Headed out of Los Alamos toute de suite this morning; definitely time to get out of the twilight zone. We were not going far today: just to Valles Caldera National Preserve, which is up in the mountains about 25 miles to the west. To get there, though, you have to drive right through the Los Alamos Lab complex, which means that you have to go through a security gate and show your ID and be warned to drive straight through and take no photos. I have no idea what work they are doing there these days, and, of course, that is the point. I'm not supposed to have.

To get to Valles Caldera, you drive right over Pajarito Mountain, up to about 9000 feet. The air up there is not as noticably thin as, say, the top of Pike's Peak (14,000+), but it's thin enough to notice. As you come down the western side of the mountain, you get spectacular views of the Valle Grande, the valley formed by the caldera. I took many more photos than I posted, and the photos don't do it justice, because a photo just cannot capture the scale of the place, but you should get a good sense from the photos of what the terrain is like--it is truly spectacular.

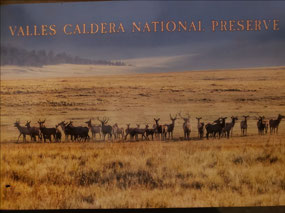

The Valle Grande is approximately 7 miles long and 3 miles wide and is surrounded by pine-covered mountains.

The preserve encompasses about 89,000 acres of what began as a 100,000 land grant in the late 19th century. The landscape, however, is much older--it formed about 1.25 million years ago in a massive volcanic eruption. The eruption created the caldera, a sunken valley surrounded by mountains. The valley is too wet for the pine trees that cover the surrounding hills and mountains, leaving the striking wide open space we have now. The valley is home to a large herd of elk. We saw some elk, but from far, far away, so that they look like little brown blobs, even with my excellent zoom lens zoomed all the way in.

We saw a lot of other wildlife, though: Gunnison Prairie Dogs (in large numbers), an Eastern Chipmunk, some Mountain Bluebirds, a juvenile Red-Tailed Hawk (which had killed a prairie dog--I didn't get a photo of him when he flew off with his lunch, alas!), and several kinds of butterflies, some of which were new to us.

We also saw a Long-Tailed Weasel--also a first! Explanations on photos.

We arrived at the park just in time to join the 11 a.m. tour of the cabin area. A ranger took us around to see a number of historic cabins, dating back to 1915 and the earliest owners of the land. The tour brings us all the way up through the history of the place to the present day. Explanations in the photo captions. One of the highlights of the cabin area (and so the guided walking tour) is the cabin which was used in the filming of Longmire as Longmire's cabin. Apparently quite a few people come to the park solely to see the cabin. It is located in a really beautiful spot--I could certainly be talked into waking up to that view every morning. (Of course, since there is no running water and no electricity, I imagine I would get tired of the cabin very fast, though not of the view!)

This next section is a lengthy description of the chequered history of this land. If you're not interested, skip down to the ************* or to the photos.

Private ownership of this land began in about 1876, when 100,000 acres were granted to the Luis Maria Cabeza de Baca.

There don't seem to be any shenanigans associated with his family's ownership of the land. He sold it in 1899 to Mariano Otero, and it was with the Otero family that trials and tribulations began. According to the ranger, a large number of members of the Otero family held the property jointly, in shares. Then some of the members of the family started selling their shares off to people outside the family. Eventually, the Oteros owned less than 50%. At that point, all the other shareholders decided they didn't want to be part of holding the land jointly; they wanted the parcel carved up and distributed equally. This proposal went to court, and a judge ruled that given the hugely diverse geography of the 100,000 acres, there was no way to divide it up evenly. He ordered that an auction be held. The winner would own the whole piece of land, and everyone else would split the proceeds. The Oteros lost the auction and so their hold on the land.

The new owner sold more or less immediately to the Redondo Logging company.

Apparently the owners of the logging company did not realize that it wasn't feasible or cost-effective to log the country at that time, as there was no infrastructure. They sold the land in 1918 to a local rancher, Frank Bond, who wanted to run sheep there. In the deal, however, Redondo retained the logging rights and half the mineral rights for 99 years. You can just see this becoming a problem down the road....

The Bonds ran the land until 1962, but it was not a happy time in the history of this valley. They ran what is called a partidario, which is essentially sharecropping for sheepherders. The Bonds set up a commisary from which the sheepherders bought their supplies, but this was a system slanted heavily toward the Bonds, who owned a mercantile and so were selling their own stuff to the sheepherders, who basically handed over everything they earned to the Bonds either in the lease fees (in the form of sheep and wool) or at the commisary. Think of the company stores at mining companies, and you get the picture.

Over the course of this period in the park's history, Bond ran 30,000 sheep here and overgrazed the valley to the point that the watershed was damaged and has not yet fully recovered.

The Bonds sold the land in 1963 to the man who would be the last private owner of the property: Pat Dunigan, and oil magnate from Texas. This worried locals, who feared the whole thing would be torn up in drilling, but Dunigan loved the country and set out to protect and preserve it. He cut the grazing way back (or maybe out, not clear), but no sooner did Dunigan take up residence (or at least ownership) than those logging rights reared their ugly heads. Redondo decided that it was now economically feasible to log in this area. I don't really understand why, as they had to build all the logging roads (the roads that are there now are those which were built for logging), and the ranger did not make it clear as to why this could be done in 1963 but not in 1918. They went in and started a massive clear-cutting effort which was tearing up the land and removing vast quantities of old growth Douglas Fir and and Ponderosa Pine.

Dunigan took them to court over it and lost. (I am not sure why the logging rights should give Redondo the right to tear up the property owned by someone else, but that's what the courts decided.) Dunigan, fortunately for all of us, was rich enough to buy the logging rights back from Redondo, which he did, and then he began working on restoration and erosion control.

Dunigan wanted the land to become a national park site; however, locals didn't want it to go to the federal government, and a compromise deal was struck by which a Trust was created to oversee the land. President Clinton signed the legislation in 2000, creating the Valles Caldera Trust. The trust was given the task of making the land financially self-sustaining by 2015. This never happened and efforts began again to sell the land to the National Park Service. Barack Obama signed the 2015 National Defense Authorization Act in December of 2014, and attached to that legislation was a rider granting authority of the Valles Caldera was transferred from the (failed) trust to the National Park Service, which has run it since October 2015.

I found it to be quite interesting that there has been so much drama involved in the historyof this incredibly beautiful piece of land over the course of more than 100 years and six different owners.

One other side note: the ranger, Topher, did a good job of the tour, but she didn't seem to know anything else about anything related to the nature or geography of the area. She didn't know anything about the trees or other plants, she didn't know anything about birds, and she didn't know anything about the mammals (except she did know what a prairie dog is). We often run into some of this at NPS sites: I don't think we've ever found anyone who knew anything about butterflies, and we have only found someone who knows about the birds in the area a few times. But generally the rangers know something about the trees and plants in the area. We were hoping that we could ask the other ranger, a grizzled old dude who looked like he had been around awhile, when we got back down from the cabin area to the main visitor center, but, alas, Topher and the grizzled guy had switched places by the time we got down there, and so we had to ask Topher, without much hope, what kind of weaser was living under the porch of the visitor center.

She didn't know.

I tihnk it's very curious that someone who actually works in a park apparently has so little natural curiosity. Never mind that, as a ranger, you are going to get questions from the public (and I would think it would get to be quite embarrassing to constantly say "I don't know"), but I would expect someone who works there every day to wonder about stuff she sees. We saw what turned out to be two Long-Tailed Weasels as soon as we got out of the car at the visitor center. If we saw them that quick, the rangers, who are there all day ever day, must see them regularly--especially as they live under the porch. Wouldn't you ask the other rangers: "What's that little animal that lives under the porch?" just because you wanted to know for yourself??? I would. I did! I had to look it up myself on the Internet. Fortunately, the little critter, which we have never seen before, was easily identified. Photo appended.

*************************

We knew that there would be no services out at the park, so we bought Subway sandwiches before leaving Los Alamos, and, after the walking tour, we ate a very enjoyable lunch overlooking the Valle Grande, before taking a walk down toward the historic pine grove--one which was not logged, and so has trees as old as several hundred years.

This park is not easy to get to, but it is very beautiful and well worth the trouble. I can recommend it highly--this must be one of the most beautiful spots in the United States. Up there with Yosemite.

When we left the park, we headed to Cuba, NM, the nearest town where Tim could find a hotel. In fact, there are three. There are also three remaining Mexican restaurants, a taco truck, a drive-through Chicken/BBQ place, a McDonald's and a Subway. The Mexican restaurants, it turned out, closed early: two at 6 and one at 6:30--on a Saturday! That left us with the chicken place which was advertised as being open until 8, but when we got there, was down to very little food (a few boxes of fried chicken), and the store closed by 7 while we were sitting outside eating. We were thinking that there were really slim pickins here, until we looked up the population of Cuba, which is 793 (up from 731 in 2010 and 590 in 2000). Believe it or not, the burg is growing. I no longer think there are a surprisingly few choices; now I realize that there is a surprisingly large choice--both of hotels and of restaurants. Bandolier NP is over near the Valles Caldera, and we guess that those two parks draw enough to keep Cuba in business.

Cuba has a pretty interesting history dating back to 1736. It was long a ranching and farming community, but eventually suffered from really dreadful overgrazing. You can read about the history of the town here; I recommend it!

Valles Caldera, New Mexico, United States

Valles Caldera, New Mexico, United States

2025-05-22