If you like variety in beer, Belgium is the place for you.

Other countries like Germany, Britain, and Czech Republic are known for their

beer too and probably produce and consume a similar amount per capita, but

Belgium has more variety of styles and flavors than any other country. That’s

especially true on a per square mile basis since the small country now has

about 250 active breweries.

Obviously it’s not possible to try them all in a month in

the country, but I made an attempt to try as many different ones as I could

rather than drinking the same ones over again. Of course, with so much to

choose from I sometimes lost track and ordered one I had already tried.

Averaging a few beers a day, though, I got to try a good variety over my month

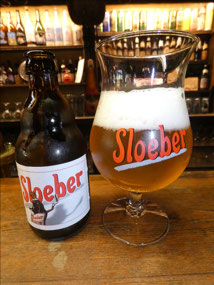

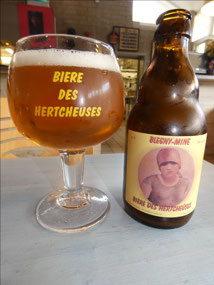

in the country. I decided to take pictures of all my conquests for a beer diary

entry in my blog.

Additionally, almost every beer in Belgium comes in its own

specially designed glass that’s supposed to help bring out its unique flavor.

Where does a bar or restaurant store all those glasses when they typically

offer a huge variety of bottled beers as well as a fair selection of drafts?

They’re usually all over the place, often hanging over the bar.

Belgians seem very traditional in their choice of beverages

with beer predominating as a drink to sip outside or in a café, have late at

night, or drink with a meal. In some other traditionally beer-drinking

countries like Germany, Netherlands, and Britain, wine and mixed drinks seem to

have caught on more, especially with the hipper set and (wine) as an

accompaniment for meals.

You can, of course, get those in most bars and

restaurants in Belgium, but you don’t see that many people drinking them. And

while Flemish and Walloon people may speak different languages and disagree

over politics, beer is a uniting constant throughout the country. They may

speak French in Wallonia, but that doesn’t mean they grow grapes or prefer to

drink wine instead of beer.

Although it’s difficult to imagine, I’ve met people who

actually don’t like Belgian beer, or at least they don’t like most of the

different and unusual styles because they’ve learned to drink only Pilsners or

Ales. This seems to be more true of British and Antipodeans than North Americans

who have become accustomed to the variety available nowadays at microbreweries.

And it is true that some kinds of Belgian beer are either very potent

alcoholically or have flavors that many would not normally associate with beer.

There are a number of reasons behind the wide variety of

flavors in Belgian beer. One of those is different fermentation methods, difference

in processes that have been described to me numerous times on brewery tours that

goes way over my head and never makes it clear which type of fermentation

produces what flavors. The other is a variety of ingredients. Belgium doesn’t

have Germany’s so-called beer purity laws which only allow four ingredients to

be used. Thus, beer can be brewed with interesting spices, fruits, and other

ingredients. I am a little more up on the different styles of Belgian beer,

almost all of which I sampled during my trip.

Most beer produced and drunk in Belgium is the standard

Pilsner (just called Pils) or Pale Lager that is the definition of beer in most

of the world. The best known and most widely exported one is Stella Artois, but

Jupiler, Maes Pils, and Cristal are other top brands. To be honest, they’re

pretty standard and not all that special, pretty much the kind of beer you’d

drink at an outdoor festival, at a football/soccer game, or slumming it at a

cheap dive bar. I tried several of them while I was in Belgium, generally more

on hot days when I was in the mood for volume rather than flavor and alcoholic

buzz.

One of the most famous type of Belgian beer is Trappist

beer, which is more of a designation rather than a style. Trappist certified beer

must be produced in a monastery, made by actual monks, with profits going to

support the monastery or other social programs. Only six monasteries in Belgium

(and five in other countries) meet those qualifications. They are Westvleteren,

Westmalle, Rochefort, Orval, Chimay, and Achel. I tried beers from all of them

while in Belgium and visited two of the monasteries (Westvleteren and Orval). Although

you can’t actually see the monks at work at any of the, they do run cafes where

you can try their product as well as have some food, in some cases cheeses that

are also made by the monks. Westvleteren

is considered by some to produce the world’s finest beer, one of its outputs

effectively rationed in that its sold only at the monastery store, has to be

ordered in advance, and not more than a case can be purchased at a time.

Next there’s Abbey beers, a much broader designation which includes

beers made in the monastic or abbey styles either by a non-trappist abbey, a

commercial brewer in conjunction with an abbey, or using the name of a defunct

abbey. There are 18 designated abbey breweries in Belgium, most of which produce

beers in a couple recognized styles. Among those whose output I tried were

Affligem, Abbaye Val-Dieu, Ename, Floreffe, Grimbergen, Leffe, Maredsous, and Steenbrugge.

Some of the traditional abbey beers are now produced by the bigger brewing companies.

Another famous style of Belgian beer is Witbier (Blanche in

French), or white beer which is also wheat beer. Before hops were used in beer

it was flavored with what’s known as gruut, a mix of spices that helps give it

it’s unique flavor. A couple of the most ones I tried include Hoegaarden,

Blanche de Namur, at Watou Wit.

Blonde or Golden Ales are another popular style of beer in

Belgium. I find them to be quite a lot like many of the microbrewery ales in

America, but what’s notable about them in Belgium is that they are very strong,

typically around 8% alcohol. Duvel is one of the most famous such ales, but

there are many others with names suggesting evil or strength.

One of the most unusual types of beers in Belgium is Lambic

and its affiliated Gueuze and Fruit Lambic styles. What names Lambic unique is

that it comes only from one region, Brussels and the Pajottenland to the city’s

southwest, and is fermented by naturally occurring wild yeasts in the air in

the Senne Valley rather than added strains of yeast.

As well as other unique

processes, the beer undergoes a long aging period which gives it a very dry,

rather cidery and sour flavor. A Gueuze beer is a blend of old and young

lambics that undergoes an additional fermentation for a unique flavor. Lambics are sometimes also flavored with

fruit. These beers tend to be low in alcohol and on the expensive side.

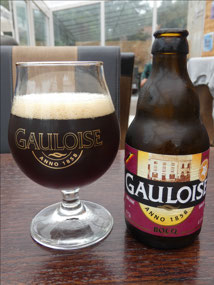

Next we have Amber Ales that are similar to American pale

ales, usually a little darker in color and not too high in alcohol like Antwerp’s

De Koninck and also Dubuisson and La Gauloise. A few of the festival beers I

had like La Gouyasse and Goliath in Ath also were in this style.

Many Belgian beers, both abbey beers and others, are

characterized at dubbel, tripel, and even quadrupel, although they are usually

only called that (rather than abbey) if they are not affiliated with an abbey.

These are amber to dark ales that are brewed with extra amounts of grain malt

that increases their potential alcoholic strength – think beers in the 7.5% to

10% alcohol range, sometimes even 11%. Potent!

Your bottle of beer is equivalent to two regular horse-piss pils beers.

Keep that in mind if you’re going to have to drive anywhere soon.

Flemish Red and Flemish Sour Brown ales are two similar

styles of beer typical of the West Flanders, my mother’s part of the

country. They have unique production

processes which give them their flavor which in some cases includes oak-barrel

aging. Rodenbach from Rousselare is the most famous of this style of beer, but

another is Bourgogne de Flandres, literally “Flanders Burgundy”.

Where else in

the world do they age beer in oak casks like fine red wines? Probably nowhere.

Finally, there’s Saison beers, typical of Wallonia and considered

a summer drink because of their generally low-alcohol contents that were

originally brewed on farms to fortify workers during the harvest season. They’ve

really caught on with microbrewers in America.

I had a couple beers in Belgium that are now produced there

but are not traditional styles of the country but imports from elsewhere. Hey, just because they didn’t make a type of

beer in Belgium ages ago doesn’t mean they can’t make them nowadays. Among

those are Bock (Germany), Stout (Ireland), Scotch Ale (Scotland), a high-hopped

beers like IPAs (England).

Having a limited amount of time to blog while traveling I

left a few entries to complete when I got home after the end of my trip. My

beer diary entry was my last one since I couldn’t make a decision about how to

arrange the pictures in my diary. Should it be chronological, by beer type, by

province of production, or by place I drank the beer. I decided to leave them in mostly chronological

order and just mention style and origin town for all.

Brussels, Brussels, Belgium

Brussels, Brussels, Belgium

2025-05-22