Our First Meeting with Igor, Tatiana, Yashka and His Family

I expect it sounds somewhat unusual that we met and fell in love with a pet reindeer on our first visit to Pevek in March 2018. After all, tough Pevek people like our Chukchi friend Igor come from generations of herders and most of their diet is reindeer meat. But the adorable orphaned baby Yashka was part of Igor and Tatiana's family and lived with them and their three Siberian Huskies at an apartment building right in Pevek town. Yes, actually in an apartment block... And Yashka, like all modern kids had his own circle of hip friends and of course a plasma TV....

It was impossible not to fall in love with this cute reindeer who thought he was a dog. And there was definitely no talk from Igor of Yashka Burgers.....

On our first meeting with the idiosyncratic Igor, he drove his truck into town to meet us, bringing with him Yashka and his family of Siberian Huskies. It was really quite comical. There was great fanfare. Men, women and children flocked from their apartments in droves to see them, running alongside Igor's truck as he drove through town, waving and smiling. There was something rather crazily festive about the whole event; the reindeer and Igor's fur trimmed red Canada Goose outfit certainly adding to the somewhat bizarre Christmas-like ambiance (refer "Stranded in Pevek: A Reindeer Called Yashka" http://v2.travelark.org/travel-blog-entry/crowdywendy/9/1532595652.).

Yes, Igor and Tatiana were just a bit eccentric. After all, Igor was not only a tour guide but also a part-time undertaker. Tatiana, on the other hand had a more conventional job as a primary school teacher. But we had thoroughly enjoyed our chance meeting with the interesting couple on our visit in March, enjoying a lovely lunch of shaslik (not reindeer!) and a fun afternoon snow mobiling around their "base camp" property.

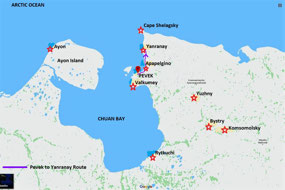

We were keen while we were in Pevek to catch up with Igor, and also contract his services to take us on a couple of day trips to Cape Shelagskiy and Komsomolsky, two destinations within reasonable driving distance and most importantly reachable from Pevek by road in summer. As mentioned many times, there are very few navigable roads in Chukotka because of the permafrost soil and consequent muskegs bogs, and most transport in summer is by sea or air.

Since our March visit Alan and I had been in contact on-line with Igor, with whom we organised our next two one-day trips. Igor could take us to Cape Shelagskiy but because of the lack of roads, it meant something like a 28 kilometer walk one-way from Yanranay. He said he could take us by boat but warned it was very dangerous. The cost was prohibitive anyway so we settled for a day drive to Yanranay and a side excursion to a former gulag site. We were a bit over gulags but there were not too many other places in summer to visit. Anyway we reasoned, the additional trip would give us an opportunity to see a bit more of the northern tundra landscape, about which we were particularly interested.

The following day Igor agreed to take us on a 240 kilometer return trip to the mining town of Komsomolsky.

We knew that the route was by an all year round paved road and had read that the countryside was described in the Petit Fute Chukotka Guide as "breathtakingly beautiful". And it was apparently quite "do-able" in one day. The deal was done. Or so we hoped. Communicating for both parties via Google Translate had its difficulties but one thing we were certain of with Igor, was that he was an honorable man. And we were right.

Re-Uniting With Yashka - My What Big Antlers You Have Grown"!

Dr Alan's prescribed vodka and salt medication had worked exceedingly well and by that morning I was feeling unbelievably good. It was impossible to imagine I had recovered so quickly after being bed bound with my gastric bug for the entire day before. In truth however, I think a lot of my restitution was more probably due to the amount of Lomotil I consumed; as Alan kept reminding me..... But when the dose rate is up to eight tablets per day, it is very easy to go through a heap in a very short space of time.

To make things even better, we were greeted by a perfect Pevek morning. The sun beaming down on a beautiful sparkling Chaun Bay. Not that it was warm but the sunshine was wonderful, adding to my much improved humour.

Igor picked us up in a huge orange six wheel drive truck called a "Vaktofka". As Alex would say in his curious Russian-American accent "Man, this ain't no ordinary truck....". Seating about twenty people, the formidable tank-like beast stood meters off the ground, and was obviously capable of handling any sort of terrain. Like the Beringia Parks 6WD vehicles however, just climbing up the steps and into the cabin was a major feat.

Igor met us at our hotel at 11:00 am and drove us to his apartment site to pick up his friend Vladimir and also his nephew Ivan who was "coming along for the ride". It was also an opportunity to re-unite with our little friend Yashka.

To our surprise Yashka not only had grown substantially in the five months since we had seen him, but he had also grown a huge set of antlers. No longer the cuddly cute baby he was, Yashka was friendly but now in a boofy adolescent manner, his antlers playing havoc with anyone or anything coming close to him.

I must say that Yashka was always a rather comical looking creature; his one black eye giving him a pirate-like appeal and his blunt bovine nose making him look well, just a bit dopey! We always commented that after seeing Yashka our preconceptions of what a reindeer should look like were shattered forever. After all, what about Santa Claus' sweet faced, Bambi-like Rudolph which is portrayed on so many Christmas cards?

Igor explained that Yashka was upset and being difficult because he missed his canine friends. Four days before, Igor had set his three dogs loose into the tundra. It was a practice he undertook every year, presumably to hone up the dogs' hunting skills. Apparently after two days or so, the dogs would make their way home. This time Igor was worried. The dogs should have been home well before now. They had been sighted many kilometers away and although he and Vladimir had been out for hours in their truck searching, they had seen no sign of the dogs.

Our trips over the next two days to Yanranay and Komsomolsky were to turn into dog searching ventures as well. As the days progressed Igor became more and more concerned. We totally understood and of course were more than happy to help out.

TO YANRANAY

Vladimir was our driver for the day. A pleasant and genial man, Vladimir had been part of our visit to Igor and Tatiana's "Base Camp" in March. Very much a Mr Fix It Person, Vladimir had graded a large circuit in the deep snow for us to ride the snow mobiles around and generally helped out with getting all our gear ready and instructing us how to ride what were for us, some very foreign and daunting machines.

I recalled it was only a few days after Alan had accidentally rolled his snow mobile in Magadan, breaking several of his ribs in the process. Not surprisingly we were more than wary of snow mobiles, especially the massive ones belonging to Igor. Rolling one of these would have had us ending up in much worse shape than having a few broken ribs....

Our journey to Yanranay took us back along the airport road, past Igor's "Base Camp" and through the airport settlement of Apapelgino, just 18 kilometers north of Pevek town. Once again, we were witness to yet another deserted village. The derelict ruins of Apapelgino were just as depressing as any other of the abandoned villages we were to see over and over in Chukotka and Far East Russia. And the brutal cement Pevek Airport building at the best could be described as functional; certainly nothing to write home about....

But that's how it is in this extreme part of the world. It is of course easy to criticise. In the short term, it is for the government and the people, almost impossible to solve the problem of cleaning up literally hundreds of abandoned, derelict villages; the cost in the Arctic permafrost environment being almost prohibitive.

Being so far north of the Arctic Circle, the vegetation was already haying off and even the low lie cedars had all but lost their leaves for the coming winter. Unlike the brilliant reds and yellows autumn tones of plants around Anadyr and even the villages along the Bering Strait, the vegetation had turned to deep burnished brown.

It is indeed a strange feeling to travel through the tundra without seeing a single tree, or even a shrub. In fact no vegetation more than twenty centimeters or so in height existed anywhere in the surrounds of Pevek; a town that is famous (or infamous) for not housing one single tree.

Nevertheless, the scenery from the road was spectacular; rich bronze flats flanking the brilliant calm lapis waters of Chaun Bay. The environment however was almost unrecognisble from our winter visit when the countryside was cloaked in a thick white blanket of snow, masking any of the undulations and features of the landscape. But once again the uninterrupted vastness of the uninhabited countryside and indefinable feeling of space was totally addictive. We loved the tundra. It was most definitely our sort of place.

The countryside from Apapelgino to Yanranay was pocked with a myriad of ponds and lakes surrounded by heavy black peaty muskeg. We passed Lake Solyonoye to our left, crossing a number of rivers emptying into Chaun Bay, before finally arriving at Yanranay village. Interestingly these remote rivers were often visited by local villagers and townspeople from Pevek, filling up jerry cans and urns of fresh water for drinking. It is entirely understandable. Reticulated water in this part of the country is virtually undrinkable, mainly due to the state of disrepair of the water pipes. We often commented that the odour from our running shower felt more like we were bathing in sewerage rather than fresh water.

YANRANAY - ONCE A THRIVING REINDEER HERDERS' VILLAGE

Approaching Yanranay

The higher we climbed toward Yanranay, the scanter the vegetation became. Not even low lie cedar could survive here, just tufts of soft cotton weed and lichens. Surprisingly, the black rutile shores of the waveless Chaun Bay were littered with washed up timber. Where would timber come from in such a northern tundra environment? We had heard that like the shores of the Bering Strait, a lot of timber is washed down from great Siberian rivers such as the Lena whose surrounds support rich taiga growth. But it seemed far to long a distance for it to travel, especially given the seas here are frozen for much of the year. We agreed, for us it was yet another Arctic mystery....

And then we saw Yanranay, another deserted settlement with an interesting but tragic history. But unlike the other villages we had visited, there was life in Yanranay. Dotted along the shores of the bay, a number of primitive ramshackle summer huts were inhabited by lone fishermen.

The cottages did however, look pretty well set up, clad with some sort of metallic insulation material and all with heating and some even with satellite dishes. Most had tables and chairs set up outside and all had splendid views of Chaun Bay. The setting, if you could disregard the rubbish, was sublime.....

A man stumbled out of one of the huts to see who we were. After all, there were no vehicles in the village that we could see. On waving to him, he cheerily greeted us, calling out to Alex and asking who were and where we were from. When Alex told him, he shook his head, looking surprised. I guess he would not have too many visitors from Australia. Alex later explained that the huts were only used for the narrow summer season; obviously for the more hardened fishing souls of Pevek.

The Sad History of Yanranay

Yanranay was founded in 1954 during the Soviet days when a number of nomadic Chukchi herder enterprises from Cape Shelagskiy were grouped together to form "kolkhozes" or collective farms. The name of the village is derived from the Chukchi term for "solitary mountain". Yanranay was deemed unviable (see below) and closed by the government in 2015. Like Valkumey the residents were moved some to Pevek, resulting in yet another abandoned village in Far East Russia.

The township which was once home to several hundred people, comprised stores, a school, a theatre, a library, a recreational centre and hall as well as once substantial one and two-storey houses. At one end of town we found what looked like the remains of some kind of food processing (presumably fish) factory. But no-one seemed to have any idea of what was once here. Similarly there is virtually nothing documented on-line nor in any literature we could find, about Yanranay.

One thing we did know was that the reindeer enterprises and subsequently the entire village, was destroyed by the consequences of alcoholism. It was truly shocking. But when you know the story behind the problem, it is entirely understandable. Like our own Australian aborigines, their culture was completely destroyed and their way of life broken forever. And similarly, it was all done for what was probably considered by the government as "the right reasons".

It is impossible to understand what it must have been like for the then nomadic Chukchi herders to completely give up a nomadic life style practised for generations, and to be grouped into collectivised enterprises in an artificial town environment. Their loss of freedom must have been devastating.

During our March visit, Igor had explained at length to us a similar situation which had happened to himself and his family, and also of the difficulties in living in the post-Soviet era.

Originally from Ayon Island, Igor's parents were traditional herders who lived a simple nomadic existence, living in yarangas and following the pastures according to the seasons. During Soviet times, his parents were settled on a collectivised farm and like all nomadic children at the time, Igor was sent to a boarding school hundreds of kilometers away which he attended for most of his school life. He explained that even though the school accommodation was very basic, he was exposed to the relative luxuries of central heating, radio and television. Igor had discovered another life and while it was tough, it was light years away from the hardships of living a herdsmen's life in a yaranga in the Arctic.

After his school days, Igor returned to his parent's home (still a yaranga), a move he and his family found deeply disturbing and very difficult. To exacerbate his unhappiness, he found to his dismay that he was not accepted by his family or the community as a Chukchi, or as a Russian. Fortunately for the enterprising Igor, he was able to take control of his fate. But it was not like that for many of his people....

With stories of collectivisation and child separation such as these, it is entirely understandable that the Yanranay population not only lost its total way of life, but also its culture and self respect. Alcoholism became rampant and reindeer herders were unable to look after their stock. Subsequently, their society ended up in a tragic collapse. What came first - alcoholism or the destruction of their society? It is difficult to determine. Probably, it was the result of both.

Exploring Yanranay

It didn't take long to explore the village of Yanranay. There was very little left. And once again, the village looked like it had been abandoned in one hell of a hurry.

In the meantime, Igor, Vladimir and Ivan took the opportunity to look for the dogs and to ask the fishermen if they had seen them. Sadly, it was to no avail. No-one had seen the dogs, nor had heard of any sightings.

Later, we wandered past the fishers' cottages and down to the beach, just black pebbly gravel along the lonely shores of Chaun Bay.The scenery was in fact rather lovely with the distant tundra clad hills making a very pleasant backdrop to this solitary former settlement. It reminded me very much of what we had seen along the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk in Magadan Oblast during the summer of 2017, and perhaps just a little of our own home village of Crowdy Head on the Mid North coast of New South Wales. The solitude and vast emptiness was breathtaking.

While Alan the others explored the beach area, I walked back up to the township to take some more photos. It was sad to see the remains of a once vibrant village. It was in fact a ghost town now. There was to my delight at least some more life - a curious ground squirrel who looked more than happy with his surrounds. And I also came across some lovely pink cereal grasses and even a lonely Camomile (Pomaluka!). Here is what I saw: https://youtu.be/4DECIhLJt8Y and https://youtu.be/2yvdHBycGTQ

TO THE TRANSIT STATION OF THE GULAG CAMP

More Tundra, More Lakes

Our journey from Yanranay toward the gulag camp took us across the Yanranay River through more tundra, again covered in low lying autumn toned vegetation and dotted with endless lovely azure blue lakes. And more deserted villages.....

About an hour and half into out trip, we came across a working cement factory. A little further down the road was a lonely satellite dish communications base. We wondered where on earth the workers lived. Surely not in the decaying ruins that surrounded both sites? Perhaps they commuted from Pevek? After all, we saw buses taking out many workers every day from Pevek. Again, no-one seemed to know.

Igor asked after the dogs but no-one had seen them.

The Gulag Transit Barracks

Nearly into Pevek town, Igor took a hard turn left up a steeply raised road. In excellent condition, we guessed it was not only a route to the gulag ruins but also a thoroughfare to some pretty serious mining sites. Just to keep a road in that sort of order when it is built on muskeg covered permafrost, and covered with snow and ice for most part of the year would have cost a fortune. A curious sign read along the road "Sanitary Protection Zone", whatever that meant.... Perhaps it was a warning not to dump rubbish?

Sinister as they were, the gulag barracks were situated in a glorious valley surrounded by conical grey mountains and of course more burnished tundra. As we understand, the site was actually a transit station, providing a stopping point and barracks for the wretched prisoners en route to the gulags. The first prisoners would build the barracks, then once completed would move onto their terrible fate at the more distant gold or uranium mines.

I used to wonder why anyone in their right mind would visit infamous European concentration camps like Belsen or Auschwitch. And then I realised we were doing exactly the same. And because of their relative recency, all the camps we visited still contained many of the belongings of the prisoners, left just as they were. And like the abandoned villages, seemingly left in a great hurry.

It was all too chilling. And we had seen too many camps. A very short visit was all we could cope with.

After Igor had another look for his dogs, we were off back to Pevek.

BACK TO PEVEK

Igor took another road back to Pevek, presumably to look out for the dogs. It was incredibly rough and at one stage the bridge in front of us had completely fallen in. But like many other intrepid inhabitants of tough environments that we had met on our travels, nothing fazed Vladimir and Igor. We just forged through the river by the side of the fallen bridge! Here is a video of our trek: https://youtu.be/Zq1VSs9HQkg

We arrived back in Pevek at 6:30 pm. It had been long day and for some reason we had not eaten. We always complain that we don't need much food. We laughed. So perhaps we had been taken more seriously than usual?

Alex was ravenous and decided to have an early dinner while we left him to do some grocery shopping. Eating at that time of the day just does not suit us, even if we are hungry. Anyway we needed to stock up on groceries and of course, some beer and wine.

In the grocery shop, we were surprised to hear an American voice, and a Russian accented voice speaking English. Of course we couldn't help but introduce ourselves. As it happened Ben and his colleague Evgeny were scientists who worked on Wrangel Island, monitoring polar bear populations. "How do you tag a polar bear?" we asked. It was obviously with a degree of difficulty and of course a high level of danger.

Ben and Evgeny were in Pevek waiting for a helicopter flight to Wrangel Island, but weather conditions had not been favourable. We promised to meet up for dinner one evening. And as it happened we did run into them several times but unfortunately events overtook our opportunity to dine with them. A shame. They were good company and it would have been great fun.

Alex came with us to dinner. While he wasn't eating, he decided we needed looking after and he was most probably right! We dined again at the Ramushka, ordering a meal of Halibut in a very rich creamy sauce - which was probably very unwise given my recent stomach situation.

We are definitely not wusses when it comes to drinking but we were often surprised at the level of hard liquor intake in Russia. Just as we were finishing our meal, three very inebriated men walked or rather staggered into the restaurant. One was completely paralytic. According to Alex, they were interested in sourcing local walrus ivory. How he could tell was beyond us as these guys could barely speak. To our astonishment, they ordered three bottles of vodka and three plates of fried eggs. And then they insisted Vera the waitress - who looked like she could kill them - turn up the music full blast.

Alan looked at me, turning a funny green colour. "Let's go!" he gasped. Poor Alan, like me had come down with the same awful gastric attack. I totally sympathised. It was a long night....

POSTSCRIPT

We were deeply saddened to hear of Yashka's death in 2019, after he was accidentally hit by a military truck. Igor and Tatiana were devastated, as would all of Yashka's friends and followers. We do not know of any details.

Pevek, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russian Federation

Pevek, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russian Federation

James

2020-05-24

Amazing adventure! I've been checking out all these tiny seemingly abandoned towns on Google earth and trying to find out information about them so was really happy to come across your journal, thank you for sharing. Do you know if he ever found the dogs?