.

Another four kilometers on we arrived at the bleak site of the Chinese Customs Check Post, a stark and forbidding concrete block plonked literally in the middle of no-where. Poor thin guard dogs surrounded our bus and then the bureaucracy began. "Everybody off. All luggage off" barked a stern faced official. This was a nightmare for our heavily laden Uighur business woman, although she must have been used to the procedure. In hindsight, it was probably more of a nightmare for the obliging passengers who so generously helped her.

The poor Uighur and Pakistani passengers were given a very tough time by the officials. Every one of their bags was opened and the contents reefed out and thrown on the concrete floor. Even their jackets were taken off and the poor young Uighur and Pakistani guys stood out in the bitter cold, looking powerless and miserable. We watched with concern as Mrs Uighur's bags ruptured, spilling out its vital booty of onions, potatoes and carrots. The officials looked on coldly, making no effort to help her.

All items, even jewellery, watches, cameras and passports had to be conveyed through an x-ray machine. Needless to say the whole process took hours and we were relieved that we only had thirteen passengers. The building even inside was freezing cold and we watched shivering at the coming inspection process.

We were dreading our turn for the luggage inspection. The officials however were relatively friendly and polite toward us. But to our concern they seemed more than interested in our passports. Our stomachs froze as we wondered what the problem was. To our surprise our Chinese official began to laugh and pointed excitedly at our visa stamps. It seemed he was fascinated that we had travelled to Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Iran - and all the other staff were too, peering and laughing at our passports. We laughed too, highly relieved to survive the inspection process. It was a bit like Customs when we arrived in Iran. We felt almost guilty with absolutely no reason. Together with Mr Copper Mine and a relieved Brian Low, we were courteously escorted to another freezing cold room where we waited for some considerable time for our less fortunate passenger friends to be processed.

Mr Copper Mine who regularly crossed the border to and from Pakistan explained that the Chinese officials were particularly tough at this crossing because some 60% of all drug seizures into China had been found there. Perhaps they were also concerned about the Uighur unrest in Xinjiang Province and possible relationships with Pakistani militant groups. Who knows....

Meanwhile Alan and Mr Copper Mine decided it was a fine time to find a toilet. Thanks to our Chinese friend, the officials reluctantly allowed them to use, under the close escort of two armed guards, what they described as a filthy squat arrangement. They were amused that they were not allowed to use a newly built modern porcelain toilet right next to the squats. I was glad I didn't have to bother.

Four heavily armed army personnel escorted our bus to Tashkorgan. All sat down the front with us and smoked like chimneys.

We had not expected the journey to take so long. Although we realised that we would gain an additional three hours in time by crossing the border (all of China is on Beijing time), we were surprised that by the time we left Customs, it was nearly sunset and 7.30 pm China time. And we knew that we had to pass through tedious Immigration procedures when we arrived at Tashkorgan, our first destination in China.

Brian Low, who was a logical young man asked two questions of the passengers:

1. Why does the NATCO bus leave so late when the border process takes so long and we lose three hours on our entry into China?; and

2. Why are Customs and Immigration on the China side so far apart? The No Mans Land zone from the Khunjerab Pass to Immigration Tashkorgan is 143 kilometers which means you cannot disembark for a toilet stop for such a long time.

Needless to say, no-one had the answers.

And it was a long, long 143 kilometers to Tashkorgan. Even though we were descending quite rapidly from the Khunjerab, our bus was travelling at a slower and slower speed. Brian looked over at the driver's shoulder at the speedometer and asked us why we were only travelling at 60 kilometers per hour on what was by then a perfectly good highway.

Again no-one had an answer*

Brian and several of the passengers were planning to travel on another 250 kilometers to Kashgar and were anxious to arrive as early as possible at Tashkorgan to secure a joint taxi trip. We were also anxious to get to Tashkorgan as early as possible as we realised that it was becoming very uncertain that we would be able to buy food when we arrived. If only we had taken Sadruddin's advice. A packed meal of cold potatoes, eggs and Tandoori chicken like we enjoyed at Shandur Pass would have been very welcome!

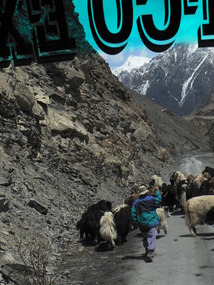

Tundra landscape gave way to desolate rolling hills with occasional farms housing yaks, djus, cattle, sheep and goats. It was still bitterly cold and the isolated windswept environment was bleak and forbidding. Heavily clad Tajik women tended the animals and several people we saw were cleaning the chimneys of poverty stricken houses. It was a desperately harsh environment in which to live.

Some 50 kilometers out of Tashkorgan we encountered a violent dust storm and visibility was reduced to less than 500 meters. We had stayed in Tashkorgan twice before on our travels and were well aware of the sudden and frequent occurrence of dust storms arising from the massive Taklamakan Desert. Our bus slowed to a near standstill.

To our delight Immigration procedures were virtually a breeze. There were no goodbyes. Our passenger friends departed as rapidly as we did and we were disappointed not to have exchanged email addresses. Perhaps Brian Low or someone who knows him may contact us one day through Travelpod!

We walked to our Crown Inn Hotel from Immigration. It was by then 10.30 pm China time and dark. We just hoped that we would remember the way from our last visit. Few people in Tashkorgan spoke English and it was certain no-one would be able to help us if we got lost. Thankfully, Alan unlike me, has a good sense of direction...

Not surprisingly, the Crown Inn chef had just left for the evening and we could not buy any food from the hotel. At the suggestion of the manager, we hoofed it across the road to a general store which was just closing. To our delight we were able to communicate somehow with the friendly staff and purchase some nuts and what turned out to be potato chips, as well as a bottle of dubious looking red wine and some beer. Dog tired and sitting on our bed, we giggled at our unhealthy meal. What would our good health promoting friend and Gutbuster founder Garry Egger think, we laughed. The beer was fine but the wine was simply shocking. If we couldn't drink it, it had to be really bad. But we knew that the Crown Inn had great breakfasts and we were just pleased to be back in our beloved township of Tashkorgan.

* Later in our travels through Xinjiang we learnt that the Chinese government had recently imposed extremely strict speed limits on Xinjiang roads; even highway speeds could be reduced for no apparent reason down to as low as 20 kilometers an hour. And there was no way drivers could take risks. Speed cameras were everywhere and often ones that averaged speed times. On other occasions, drivers were given designated times to reach their destinations. It was a particularly frustrating situation.

More Photos of Crossing the Khunjerab Pass

[

A Public Bus Over the Khunjerab Pass Into China

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

Khunjerab Pass, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan

Khunjerab Pass, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan

Other Entries

-

21A Gorgeous Carpet, Jolfa and Fascinating Abyaneh

Apr 3011 days prior Abyaneh, Iranphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 0

Abyaneh, Iranphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 0 -

22Photo Gallery of Abyaneh Village

Apr 3011 days prior Abyaneh, Iranphoto_camera13videocam 0comment 0

Abyaneh, Iranphoto_camera13videocam 0comment 0 -

23Destination Tehran - Reflections on our Travels

May 0110 days prior Tehran, Iranphoto_camera13videocam 0comment 0

Tehran, Iranphoto_camera13videocam 0comment 0 -

24Osama bin Laden Dead - Our Travel Plans in Chaos

May 029 days prior Dubai, United Arab Emirates, United Arab Emiratesphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0

Dubai, United Arab Emirates, United Arab Emiratesphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0 -

25For Better or For Worse - We Head off to Islamabad

May 038 days prior Islamabad, Pakistanphoto_camera4videocam 0comment 0

Islamabad, Pakistanphoto_camera4videocam 0comment 0 -

26Eclectic Chitral - North West Frontier Province

May 047 days prior Chitral, Pakistanphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 0

Chitral, Pakistanphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 0 -

27The Wonderful Faces of Chitral Town

May 047 days prior Chitral, Pakistanphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0

Chitral, Pakistanphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0 -

28A Four-Seater Jeep, Six People & Two Kalashnikovs

May 056 days prior Bomburet, Pakistanphoto_camera15videocam 0comment 1

Bomburet, Pakistanphoto_camera15videocam 0comment 1 -

29Love Affair with Rumbur, A Sick Jeep Trip to Buni

May 065 days prior Buni, Pakistanphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 0

Buni, Pakistanphoto_camera9videocam 0comment 0 -

30Insight into the Life of the Lost Kalasha People

May 065 days prior Buni, Pakistanphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 3

Buni, Pakistanphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 3 -

31More Photos of the Kalasha Peoples

May 065 days prior Buni, Pakistanphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 0

Buni, Pakistanphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 0 -

32Tandoori Chicken, Potatoes & Eggs at Shandur Pass

May 074 days prior Gupis, Pakistanphoto_camera23videocam 0comment 0

Gupis, Pakistanphoto_camera23videocam 0comment 0 -

33You Want More.....? Are You Sure.....?

May 083 days prior Gilgit, Pakistanphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 1

Gilgit, Pakistanphoto_camera14videocam 0comment 1 -

34Heaven on Earth at Eagle's Nest Hotel, Duikar

May 092 days prior Duikar, Pakistanphoto_camera19videocam 0comment 1

Duikar, Pakistanphoto_camera19videocam 0comment 1 -

35The Solitude of a Dawn in Duikar

May 101 day prior Karimabad, Pakistanphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 3

Karimabad, Pakistanphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 3 -

36Photo Gallery of Karimabad and the Hunza Area

May 101 day prior Karimabad, Pakistanphoto_camera22videocam 0comment 2

Karimabad, Pakistanphoto_camera22videocam 0comment 2 -

37Our Man From Waziristan or "Titanic!"

May 11earlier that day Sost, Pakistanphoto_camera20videocam 0comment 0

Sost, Pakistanphoto_camera20videocam 0comment 0 -

38A Public Bus Over the Khunjerab Pass Into China

May 11 Khunjerab Pass, Pakistanphoto_camera21videocam 0comment 0

Khunjerab Pass, Pakistanphoto_camera21videocam 0comment 0 -

39Our Top Tips for Crossing the Khunjerab Pass

May 121 day later Khunjerab Pass, Chinaphoto_camera2videocam 0comment 0

Khunjerab Pass, Chinaphoto_camera2videocam 0comment 0 -

40At Home in Lovely Tashkorgan - We Find Hunza Man

May 132 days later Tashkorgan, Chinaphoto_camera12videocam 0comment 0

Tashkorgan, Chinaphoto_camera12videocam 0comment 0 -

41Two Taxis and a Slow Trip to Kashgar

May 143 days later Kashgar, Chinaphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 0

Kashgar, Chinaphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 0 -

42Evocative Old Kashgar

May 154 days later Kashgar, Chinaphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0

Kashgar, Chinaphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 0 -

43Photo Gallery of Kashgar

May 154 days later Yarkand, Chinaphoto_camera18videocam 0comment 0

Yarkand, Chinaphoto_camera18videocam 0comment 0 -

44Southern Silk Road - Tracking the Taklamakan

May 165 days later Keriya (Yutian) , Chinaphoto_camera16videocam 0comment 0

Keriya (Yutian) , Chinaphoto_camera16videocam 0comment 0 -

45Tazhong - Drawing Chickens in the Taklamakan

May 176 days later Tazhong, Chinaphoto_camera23videocam 0comment 0

Tazhong, Chinaphoto_camera23videocam 0comment 0 -

46Desert Devils of the Taklamakan

May 187 days later Korla (Bayingol), Chinaphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0

Korla (Bayingol), Chinaphoto_camera11videocam 0comment 0 -

47Toward Urumqi - Siamese Mountains and Wind Farms

May 198 days later Urumqi, Chinaphoto_camera3videocam 0comment 0

Urumqi, Chinaphoto_camera3videocam 0comment 0 -

48A Day in Urumqi and The Fabulous Erdaoqiao Markets

May 209 days later Urumqi, Chinaphoto_camera6videocam 0comment 0

Urumqi, Chinaphoto_camera6videocam 0comment 0 -

49R & R in the Extraordinary City of Shanghai

May 2110 days later Shanghai, Chinaphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 0

Shanghai, Chinaphoto_camera10videocam 0comment 0 -

50A Remarkably Unremarkable Journey Home

May 2312 days later Crowdy Head, Australiaphoto_camera1videocam 0comment 1

Crowdy Head, Australiaphoto_camera1videocam 0comment 1

Khunjerab Pass, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan

Khunjerab Pass, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan

2025-05-22