Willie Gordon & "Gangurru" carnage

Friday, October 31, 2014

Cooktown, Queensland, Australia

Cooktown, Queensland, Australia

Cooktown lies about four hours north of Kuranda by road. It is of major historic significance to Australia and the aboriginal community. Definitely wanted to visit.

We left one morning and travelled north on a good sealed (paved) road almost devoid of traffic. As we left the Atherton Tableland and travelled further north, the forest changed – trees became smaller and spaced further apart. We started to travel through cattle country with plenty of signs warning of cattle on the road.

Cattle raised here are a special Brahma breed that can tolerate heat and poor grazing, yet put on the weight when times are good. We arrived at the tail end of the dry season and pasture was extremely poor. The cattle we saw around small waterholes were thin and ranchers were providing feed to carry them through to the wet season. As in many parts of the world, climate change is happening here and residents told us the rainy season has become less predictable as to time of arrival, length, intensity and amount of rainfall.

As we travelled, we noted that the odd wallaby and kangaroo were among the road kill. However, we entered a stretch of highway where the carnage was horrific. Wallaby corpses, old and newly killed, littered the roadside. Black kites, the equivalent of our vultures, circled overhead and descended to feast both on the road kill and the odd dead cow near the road. Given the number of dead animals we saw in just one morning, it was hard to imagine that any wallabies would survive in this stretch of country.

Seeing the carnage brought home to us why virtually all trucks and most large SUVs had serious metal grill protectors. It also became clear why when buying vehicle insurance in Australia you have to read the fine print. Many insurers do not provide coverage for night driving or large animal/kangaroo collisions unless special coverage is purchased.

We reached Cooktown in the early afternoon and located a place to eat lunch at the local botanic gardens, one of the oldest in Australia. While eating we noticed a lone Red Kangaroo foraging at a distance. It is fascinating to watch these large animals dexterously using their front limbs as arms and "hands" to dig, gather vegetation and to push other kangaroos and wallabies around if need be. What was really intriguing is how fast and how much distance this kangaroo could cover when it decided to move along at speed. You have to wonder about how a creature that hops to get around ever got to be so large and agile and the dominant indigenous grazing animal in Australia.

We dropped into the visitor centre, called Nature's Powerhouse, which also doubles as an environmental education facility, interpretive centre, information outlet and art gallery. The exhibits were very well done and focussed on a theme rarely covered in detail – poisonous snakes! This exhibit was funded by a snake venom researcher whose work helped in the development of anti-venoms. I walked away with a new respect for the taipan, a large and the most deadly poisonous snake in Australia. It feeds solely on mammals (mostly bandicoots and rats) and has evolved toxins that act very quickly by affecting the nervous system and by clotting the victim's blood. It also strikes with great speed and accuracy; that combined with a mean and cantankerous personality have justifiably earned it a lot of respect. The display told the story of the only known survivor of a taipan bite who was not treated with anti-venom. He was pronounced dead a number of times during his recovery period but managed to pull through probably because he was in great physical shape.

In the same building was a gallery of paintings by a local painter,Vera Scarth-Johnson. Vera painted local plants with the aesthetic sensibilities of an artist and the accuracy of a scientific illustrator. I lingered in this gallery a long time because I was able to put names to some of the plants I saw in our walks and travels and because the gallery also displayed a set of collectors’ copies of paintings that were produced by botanists and illustrators, some of whom accompanied James Cook when he sailed to Australia in 1770.

A surprisingly impressive museum in this small town was the James Cook Museum. Housed in an old convent, the museum featured an anchor and cannon that Captain Cook’s crew threw overboard to keep from sinking when his ship Endeavor hit a coral reef near to present day Cooktown. The displays also explained with artefacts, illustrations and log entries by Cook and some of scientists that accompanied him how the Endeavor after hitting the reef limped into the mouth of the nearby river, which Cook named the Endeavor, and was grounded on shore for seven weeks while repairs were made. This time was used by the scientists to gather plant specimens and make observations. There was even the tree Cook tied Endeavor to while repairs ongoing. mmmm

The most fascinating part of the display for me dealt with how Cook perceived the Aborigines and how they perceived Cook’s arrival. A real clash of cultures as notes from his log book were put up side by side with the observations and comments obtained from Aborigine elders about this encounter with Cook. Long story short, if it were not for some hesitancy on the part of the natives (because he and his crew were white, the Aborigines thought these strange beings may have been the ghosts of their ancestors) and great diplomacy on both sides, Cook would likely have been massacred in Australia and perhaps the history of the country and the Aborigines would be quite different today.

That evening Sher and I climbed Grassy Hill, a height of land overlooking present day Cooktown. James Cook stood on this very hill in 1770 and searched for a way out of the coral reefs that holed his ship. It must have been a daunting experience for him because through his telescope he would have seen breakers in the far distance and no clear passage out. He did find one eventually and made his way back to England.

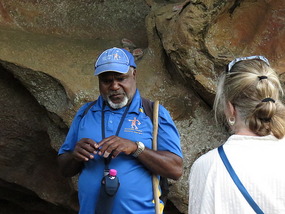

The following day we went to meet Willie Gordon. He is of the Nugal clan of the Guugu Yimithirr tribe. His clan along with thirteen others have legal stewardship over 110,000 hectares of land northwest of Cooktown. Willie has a tour company (Guurrbi – roughly translated as "place for reflection") and takes guided tours through the lands of his clan. Four of us were booked for the morning tour but the other couple did not show so Sher and I had a private five hour tour.

What a special experience! First of, Willie is a quiet but powerful personality with a playful sense of humour and a twinkle in his eye. He has been shaped by some difficult times, alcoholism, drugs and contemplation of suicide. He survived all that to become a deeply moving story teller, curator and bridge builder for the aspirations of his people.

He guided us through a thinly treed landscape to a series of natural rock formations and overhangs within his clan’s land. Along the way he showed us the natural land marks that form the boundaries of Nugal clan territory and told us some of the stories that date back to Dreamtime (the time when all things were brought into being on this earth) about the formation of the landmarks. He also showed us items that were used for bush tucker (food) and medicines. When he found the leaf nest of green ants he let some swarm over his hands then rubbed them together crushing the ants. He asked us to inhale from his cupped hands. The strong smell of formic acid that we inhaled was used to clear congested sinuses. He knocked over a number of thick stems of a plant with grass-like leaves and explained that the large, fat, protein-rich witchity grubs burrow into these stems and in season were a food source to add protein to the diet. Another Aborigine we met described eating the grubs was like eating a mixture of sawdust and fatty meat, definitely an acquired taste.

We then arrived at the first of the overhangs that protected rock paintings. Willie explained, “The cave paintings, left to us by our ancestors, represent a path through life. For us to be able to walk these paths is to renew our historical and spiritual links with the land. It reminds us who we are and gives us the strength to move toward the future.” Some of the paintings are very ancient, while others are less than 100 years old. Willie’s grandfather contributed to some of the paintings and the interpretation of their meaning, the stories they tell, were passed on to Willie’s father and from him to Willie.

As we travelled about Queensland Sher and I encountered interpretive panels talking about the Rainbow Serpent and here in these overhangs we saw paintings of it. Willie explained, “Rainbow Serpent is the symbol of the Creator. A flowing river, carrying life-giving water has the shape of a serpent; and the rainbow is what happens when light and water come together – the two vital elements which sustain life on earth. When you see a rainbow it should remind you of the creation.”

Hand stencils were a common theme under another overhang. These are made by first painting the rock with a wash of red paint made from ochre. The person making the hand print places their left hand (the peaceful hand) on the red wall then sprays the white ochre over the hand using a hollow bone, leaving a red hand print outlined in white. Hand stenciling was often done to symbolize the initiation of a new family member into the clan.

Another painting depicted what looked like a cocoon covered with horizontal and vertical lines widely spaced. Willie explained that this drawing informed people that the bones of an ancestor were nearby encased in a bark wrapping bound with cords and tucked into a cave or deep crevice in a rock wall. In this case they were the bones of Willie’s grandfather.

Another figure depicted a male figure with distinct lines across his chest. This was the figure of a specialist in some form of knowledge – healing, crocodile hunting, tool making, communicating with other tribes. The lines were earned as the person gained status and reputation. The lines were actually cut into the chest of the living person. The procedure consisted of giving the person a strong pain killing drug. Then a razor sharp piece of rock was used to make the incisions through the skin. Into the incision was rubbed white clay or other material to ensure the wound would heal leaving a large raised scar. Pictures taken of Aborigines in the late 1800s distinctly show these marks on men’s chests.

One of the most powerful paintings we saw was in the birthing “cave”, a large space protected by a rock overhang. From a distance the overhanging rock looks like the head of the Rainbow Serpent (often represented by a python) a strong spiritual symbol of creation. The painting was of a woman giving birth and consisted of the mother, newborn and father.

But the father was painted upside down symbolizing that he had little influence or control over the birthing. This may have been the most important stop on the tour for in this location the Nugal clan believes each new baby coming into the clan is born not only in body but in spirit. Understanding that this is a critical time for the newborn and the clan a powerful protector spirit is painted above mother to help ensure the baby would grow into a strong supportive member of the clan. Willie’s father was born in this birthing cave.

[

The panel of paintings before the birthing panel were instructions for the mother to be, to ensure she was having the baby for all the right reasons. The paintings included powerful symbols that would protect her but also a negative symbol that showed things could go wrong and that she must prepare herself for this.

The final stop was in an overhang that sheltered a set of Stone Age tools. The axes, scrapers and stone knives looked similar to many we’ve seen in museums. Only this set was in use by Willie’s father until the 1930s when he “came out of the bush”. What a cultural dislocation Willie must be experiencing bridging the Stone Age with the space age. He chuckles about this as he pulls out his cell phone and makes a call, an indispensible tool of his life in the 21st century.

Willie told us one other story. When Captain James Cook was repairing his ship in 1770 the aborigines he encountered were Willie’s ancestors the Guugu Yimithirr. Willie said, “I guess that Englishman just didn’t have the ear for our language because when asked what do you call the large animal that hops about, he was told “gangurru”. He recorded it as “kangaroo” and that is how it is to this day. In some literature and interpretive centers in northern Queensland the spelling gangurru is still in common usage.

Other Entries

Cooktown, Queensland, Australia

Cooktown, Queensland, Australia

2025-05-23