Our map shows us shooting across Lake Titicaca from the Isla del Sol to here. In theory it is possible to get a boat directly to Puno but in reality we went back by boat to Copacabana to collect our bags, stayed overnight and then took a bus across the border. Border formalities were very straightforward although we're not really clear how long we can stay in Peru. However that is not likely to be a problem and we shall try to avoid repeating our Paraguay troubles!

The centre of Puno is rather congested. It feels a bit as though the buildings have all slipped down the slopes surrounding the town and jumbled together a bit. The classic grid system is just a bit scew-wiff and many of the streets are not exactly square. Most are irregularly narrow with little or no pavements so you're forever stepping into the road and being beeped at by vehicles. The drivers here are very possesive of the road and tend to drive with one hand on the wheel and the other on the horn, despite many road signs imploring silencio.

The centre of town is also enlivened by the unfenced single track railway line which loops around to meet the lakeside. In reality this is not too much of a problem because trains are pretty infrequent and painfully slow when they come at all. Largely the populace ignore the tracks or use them as areas for impromptu parking or setting up stalls. It does have the interesting effect that vehicles might be travelling in either direction on either side of the track or even on occasions on the tracks themselves. Crossing the road is rarely easy here.

We have been doing the tourist thing and took excursions to save the hassle of organising our own trips. Our first vist was to the Chulpas (tombs) at nearby Sillustani. The tombs are beside Lake Umayo, a large lake which is actually higher than Titicaca (but of course it is smaller and too shallow for bigger craft).

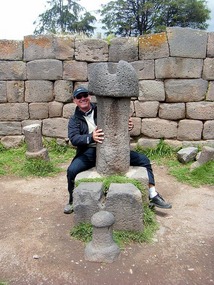

This spot was chosen because it is a summit and hence closer to the gods, it is also almost completely surrounded by the lake. The fact that many of the volcanic stones here are magnetic is an added bonus. The site has tombs of the most important Colla people dating back over a long period, vastly predating the Incas (the poor people are in unmarked graves on the next mountain). The earliest tombs are smaller and consist if holes covered and surrounded by cicles of rocks.

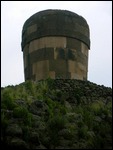

Over time, however, burial became more elaborate, requiring mummification and the addition of lots of grave goods. The tombs therefore became large circular above-ground rough stone burial chambers, each with a small 'door' to allow followers to continue to provide food and other requisites to the dead. When the Incas came, in their usual style, they absorbed the system of above ground burial towers but took it a good stage further by applying their ability to cut and dress stone to begin making larger and fancier towers (even trying out an innovative square tower).

However, their efforts came to very little as they had no sooner got into the swing of building their chulpas when the spanish came and spoiled the party completely. From our point of view it meant that some of the towers were left half built so we are able to understand the techniques they used to raise the towers. Over time lightning strikes have toppled many of the towers (and grave robbers have done their bit too) but what remains is still impressive.

The setting is beautiful and all around you can see the remnants of pre-inca terracing on the mountain slopes. In its heyday this must have been an inspiring sight and even now gives more than a little sense of awe and wonder. It was also the site of our first sighting of wild cuyo (guinea-pig). Of course these are also a local delicacy but we're staying veggie as much as possible so there'll be no reports of how they taste from us!

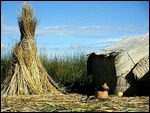

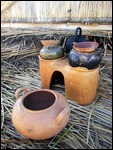

We also took a boat trip out onto the lake to visit two groups of people, each seeming to lead their old traditional ways of life (but one senses mostly while the tourists are watching). The Uros people were having a bit of a hard time being dominated by the Colla people so they devised an innovative way to get away from them. Going into the shallow parts of lake they cut away sections of the reeds with their root structure attached. When these are bound together they float and in this way they began to create floating islands, allowing them to float out into the lake and keep themselves to themselves.

It was successful to an extent but it was never going to be an easy life. When the Incas finally absorbed all the peoples of this area into their empire they imposed tithes related to the affluence of the tribes. So poor were the Uros people that they were only obliged to provide a bamboo stick filled with lice.

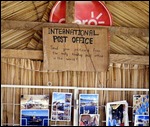

Actually, we really enjoyed our visit here. We were welcomed onto one of the islands and given a presentation of how the islands and houses are constructed. They said they didn't need money because they use barter systems to exchange stuff they have plenty of (like dried fish) with mainlanders who have stuff like maize and potatoes. This didn't, however, stop them from taking money for craftwork or charging us to go in their reed boat. There are not many people on each island, generally just an extended family. The leading forces on our island were a lovely young couple called Madeline and Leandro who took us into their house and showed us around (this was pretty quick as it was just one room, a double bed with roll out beds for their two kids). I asked if it was cold in winter but they assured us that it was warm enough provided you wear the right clothes.

They then dressed us up in traditional costumes (that they just happened to have around) and we all had a jolly good time, meeting the kids and talking about their life. We had read that many of the islanders actually live on the mainland now, coming out each day to meet the tourist boats. It is certainly true that each island has a lookout post to catch sight of approaching boats and the people come out with rehearsed routines to beckon the craft in. The island we were on and the people we met did not seem totally false. They pointed out thei children's school (on another floating island), were proud of their home and of new innovations such as the solar panel that allows them to have lights and watch TV.

Later, as we got into the reed boat to go across to another island, the women all gathered around to sing one of their traditional songs, which was actually very nice. They then drew on their repetoire of songs from other countries to sing a song for each nationality in our group. 'Alouetta' was an easy choice for a French girl and they even had a song for the two young Chinese girls. England stumped them for a bit but they came up with 'My Bonnie Lies Over The Oceon', so they were nearly right. As we finally left the side of the island, with a carefully choreographed flourish, the women called out 'Hasta La Vista, Baby'!

Our incredibly slow boat then took us on to a proper rock and dirt island called Taquile, where the local people proudly continue their tradition of 'weaving' (actually most of them were knitting). Maintaining traditions has been reinforced by the establishment of a cooperative for handwork and a fairly rigid social structure that places a premium on wearing traditional clothing. This means maintaining clothing very similar to that worn by the original Spanish invaders, with just a few Andean twists.

Thus, women wear black shawls, although unmarried women can have brightly coloured pom-poms hanging from them. Men wear a long knitted cap; mostly white for unmarried men but red once married. Important people (of course only men) wear a black hat on top of their cap. There's also a lot of mystique about the angle that hats are worn at and the side the tassle lies, indicating readiness to get married etc. There is no divorce on the island but couples are able to have a three year trial marriage.

Our guide seemed to indicate that this was a period which allowed both parties to ensure that they were both able to knit well. We’re not sure if this really did indicate a trial of how good their craft skills are or a euphemism for something else entirely.

If the trial doesn’t work out, the couple are free to split up although we also gathered that in these cases, someone may leave the island, never to return.

All over the island the local people sit around spinning, knitting or selling their goods. The cooperative insists that all similar goods are sold at the same price in every outlet so you soon begin to get a strong sense of dejá vu as you walk around.

There is a school on the island but that doesn’t seem to detain the children much who gather around every visitor pestering them to buy something. The town square was remarkably large and formal (after visiting Isla del Sol, we had expected a much more haphazard plan) with opposite sides dominated by a modern looking municipal building and the cooperative headquarters and shop.

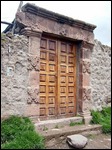

Interspersed were the normal adobe buildings but with a few stone details including some carved heads on features such as gates.

On our final full day in Puno we decided to visit the nearby town of Chucuito which has a couple of notable features. To get there we were going to take a collectivo (local bus) but when we got to the small local bus station there were strangely few signs of life. So we wandered further to where minivans leave. The first one we approached said that he wasn’t going to Chucuito because the roads were blocked, which confused us a bit further. We then spotted another nearly full minivan going our way so we piled on, along with about 15 other people and their luggage. These minivans don’t go until they are completely full, preferably with some more standing or hanging on the side. We finally got going and realised that the first driver was right, people had been placing rocks and glass in the roads to stop the traffic. In reality this is just an extra burden for the drivers, the roads being so potholed that every journey requires them to reroute, go of road and generally use their enginuity.

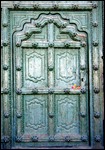

However, we managed the very bumpy ride (the driver having to use very back roads to get there) and found ourselves in a strangely expansive small town. The main plaza was huge with a very impressive old church. Great care had obviously been taken by the parks department; the trees and bushes were mostly snipped into strange shapes of creatures including people, birds and animals.

The square also holds a sundail, reputedly erected by the spanish in a desperate attempt to get the local people to conform to some sort of working day. Walking a short way from the main square we were surprised to find ourselves in another attractive square almost as big as the first.

This one was dominated by another very old church which had sadly suffered a roof collapse a few years ago. Although it has now been restored, the wall paintings which had previously covered all the walls and the soaring dome have been destroyed. All that remains is a small section over one of the arches to give a tantalising glimpse into lost glories.

This church stands next to our ultimate destination, the so-called Temple of Fertility. Inside a substantial Incan wall stand a large number of phallic objects set out in ranks around a few larger and more detailed ones. We had a very interesting chat with the caretaker of the neighbouring church who advanced some interesting ideas questioning the basic premise that it was an Inca temple.

The wall is clearly Inca and precise enough to be associated with a religious site. However, he said, no evidence of offerings or fragments of other materials (pottery, metal etc) have ever been found around the site, suggesting that it wasn’t really used. He also pointed out that there are no other examples of such temples anywhere else in the Inca empire. He even hinted that the objects may originally have been something else entirely but because they resembled willies they have been asembled this way as a tourist attraction.

Who knows - but it gave us a bit of a laugh!

We caught a returning minivan and, after a bite of lunch, headed in the opposite direction to visit the Yavarí, the first steamship on Lake Titicaca. It and its sistership were ordered from England in the 1860s and shipped in 2766 parts to Arica (now in Chile but then in Peru).

The next stage of the journey was to carry the parts across the Andes (at this stage there were no roads or rails so this had to be done using llamas). The contractor for this stage estimated six months for the job but actually it took six years, the boat finally being assembled and launched in 1870. However, because there was no coal, the engine had to be fired by llama dung. But llama dung takes up more room than coal so the boat had to be extended and the cargo holds used to carry the llama dung to power the boat. Finally in 1910 it had a swedish marine engine fitted and survived a chequered and declining career until taken over by a non-profit company to restore it.

Luckily many of the fixtures and fittings that had been stripped from her were in local museums and could be reclaimed and Volvo restored the engine (it is now the oldest working engine of its type).

But it has been a long job; we watched clip from Michael Palin’s 'Full Circle' series where they were talking about it being finished "soon" but that was probably in the mid 1980’s. They now have a sea-worthy certificate but cannot carry passengers because the deck is too uneven and there are insufficient bulkheads. However they are planning to open the boat as a B&B “soon”!

As we headed back to our hotel we were aware that the number of road blocks was increasing on all the roads into and out of Puno, the demonstrators were obviously getting more determined. Let’s hope that we are able to get our bus out of town and on to Cuzco tomorrow morning!

Incas, Pre-incas and a load of willies.

Friday, March 05, 2010

Puno, Puno, Peru

Puno, Puno, Peru

Other Entries

-

71Multicoloured mountains and angels with guns!

Dec 2768 days prior Humahuaca, Argentinaphoto_camera53videocam 0comment 1

Humahuaca, Argentinaphoto_camera53videocam 0comment 1 -

72Following the Train To The Clouds

Dec 2966 days prior San Antonio de los Cobres, Argentinaphoto_camera81videocam 0comment 0

San Antonio de los Cobres, Argentinaphoto_camera81videocam 0comment 0 -

73Cafayate; days of wine, icecream and waterways

Jan 0262 days prior Cafayate, Argentinaphoto_camera42videocam 0comment 3

Cafayate, Argentinaphoto_camera42videocam 0comment 3 -

74Tucumán; chilling out and getting heated!

Jan 0559 days prior San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentinaphoto_camera26videocam 0comment 1

San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentinaphoto_camera26videocam 0comment 1 -

75Like Birmingham but better!

Jan 1054 days prior Córdoba, Argentinaphoto_camera64videocam 0comment 2

Córdoba, Argentinaphoto_camera64videocam 0comment 2 -

76Wines, Bikes, Barnsley and Bernard O'Higgins

Jan 1648 days prior Mendoza, Argentinaphoto_camera45videocam 1comment 1

Mendoza, Argentinaphoto_camera45videocam 1comment 1 -

77Over the Andes to Santiago

Jan 2341 days prior Santiago, Chilephoto_camera95videocam 0comment 8

Santiago, Chilephoto_camera95videocam 0comment 8 -

78Carnival Time in Paradise Valley!

Jan 2737 days prior Valparaíso, Chilephoto_camera89videocam 0comment 6

Valparaíso, Chilephoto_camera89videocam 0comment 6 -

79City of churches, craft stalls and penguins!

Jan 3133 days prior La Serena, Chilephoto_camera55videocam 1comment 1

La Serena, Chilephoto_camera55videocam 1comment 1 -

80More Marys than you can shake a skull stick at.

Feb 0627 days prior San Pedro de Atacama, Chilephoto_camera91videocam 3comment 1

San Pedro de Atacama, Chilephoto_camera91videocam 3comment 1 -

81Mountains, lakes, salt plains & altitude sickness

Feb 0825 days prior Uyuni, Boliviaphoto_camera82videocam 1comment 5

Uyuni, Boliviaphoto_camera82videocam 1comment 5 -

82Dead people, dead trains and dead electrics!

Feb 1023 days prior Uyuni, Boliviaphoto_camera30videocam 0comment 3

Uyuni, Boliviaphoto_camera30videocam 0comment 3 -

83Let the festivities begin (but not in the convent)

Feb 1320 days prior Potosi, Boliviaphoto_camera78videocam 0comment 0

Potosi, Boliviaphoto_camera78videocam 0comment 0 -

84No sugar but lots of water and... dinosaurs!

Feb 1914 days prior Sucre, Boliviaphoto_camera61videocam 0comment 5

Sucre, Boliviaphoto_camera61videocam 0comment 5 -

85Possibly the highest capital city in the world...

Feb 2310 days prior La Paz, Boliviaphoto_camera89videocam 1comment 4

La Paz, Boliviaphoto_camera89videocam 1comment 4 -

86Shining Lake Titicaca (when it isn't raining).

Feb 267 days prior Copacabana, Boliviaphoto_camera47videocam 1comment 2

Copacabana, Boliviaphoto_camera47videocam 1comment 2 -

87Despite the name, it's not always sunny here!

Feb 285 days prior Isla del Sol, Boliviaphoto_camera51videocam 0comment 0

Isla del Sol, Boliviaphoto_camera51videocam 0comment 0 -

88Incas, Pre-incas and a load of willies.

Mar 05 Puno, Peruphoto_camera113videocam 0comment 0

Puno, Peruphoto_camera113videocam 0comment 0 -

89Road blocks, demos and a scenic journey to Cusco

Mar 061 day later Cusco, Peruphoto_camera76videocam 0comment 5

Cusco, Peruphoto_camera76videocam 0comment 5 -

90Touring the Sacred Valley

Mar 072 days later Ollantaytambo, Peruphoto_camera50videocam 0comment 8

Ollantaytambo, Peruphoto_camera50videocam 0comment 8 -

91Visiting the Inca sites around the city.

Mar 094 days later Cusco, Peruphoto_camera46videocam 0comment 3

Cusco, Peruphoto_camera46videocam 0comment 3 -

92The White City

Mar 1611 days later Arequipa, Peruphoto_camera92videocam 0comment 2

Arequipa, Peruphoto_camera92videocam 0comment 2 -

93Strange markings at Dead Bull!

Mar 2318 days later Toro Muerto, Peruphoto_camera32videocam 0comment 0

Toro Muerto, Peruphoto_camera32videocam 0comment 0 -

94Colca Canyon 1: Snow and the Ice Maiden

Mar 2520 days later Chivay, Peruphoto_camera17videocam 0comment 2

Chivay, Peruphoto_camera17videocam 0comment 2 -

95Colca Canyon 2: Watch out, condors about!

Mar 2722 days later Cabanaconde, Peruphoto_camera56videocam 1comment 1

Cabanaconde, Peruphoto_camera56videocam 1comment 1 -

96Colca Canyon 3: Hot and Passionate

Mar 2823 days later Arequipa, Peruphoto_camera21videocam 0comment 0

Arequipa, Peruphoto_camera21videocam 0comment 0 -

97More lines and symbols but this time they're BIG!

Mar 3126 days later Nazca, Peruphoto_camera41videocam 0comment 2

Nazca, Peruphoto_camera41videocam 0comment 2 -

98Sun worshipping through the years

Apr 0430 days later Trujillo, Peruphoto_camera62videocam 0comment 2

Trujillo, Peruphoto_camera62videocam 0comment 2 -

99We go in search of GOLD!

Apr 0733 days later Chiclayo, Peruphoto_camera58videocam 0comment 4

Chiclayo, Peruphoto_camera58videocam 0comment 4 -

100Sun, surf and a very loud children's fairground

Apr 1137 days later Máncora, Peruphoto_camera22videocam 0comment 3

Máncora, Peruphoto_camera22videocam 0comment 3 -

101In search of exotic animals: we find iguanas

Apr 1339 days later Guayaquil, Ecuadorphoto_camera21videocam 0comment 1

Guayaquil, Ecuadorphoto_camera21videocam 0comment 1 -

102We arrive and dive.

Apr 1642 days later Puerto Ayora, Ecuadorphoto_camera64videocam 2comment 1

Puerto Ayora, Ecuadorphoto_camera64videocam 2comment 1 -

103We set sail, eventually.

Apr 1743 days later Bartoleme, Ecuadorphoto_camera46videocam 0comment 4

Bartoleme, Ecuadorphoto_camera46videocam 0comment 4 -

104Iguanas in all their many forms.

Apr 1844 days later Santa Fe Island, Ecuadorphoto_camera32videocam 0comment 3

Santa Fe Island, Ecuadorphoto_camera32videocam 0comment 3 -

105Not all the animals here are friendly.

Apr 1945 days later San Cristobal, Ecuadorphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 1

San Cristobal, Ecuadorphoto_camera8videocam 0comment 1 -

106Albatross, fresh albatross!

Apr 2046 days later Espanola, Ecuadorphoto_camera29videocam 0comment 1

Espanola, Ecuadorphoto_camera29videocam 0comment 1

Puno, Puno, Peru

Puno, Puno, Peru

2025-05-22