AN UNEASY START OR "HOLY SHIT!"....

The day dawned pale and white; a feeble sun just a faint pearly glow in a featureless milky sky. Snow had fallen the evening before encapsulating buildings, cars and covering the ground in a luxuriant thick white blanket. Bilibino town was painted silver-white, the horizon barely distinguishable from the land and the sky. Fur hatted people in snow speckled overcoats trudged through the deep drift tracks, heads down as they forged through the bitter cold. It was, apparently minus 37 degrees C.

Unlike the last brilliantly sunny days, the world outside looked sombre and forbidding. Perhaps the glorious benign weather we had experienced on our first days in Bilibino had lulled us into a false sense of security about the perils of Arctic life?

It wasn't a great start to the day. Not only did the weather look formidable, we both woke up with concerning stomach cramps and well.... thank god for the Lomotil, the ultimate "Travellers' Friend". Just what we needed was a bout of diarrhoea for our long 6WD Trekol trip on the ice road to Pevek....

We faced our day with a mixture of genuine excitement tinged with just a few pangs of apprehension. We had been really looking forward to the ice road journey; a unique opportunity to see first hand the real Arctic, its geography, vegetation and perhaps even some animals. But we had been well warned about its perilous nature and although we expected it may be the highlight of our travels, we knew it could end up an event we could well regret.

Alex joined us for breakfast and briefed us again about what we should wear and how we should prepare for our coming journey. Unusually serious, he again reminded us "The cold is no joke. Make sure you have your very warm clothing close at hand in case 'anything goes wrong' and you need to change into something warmer. And you will need to eat well too..." Alex, like most of our Russian friends thought we ate like birds.

We had in fact, found we were very often over dressed. All the buildings which we had been in were very well heated, if overly so, and often we found ourselves rapidly peeling clothes off because we became so uncomfortably hot. We decided to wear our best thermals under micro fleece jumpers and trekking trousers and keep our bib and brace overalls, as well as our anoraks nearby. God knows however, how we would be able to put them on in the Trekol if "anything did happen...".

Just before we left our hotel we received two sms messages, both co-incidentally headed "Holy Shit!" One was from our close friend Sue and the other from our friend Cameron, the ABC* morning radio announcer for our home region; both avid followers of our rather bizarre travels. They had realised that morning we were about to head off on our ice road adventure - and they had also just heard about Alan's snow mobile accident and my dog sledding incident. Their concern and numerous "take care" messages were kind and thoughtful.

Surely we thought, with all their well wishes and our travel agent Elena's "prayers for our safe passage", nothing too malevolent could happen to us, could it?

*Australian Broadcasting Commission

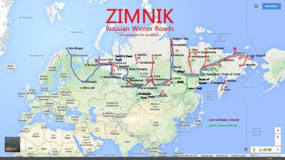

ICE ROADS OF RUSSIA

"Most of the Russian far north is completely roadless. Whole villages, towns, and cities lie beyond any road or rail network. In summer they are supplied by boats which ply every one of Siberia’s great north-flowing rivers. In winter, however, a vast network of ziminki (ice roads) open up....". (Arctic Russian Travel).

Ice roads are winter routes, their base being naturally frozen water. They can be formed on a river, lake, over muskeg or an expanse of frozen sea. Ice roads offer temporary transport to isolated areas with no permanent road access. Generally, they are built in areas where the construction of roads is expensive due to boggy muskeg land, a common phenomena in Arctic regions where permafrost prohibits the drainage of melted snow and ice. An ice road can be formed for use of a car or small truck when the ice is more than 22 cm thick. The minimum thickness seemed awfully thin to us. Even when we were travelling across the Arctic Ocean at Pevek on 80 cm thick ice, we felt highly vulnerable!

The roads are particularly useful as they generally provide a flat, smooth driving surface devoid of trees, rocks and other obstacles. They are mostly used for the transport of provisions by truck to smaller isolated settlements.

These roads however, present significant danger to those driving over them. Speeds are typically limited to 25 kilometers per hour to prevent a truck's weight from causing waves under the ice surface which can damage the road or dislodge ice. Pressure ridges or breaks in the ice due the the expansion and contraction of the ice surface are also another real hazard.

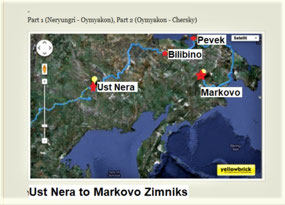

The Bilibino to Pevek zimnik is part of the 4,000 kilometer Arktika - Markovo Zimnik which stretches from Ust Nera via Bilibino and Pevek to Mys Shmidta, Anadyr and down to Markovo. According to gentlemanadventurer.travellerspoint "Less than a dozen foreign expeditions have mastered those roads. The locals use them regularly of course, especially for truck transports."

After our journey, we heard that we were the first foreign tourists to have completed the Bilibino to Pevek leg. Whether this is correct or not, it makes for a good blog entry!

OUR JOURNEY BEGINS

Meeting Anatoly and Our Ancient Trekol

During the organisation of our travels, Elena had sent us photos of the type of 6WD vehicles or Trekols, we would be travelling in on our ice road journey. Perhaps it was to make us feel a bit better about paying the whopping USD 3,800 for the vehicle hire? But of course, there was no point in worrying about the cost. There was no option and without travelling to Pevek, we would not have undertaken our tour of Chukotka. Whatever the case, we could not help but be very impressed with the photos she had sent to us super looking mega vehicles, all shiny and of course brand new....

To Alex's concern however, not only were we provided with only one and not two Trekols, but our vehicle was really, really ancient. Hmm, not quite like the photos...

The truck yard from which we had hired our Trekol had not improved. The poor guard dog was still chained up. Other hungry looking dogs roamed the yards. And the management was looking decidedly unfriendly. The place was covered with old truck parts and a staggering mass of frozen orange dog piss stalagmites. It was quite a revelation to us. We had no idea that urine changes to such an iridescent colour once it freezes. We were soon to learn that in such extreme temperatures, it is very obvious where you relieve yourself!

Anatoly was our driver. An older and not especially fit looking man (probably a lot younger than us), he was to Alex's relief a very experienced driver and as we were to find out, an excellent mechanic....

Initially, Anatoly greeted us with the usual suspicion and gruffness to which we were becoming accustomed, but during our journey became very friendly and very caring, offering us his food and tea and thankfully making sure we had enough toilet breaks.

Trekols are necessarily built like tanks, very high off the ground and about as comfortable. Anatoly must have thought I looked particularly decrepit as he literally shoved me by the rear end into the front cabin seat, making it absolutely certain that it was where I was going to sit. Alan and Alex were to share the rear compartment, perched on narrow bench like seats with no windows. I half heartedly offered to swap with Alan who was still suffering from his poor broken ribs but he nobly refused. And well after all, someone had to take the photos....

Of course, no-one had any seat belts. The Trekol was probably built before they were invented. Unlike Alex however, we were enormously excited and certainly not thinking about possible dangers; just the thrill of the upcoming adventure. Bugger the seat belts.

A white pigeon landed on, then flew off the bonnet of our Trekol just as we departed. That had to be good karma...

On the First Part of the Journey....

"Overland travel is limited to an ice road from Bilibino that can be traversed by 4x4 vehicles. Travelling in convoys is strongly recommended". Wikivoyage.

We said goodbye to Bilibino, driving through depressing outskirts of snow engulfed building corpses and the stark remains of old abandoned mining sites. Some ten minutes out of town we met up with our convoy of three 8WD trucks: an oil tanker and two oversized freight trucks which were picking up supplies of oil and goods stored at the now frozen Port of Pevek for return freight to Bilibino. Our Trekol led the way, plodding along at a steady 40 kilometers per hour. Here is our first few kilometers out of town https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rWok7O-hhzI.

The first part of our journey was along a relatively wide stretch of snow road flanked on each side by larch and small ground hugging coniferous cedars. I was spell bound by the sheer remoteness of the environment; the magnitude of nothingness that would be our travelling companion for nearly another whole day.

Colour had seemingly forgotten the tundra, yet the monochromatic landscape was fascinating. The sky and the surrounding countryside were essentially white, relieved only by occasional patches of glassy blue-black ice.

Naked black tree trunks, vertical bare stems of deciduous shrubs and an occasional soaring eagle were the only signs of life in an arctic lunar landscape. But the stark scenery was simply beautiful. And I was loving every minute of it.

Here is some of the countryside https://youtu.be/fAfJ3opqK1k.

I thought of the lyrics to A Horse With No Name. Yes, on the first part of the journey we were still travelling through Arctic taiga (forest), there were plants and rocks and birds and things and the sky certainly had no clouds... Soon we were to meet the tundra, virtually a frozen ocean-desert in the Arctic - and with a life underground and a perfect disguise above.....

"On the first part of the journey

I was looking at all the life

There were plants and birds and rocks and things

There was sand and hills, and rings...

And the sky with no clouds..."

I was looking at all the life

There were plants and birds and rocks and things

There was sand and hills, and rings...

And the sky with no clouds..."

"The ocean is a desert with it's life underground.

And a perfect disguise above.

Under the cities lies a heart made of ground.

But the humans will give no love" ("A Horse With No Name", America)

And a perfect disguise above.

Under the cities lies a heart made of ground.

But the humans will give no love" ("A Horse With No Name", America)

Where the Tundra Begins & Our First Break Down

Some forty minutes into our journey, the countryside became mountainous and the vegetation became noticeably more sparse. Some thickets of larch were apparent on sides of the steep slopes, probably we thought as it was being given some sort of protection by the mountains. In Anatoly's opinion however, vegetative growth here was a factor of the terrain and not of the climate. Alex told us that it was now minus 39 degrees C outside. It was hard to imagine how any plants could withstand this extreme climate, let alone the dry rocky dry terrain.

The road although it looked flat, was surprisingly rough with Anatoly having to hang onto the steering wheel to keep the vehicle within the boundaries of the track. But we had seen nothing yet... I wondered guiltily how Alan was faring in the back compartment on those hard plank seats with his broken ribs. But to my relief he was sounding happy, engaged in an animated conversation with Alex.

Ahead, the sky was beginning to darken; the sun a dim sphere barely distinguishable in the steely sky. Anatoly thought there could be a blizzard ahead. "How long can we stay in the car if we get stuck in a blizzard?" we asked. Anatoly replied that we had enough fuel (to keep us alive without freezing) for four days. But that was of course if the engine was still able to keep going.... At this stage my phone recorder voice changed from euphoric to slightly doubtful. I had not thought of what would happen if the engine failed. But of course there was the convoy of other trucks....

Almost as if on cue, our Trekol started to slow down. Anatoly's face was not reassuring. We pressed on for a kilometer or so until finally we stopped. Apparently at temperatures lower than minus 30 C, diesel begins to thicken and can easily clog up the carburetor.

A console between the driver's seat and me contained every type of mechanical instrument you could imagine but of course, poor Anatoly could not find the fuel filter he needed. Finally, he left the vehicle, braving the now quite intense wind and using a type of step ladder to crawl with much difficulty into the bonnet of the Trekol. He then had to light a blow torch to heat up the offending part before replacing the filter and returning it back into the engine. The job was unbelievably difficult. The blow torch refused to light and the filter refused to fit. Anatoly was not an agile man and the effort was obviously exhausting him. And there was nothing we could do to help.... It was to be the first of many fuel blockages we were to encounter on our ice road journey.

Depths of the Tundra OR a House That Fell off the Back of a Truck

We were now travelling through real tundra. There was virtually no plant growth and the definition between the land and sky had all but disappeared, only a faint nib outline of the distant white mountains was visable. The environment could well have been a fine pen and ink drawing.

The road had deteriorated to tyre tracks in the snow, and just veering slightly off the track could - and obviously did - result in a serious bogging. Several massive bog holes of at least a meter in depth and long lost trucks wheels, were testament to the fate of some unfortunate trucks. In other places, sheets of glassy blue ice made our going even more treacherous.

We were surprised (and somewhat reassured) how many trucks were using the road. And they were all massive 8WD vehicles. Apparently, the road had been unusable due to severe weather just a few days before our arrival in Bilibino and truck drivers were understandably anxious to pick up goods from Pevek. But passing the trucks was not an easy feat. It was customary for lighter vehicles to make another track to pass the heavier trucks. To do so however, was hazardous. Anatoly would take a path around the truck, then if our Trekol was beginning to sink, would reverse then back and fill until he had "made" another hard packed route around the truck. It didn't always work and several occasions, he was forced to try a number of different tracks. Here is a video of our Trekol parked off the route while waiting for four trucks to pass (commentary Alex) https://youtu.be/iCf1KS1rwyc.

Like some sort of bizarre apparition, a small wooden hut appeared from nowhere. Sunk on its side at a precarious angle, it was almost fully buried in deep snow. Anatoly told us it had "fallen off the back of a truck" some months ago. It was he said, unlikely that it would be able to be removed until the summer snow melts; and perhaps never given the unstable nature of the muskeg ground during the warmer season. This sure was a very different world....

We asked Anatoly about the use of snow mobiles along the ice road. Yes, he replied. There had been some "crazy people" who had ridden snow mobiles from Yakutsk to Kamchatka. We thought about one tour we had looked at in the tourist literature which involved a six hundred kilometer ride by snow mobile. It was described as "fine for first time snow mobile riders". OMG! After our ten kilometer experience with snow mobiles in Magadan, we could not imagine how this trek could be undertaken, especially by novice riders. The Trekol was feeling good...

Perilous Conditions in the Tundra: Our Trekol Falls Into a Deep Hole

Weather conditions were deteriorating and visibility had decreased to around 200 meters. Ahead were several trucks but it was difficult to decipher their distance from us. Here is a video clip of us passing a truck in difficult conditions. https://youtu.be/NFqTsZu8acI

Anatoly was obviously having trouble with seeing where the road led, his only points of reference were the lines of upright poles driven into the side of the road and occasional metal 44 gallon drums placed as markers. He apparently told Alex that if conditions worsened, he would have to stop until nightfall when the glare was minimised and it was easier to see.

After passing several trucks we came around a bend in the road to find the curious sight of a road works grader and a log cabin. Apparently the grader dragged the hut along with it as it conducted road works and the hut was used to accommodate the workers. When Alex explained the situation, it made a lot of sense but it really did look quite bizarre. How the road workers worked in these conditions and lived in this tiny hut, didn't bear thinking about.

As the blizzard began in earnest, Anatoly struggled to keep our old Trekol on the route. The road surface was shocking; deeply rutted and and in places so boggy our sturdy vehicle could barely maintain traction. Conditions were becoming atrocious, wild snow flurries making the already limited visibility almost impossible. It became increasingly hard to orientate yourself in the almost white-out conditions. You could really do your head in out here, I thought to myself.... Here is a video of the frightful conditions as we came past the grader https://youtu.be/eLi84JM3UGc

Bang, crash! Our vehicle slammed down a hole so deep that the impact swept me completely off my seat. Alan apparently hit the roof of the vehicle with his back and Alex was found lying on the floor of the cabin, covered with smashed glassware and crockery that didn't survive the incident. Our spare wheel had flown off the front of the Trekol and was lying some fifty meters away. By some miracle, none of us was hurt but it didn't do Alan's broken ribs much good.

And this is just why you must travel in a convoy on an ice road like this. In a short time, one of our convoy trucks (driven by Anatoly's brother) stopped to assist us. After he and Anatoly inspected our Trekol for damage, they threw the spare wheel into the truck and off we set with me housing the wheel fastener between my legs. I couldn't help wonder what would happen if we needed the wheel and tyre and couldn't contact Anatoly's brother....

And talking of communications, it seemed that Anatoly used some sort of CB radio to communicate with the convoy which he did consistently. Meanwhile, Alex was becoming alarmed that our new satellite phone was refusing to work, especially as our Trekol carburetor had blocked again, and would do so another four or five times before we reached our next destination. And poor Anatoly was looking stressed too; the frequent breakdowns obviously having an exhausting impact on him both physically and psychologically.

During one breakdown, Anatoly asked me to swap seats as he needed to access the storage under the passenger seat for more tools. Sitting in the driver's seat, I wondered how scary it would be if anything happened to Anatoly and I may have to take over driving this tank of thing through these conditions. Thankfully it wasn't necessary - and I wasn't asked to take over!

More Breakdowns and Hello Vasily Ivanovich Chapaev!

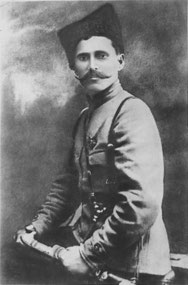

Our poor old Trekol grunted and groaned as our road ascended to higher country. The road was barely visible through the most remote and extremely exposed polar landscape you could possibly imagine. We were in true tundra now; not a tree or plant to be seen. Alex pointed out a beautiful mountain ahead known as Chapaevskoye - or "Place of Chapaev". Vasily Ivanovich Chapayev was a celebrated Russian soldier and Red Army commander during the Russian Civil War. A very colourful and prominent member of the Communist party during Soviet times, he always wore a hat which bore two points. It was thought that this mountain with its two symmetrical peaks, resembled the points of Chapaev's hat; hence the name.

Just past Chapaevskoye, Anatoly stopped our Trekol for yet another fuel filter change. It would be he said, a good opportunity for a toilet stop and to have some tea and lunch. Stiff after our long bumpy journey, we could hardly stumble down from the huge Trekol. Relieving ourselves was not at all easy either; our urine freezing before it hit the ground in a mass of bright orange crystals. And in the howling wind, just doing up trousers was a major effort.

Anyone for Cold Pasta and Reindeer Liver? OR "Safari in Chukotka!"

Anatoly was well prepared. He used a portable gas cooker in the middle of the console to boil an ancient looking kettle, then made us all some tea. Terrified that it may bring on more toilet stops, Alan and I declined - as we did the large plastic containers of cold pasta and reindeer liver he kindly offered to us. It was just a bit too hard to explain our stomach situations.

Without wanting to offend, Alex's instant ramen noodles sounded like a better bet - much to Anatoly's disgust. And unfortunately, we obviously did offend.... The noodles were pretty average too but they certainly hit the spot.

Our journey from here on was rough and perilous. The sky was now a formidable inky blue-black, and the dim light must have made driving very difficult for Anatoly who was now snow ploughing our own pathway as the road had become too rutted to pass safely.

Every now and then our poor Trekol would flounder and nearly bog in the soft snow. And when it did, my passenger door would unlock and open, letting in a jet of icy cold air. While Alex and Alan complained of the heat in the back compartment, I was freezing cold. Anatoly insisted that I don my anorak, mittens and hat while Alan and Alex two reluctantly found me some hand and foot warmers in the luggage. After lugging these heavy sachets half way around the world, I was delighted that they actually worked very well.

Alex asked us if we would like some fruit. He had a bag of apples that he wanted to share but he insisted he needed to wash his apple before eating it. He asked Anatoly to stop the car, and to our astonishment leaped outside in the howling blizzard to wash his fruit with some of our bottled water. Sure this Chukchi fetish for cleanliness was just a bit over the top. We ate ours, dirt and all...

A truck driver radioed in with what sounded like a serious conversation. Alex told us it was one of our convoy who was some distance behind. He had had to stop his truck due to blinding blizzard conditions and the wind was so strong it was actually pushing his stationary vehicle backward.

I thought we were all standing up pretty well but my phone records my now somewhat shaky voice "The wind is absolutely howling and we cannot see at all through the snow flurries. Everything is just white. This must be the most frigg'n remote place on earth..."

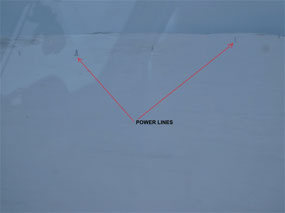

We then sighted some distant power lines. Was it an apparition or were we coming to some sort of civilisation? A number of trucks appeared, several of the drivers stopping to talk with Anatoly about the inclement conditions. The conversation looked serious. But one truck driver was obviously intrigued by Anatoly's strange passengers, asking him what on earth were we doing travelling on the ice road? Alex must have told him that I write travelogues and was it OK if I took a photo of him. "Will I be famous?" the driver apparently asked. Anatoly said that his photo would appear in a well known journal. "What is the magazine called?" he asked. "Safari in Chukotka!" replied our cheeky driver.

Introducing the 19th Corner....

In the howling wind and now snowing conditions, our poor Trekol limped into a curious tiny settlement with a large electricity station right in the middle of well, absolutely frigg'n nowhere.... My first impressions of this god foresaken place are etched deeply in my mind; just one lonely house, some outer buildings, one of which was obviously a toilet, some old truck parts and a huge black dog.

We had reached what is known as The 19th Corner, a hub station for power distribution between Bilibino, Pevek and two other small villages. The keeper of the station with his young family lived full time in the only dwelling on the site; his sole job to adjust the distribution of power between the four settlements. What did his family do all day? Where were his children educated? For how long was he stationed there?

After yet another fuel filter change, Anatoly announced he would have tea inside the house and would rest there until dark when driving conditions were better for vision. We were welcome to join him. A number of other trucks had arrived and the drivers obviously had the same idea. Perhaps the owners of this private establishment welcomed visitors? We didn't think however they would appreciate foreigners so the three of us stayed in the Trekol with the engine running and the heating going full blast, eating a meal of more ramen noodles and instant mashed potato (which was surprisingly good). Outside the temperature had plummeted to minus 42 C.

Then Alex broke the news. Anatoly did not think the old Trekol would make the distance to Pevek. After all, the 19th Corner was only one third of the distance and we had another 230 kilometers to go. We had three options: to have the Trekol towed which would apparently take us another 24 hours, to split us up, each travelling in one of the trucks or the oil tanker; or to just keep going. The last two options were bearable if the Trekol could make it that is. But the thought of another 24 hours being towed slowly along the ice road sounded too awful to contemplate. "Don't worry. It will all work out fine" chirped Alex unconvincingly.

By then I was totally entranced by the solitude of The 19th Corner. This remote settlement was the most alien, forbidding and bizarre place I had ever seen. Just the very name evoked such mystery and intrigue. The opportunity for a photograph shot - and a relief spot - was far too good.

It was not quite that easy. Alex and Alan nobly (or cunningly) allowed me to venture out first. Stunned by the gale force wind, snow and extreme cold, I could barely breathe let alone stand upright in the thigh deep soft snow. And that didn't last long either. In a moment I was lying flat on my back, bowled over the huge but thankfully friendly black guard dog. Eventually however I managed to stumble out, taking as many photos as I could. Out of the corner of my eye, I noticed the vague outline of a woman at the house window; a sad lonely face staring right at me. Looking back at the lonely figure and the strange haunted looking house, I could well have been acting out a strange black and white movie - an arctic Portrait of Dorian Gray?

We stayed at the 19th Corner for another two hours before Anatoly finally decided it was time to go. He would try to make the journey with our Trekol but warned we may have to vacate at any time with all our luggage into the trucks. And what would happen to Anatoly we asked Alex?

On dark, we set off in convoy with our Trekol leading the way. We did not travel more than half a kilometer before the poor old thing broke down again. Anatoly's brother parked his truck to protect us from the frightful blizzarding winds as Anatoly struggled to use the last of the fuel filters. A different type, he said.

We set off into the night, dodging huge craters and heavily rutted areas. After one particularly huge crashing blow, Anatoly apparently asked Alex. "And just what are your friends doing travelling through here in winter?" We collapsed laughing. There was of course no answer at all. At that time, there seemed to be no rational reason either. Anatoly looked confused.

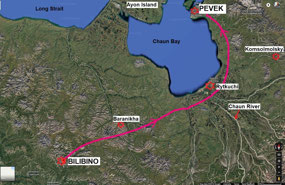

Our trip to Pevek was long and rough. I slept some of the way and just as I awoke Anatoly was telling Alex we had arrived at an ice sealed proper road, the location not far from a mining town called Rytkuchi and the last 100 kilometer leg of our journey before we reached Pevek Town.

It was bliss to be on a sealed surface and where we could travel at speeds around 90 kilometers per hour. And there were lights and life; the road full of trucks spraying the surface with water.

Our Trekol by some miracle made the distance to Pevek without another breakdown. The magic fuel filter must have done the job. But it took a staggering 16 hours to complete our journey.

It was 4.30 am and there was no time for polite farewells. Anatoly heaved our luggage out at the back of what we guessed was our hotel. He was going to sleep in the Trekol before heading off the following day back to Bilibino.

A lovely kind man, we hoped he received most of the money we had paid. He certainly deserved to.

But somehow we knew he wouldn't....

Pevek, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russian Federation

Pevek, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russian Federation

geoff

2018-07-10

WOW!! again just an awesome account - you are very brave people - well done :-)