A LONG AND VIOLENT NIGHT.....

It was a long and arduous night for Alan who had succumbed to my awful gastric bug. Given the two day incubation period, it was obvious that it was not simply a case of food poisoning but more likely a type of rotavirus, a highly contagious virus well known for its sudden onset of fever and violent gastric symptoms. And over the next few days, a lot of the other hotel guests had come down with the same bug. It was awful. You could actually hear the sounds through the room walls of the unfortunate people wretching.

Lurching from a constant alternation of vomiting and diaorrhea, Alan had barely slept at all. I readily admit that I am not a very sympathetic nurse. But I sure did feel sorry for him that night. And just a bit guilty as to the sizeable hole I had made in our anti-diarrhoea medication Lomotil.....

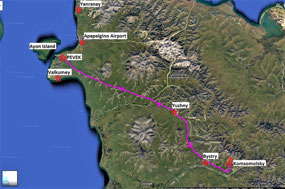

We were scheduled to visit Komsomolsky that day, a return journey of some 240 kilometers. As there was obviously no way Alan could make the trip, I suggested we put it off until the next day. But he was adamant we should go without him. All he wanted was to be left in peace - in bed. I understood totally. And as it happened, it was just as well. It was to be a very, very long day....

JOURNEY TO KOMSOMOLSKY

On Our Way

And so Alex and I took the trip to Komsomolsky with Igor, Vladimir, Igor's cousin Nastia and her grandson Ilya, a child of about five years of age. "It will be good for Ilya to learn about the tundra" explained Igor. I was not so sure.... It would be hard on a five year old travelling in our Vakhofka all day. But I guess he was another pair of eyes for which to search for Igor's dogs who had still not shown up.

And by now, Igor was becoming more than concerned.There had been sightings of two dogs along the Komsomolsky road. But that was days ago and there had been no sign of them since; nor any sightings of a third dog. Being a hopeless animal tragic, I fully understood how frantic he must have felt.

Although we arrived early for some reason we didn't leave Igor's base until 11:30 am, much later than I would have anticipated for such a long journey on what I gathered was a pretty rough road in places. But a very distracted Igor was on his phone full time and I expect he was organising our trip to maximise his chances of sighting the dogs.

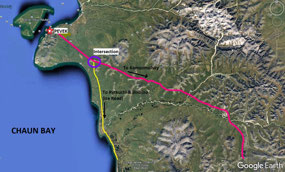

On the outskirts of Pevek we passed huge storage containers of fuel, endless rows of refrigerated containers and literally hundreds of huge semi trailers - obviously all there to provide for the local and outlying population for Pevek's long freezing winters. It is easy to forget that you are so far from food and fuel supplies in remote, remote Pevek. Such sights were sobering reminders of the bitter reality of keeping a population warm, fed and alive in this distant Arctic outpost.

There are very few roads in Pevek but the Komsomolsky road was for the first part, in very good condition. At the first major intersection Igor stopped to look for the dogs while Alex and I wandered around looking at the road signage. The road forked in two directions: straight ahead was the route to Mayskiy and Bilibino and to the right was the winter ice road (zimnik) to Rytkuchi, Bilibino and Kupol, home to the huge Kinross Mining site. This zimnik was the very road we had travelled on our trip by Trekol from Bilibino to Pevek in March 2018. It was indeed a strange feeling to be seeing it not only in broad daylight (we had passed through here at about 3:00 am on a dark, formidable and blizzarding night) but with no snow and ice.

Surprisingly, the signage read: 624 kilometers to Bilibino on the Komsomolsky road yet only 338 kilometers on the zimnik. It is easy to forget that much of the zimnik passes straight over frozen rivers and sea in winter, shaving off almost half the distance of the route from Pevek to Bilibino. Yes, it is totally counter intuitive for us being much easier to travel in Chukotka by road in winter than in summer....

For the next seventy kilometers or so, we travelled though gently sloping, golden tundra clad valleys. Once rich reindeer pastures, the land had apparently been significantly degraded over the last 80 years by constant mining. And from what I gathered from Igor there are virtually no viable reindeer herds now. Left was just a semi barren environment housing patchy low vegetative growth with poorly drained soils and thick muskeg. The only signs of life were the continual rows of fallen power poles and lines, testament to the continual movement of the deep permafrost soils. Precariously tilted at terrible angles or lying hopelessly like fallen soldiers across the tundra, I wondered how on earth they transmitted any energy at all. And what would happen in winter when they would almost certainly be covered by meters of thick snow? Again, no-one seemed to know....

Igor was a true idealist. He talked with great enthusiasm about his dream of establishing a reindeer industry not far from his base at Pevek. Here, he explained he could provide not only fresh meat for the community but also good employment for the locals. He was after all, the product of generations of reindeer herders and should know what he was talking about. Communicating through Alex as interpreter, I asked if Igor was serious. Alex was adamant that he was and it should be entirely possible through government seeding grants to fund at least the start of a herd. I thought about Yashka and knew he would not be at all keen....

Igor also talked in length about his dreams to create a tourist centre. This remote tundra environment and surrounding mountains would be he thought ideal for hiking. In winter, as we had found, it would be good for snow mobiling and perhaps cross country skiing. There was no doubt about our Igor. He was such an enthusiast you couldn't help but be caught up in his excitement about his prospective ventures. I couldn't help however but think about bears and wolves in summer and about a situation fraught with impossibilities of bringing in food and supplies in winter. But I had to admire him. Igor had all the answers and nothing could suppress his indefatigable enthusiasm... And I did notice a rather large gun lying casually across the floor of our Vakhoffka....

I love the names of some of the remote Russian co-ordinates and villages. It is almost as if the country is so vast the people have simply run out of ideas for names. I adored the name of the location of The 19th Corner, for which my last blog was named. And I loved the name of the 47th Kilometer - yes exactly at the 47th kilometer along the Komsomolsky Road. They were after all, names with some sort of significance. Igor said we could stop to fish for Grayling (a type of freshwater salmon) at the 47th Kilometer but for some reason, it didn't quite happen... And it was probably just as well. This was to be one hell of a long trip.

The further we travelled the rougher the road became, bouncing us unmercifully around in our hard seated Vakhoffka. At some points there was only room for one vehicle. When I commented that there seemed to be a lot of politeness about who was allowed to pass first, Igor explained that all vehicles driving to Pevek have the right of way. It made a lot of sense.

We stopped for a while at what looked like a deserted outpost, apparently once a power conduit and stopping point along the Komsomolsky road.

Igor explained that it was once a place where they executed prisoners in the days of the gulags. The story was vague but bleak. And the interior of the building was forbidding enough to imagine what had happened there. We had seen enough of the former gulags and I didn't really want to hang about, particularly as we were still a long way from Komsomsol. But it was a chance for Vladimir to stop and for everyone to look out for the dogs. Sadly, there was no sign of them.

Soon after we crossed the Pryrkayvaam River where a semi trailer was parked and the driver was syphoning fresh water. Igor and Vladimir talked to him for some time but he had not sighted any dogs on his travels. Not far after, we stopped another truck whose driver gave us the same answer.

Not far from Yuzhno, we passed a series of kekurs or rock stacks, just sitting up alone in the nakedness of the tundra. Formed by eroding wind forces, these cores of hard rock are typical formations of Chukotka and in the vast barrenness of the area, like mini volcanoes are visible for many kilometers.

First Stop - Yuzhny Village

About 70 kilometers out of Pevek we came to the village of Yuzhny. Actually, it would be easy to drive past Yuzhny village without even noticing it. Another deserted village, it was just a muddle of collapsing houses and of course more wreckage and rubbish.

Although Yuzhny was no longer inhabited, the mining company "Chukotka" still worked the area. I suspected it was one of the sites we saw miners ferried to from Pevek each morning.

While Igor and the others took the opportunity to look for the dogs and collect shushka berries and mushrooms, I wandered the lonely streets of Yuzhny and here is what I saw: https://youtu.be/vFyFAkC3rtg (apologies about the sound - it was blowing a gale).

Yuzhny was the first of the gold mining towns to be opened in Chukotka. Established in 1950 by a group of geologists, it began its industry by employing normal prospectors. Sadly, it soon became part of the Chaun Chukotlag, the local division of the Dalstoy gulag system.

By 1999, most of the gold reserves were depleted and the mines were deemed unviable. The town like so many others was closed the same year, with the Russian government funding the transport and settlement of pensioners and unemployed to other parts of Russia.

There is nothing I could readily find on-line about the fate of the former miners. It was of course post-Soviet times and an economic climate of great poverty for Russia in general.

I walked the empty streets of Yuzhno deep in thought about the former miners and their families, the shop owners, the school teachers and the administrators; wondering what their lives were like in the busy mining era and whether many were still alive. Abandoned villages such as these certainly leave a haunting imprint. And I was not sure I wanted to see any more...

We spent a long time in Yuzhno looking out for the dogs. In the mid afternoon, I wondered about the sense of travelling on another 70 kilometers or so to Komsomolsky. It would most likely be the same sort of abandoned sad township. But I reminded myself that it was of course the journey not the destination. And anyway, I had no choice. I was totally out of control and in the hands of Igor. And we did need to find those blessed dogs....

Through Bystry to Komsomolsky

The further we travelled toward Komsomolsky, the more barren the countryside became. Foliage on any of the plants and grasses had totally died or hayed off in preparation for the cruel winter freeze. In the late afternoon light, the tundra no longer looked beautiful - but harsh and uninviting in the heavily mining degraded savage countryside. At least the unimpeded countryside allowed us to have a good look for the dogs.

During our long journey to Komsomolsky I was deep in conversation with Igor and somehow missed even noticing Bystry, a mining village which apparently closed between 2003 and 2004 when it ran out of gold. Like Yuzhno it bore the dubious status of being yet another abandoned settlement in the middle of frigg'n nowhere.

I had an interesting but slightly off beam conversation with Igor. What did we do now we were retired? I talked about our large gardens and the beaches where we could walk and swim. Igor was more than interested. "What do you do that takes all your time with your gardens?" he asked. I guess that was a very fair question from someone who would never be likely to have a garden in Arctic Pevek. We do have very large gardens at home and when I explained about the time it took to just mow our lawns, Igor was incredulous. "What? Two days just to mow your lawns? How often do you have to mow them?" And when I said that in summer it was probably every two weeks, he was dumfounded. "I can't believe that!" he exploded. "You must send a me a photo of this grass". I promised I would.

I recalled I had a similar conversation with Bold, our guide in Mongolia who asked me why anyone would bother wasting time gardening. "We can't waste time bothering about gardens. We are too busy surviving" said Bold. His comment threw me but like Igor, it sure gave me food for thought. And in the middle of the desolate Russian tundra, mowing lawns and gardening did sound totally absurd....

Igor was also interested in our route from Australia to Russia and asked why we travelled via China. It must have been solely for convenience he said. After all, no-one in their right mind would want to visit China, would they? When I explained that we had travelled widely through China and actually loved the country, he was even more confounded. "I hear the Chinese are lazy people and the country is badly run" he said. When I told him nothing could be further from the truth he was totally surprised. Igor was not being racist. Rather, he was simply curious and totally intrigued about our experiences in China. Our conversation was somewhat bizarre but it was fun and certainly filled in the bumpy and uncomfortable hours before we eventually reached Komsomolsky town....

KOMSOMOLSKY

A Bleak Welcome

We arrived in Kosomolsky during the fading afternoon at around 5:00 pm, our trip having taken a very long four and half hours. It was certainly time to stop for a breather and perhaps even have something to eat. But as we were to find it was no place in which you would want to hang about for too long....

A horrible scar in an otherwise splendidly beautiful location, Komsomolsky was about a depressing and ugly township you could ever imagine. We had read as much as we could about Komsomolsky, a town originally developed by volunteers of the Russian Soviet Youth Movement (Komsomol) and were looking forward to our visit. Bitterly disappointed, I looked around for at least something that was pleasant to photograph but in truth I could find nothing at all pleasing - or even remotely interesting, other than a drab decaying township that for most part looked as abandoned as the other settlements we had witnessed.

About Komsomolsky....

Komsomolsky was founded in 1959 by young Komsomol members who had volunteered to travel to Chukotka to establish a mining industry. And indeed it was the "Komsomolets" who were the first settlers of the township. Soon however, it became the domain of gulag prisoners and deportees who unlike the Komsomol volunteers, had no way of leaving. And within a short period of time, Komsomolsky became one of the largest mining sites in the country. Barely thirty years later however, the mine was deemed no longer economically viable and by 1998 the settlement was mostly depopulated.

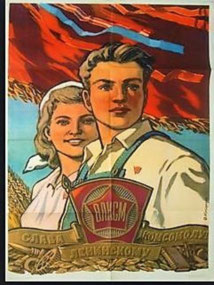

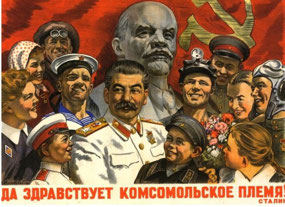

The Komsomol

The Komsomol movement was established by the Lenin Soviet government in 1918 as a youth division of the Communist Party. Formally it was established as an independent body catering for young people aged between 14 to 28 years of age, but in reality it was primarily a political organ for spreading Communist teachings and preparing future members of the Communist Party. Closely associated with this organisation were the Pioneers - or All Union Lenin Pioneer Organisation which catered for ages 9 to 14 years and The Little Octobrists for the very young. All youth bases were well covered.

Interestingly, the Komsomol had apparently little influence on the policies of the Communist Party or on the government of the Soviet Union, but it did play a key role in shaping Communist values of young people. The organisation acted as a mobile pool of labour and political activism, with the ability to locate resources to high priority areas at short notice. Being a Komsomolet was considered important in gaining membership and eventual leadership in the Communist Party. And not surprisingly, active members received privileges and preferences in promotion; the benefits of keen membership being obviously very worthwhile. In the 1970's and early 1980's, membership peaked at a staggering 40 million.

Following the reforms of Mikhail Gorbechev's perestroika and glasnost, Komsomol poor management and dubious practices were exposed, and the organisation began to lose impetus. In September 1991, the organisation was formally disbanded.

A Long Hour in Komsomolsky

Two mines still operated in Komsomosky: the Chukotka Industrial Co-operative and Quasar Mines.

Igor parked outside of one of the mining complexes, telling us to stay inside the Vakhoffka while he went into a small office at the front gate presumably to see the management. The staff all seemed to know Igor and like everyone we met that day, greeted him in a warm and friendly manner. After about ten minutes he re-appeared, telling us we could get out but to stay close to the Vakhoffka and not to walk around the mining site - while he attended to some business - and probably asking after the dogs.

While Nastia and Ilya slept in the van, Alex and I carefully walked a few meters into the base site. Within a minute or so, there was a loud shouting. An angry armed guard was barking orders at us, presumably not to enter any further. Golly, now this was friendly.... I also wondered what the hell we were doing there. There was certainly nothing to see.

Eventually Igor appeared with Vladimir, Nastia and Ilya. They asked if we would mind if they performed a Chukchi ceremony up at the local cemetery. It was obviously important to them and they promised they wouldn't be long. Alex and I would have liked to accompany them but we were not invited, so we hung around the miserable entrance to the mine pretending to look interested in the vegetation. God, there was nothing else.... And even that was pretty uninteresting. We thought about visiting a shop to buy some food but apparently there were no shops now in town. There were also no toilets we could see, so we just waited and waited.

I looked at the morose surrounds, the decaying buildings and the tragic sadness of a dying town. I wondered what the Komsomolets would have thought. I imagined their enthusiasm when they first arrived as young and energetic idealists building the future for Chukotka and The Mother Country. I envisaged them working hard in their bright red, white and blue crisp uniforms; their youthful faces bright and full of cheer. I tried to imagine their excited voices singing as they marched. But I heard nothing. Komsomolsky was already a moribund town.

On top of the hill above the town we could just make out our party at what was presumably the local cemetery. Half an hour later we were still waiting.... We were both getting tetchy about our long return trip home and the fact we hadn't eaten all day. Even if we had left there and then we knew we would not be back in Pevek until very late in the evening. And there was no point in trying to call Alan as we had no phone reception. A good thing Alan never gets worried, I thought....

I was becoming rather culturally intolerant by the time our party returned, especially when it was suggested that if we waited just twenty more minutes we could buy some food from the mine canteen. But there was of course no point in refusing. Everyone needed some food, especially Vladimir who had been driving all day.

I wish I had been able to take a photo of the mine canteen. But I would not have dared. Obviously I was very foreign looking as the miners and staff just stared at me unbelievingly. And I couldn't blame them. I had to smile to myself, thinking "Yeah, I guess they don't see too many Australian tourists in Komsomolsky!"

The food was all hot stews, heavy looking pies, cabbage and potatoes. Given the still fragile state of my stomach I decided to give the food a miss. I noted Alex did too. Thankfully Igor found some sweet buns of which he bought a huge bag. Dry, sweet and tasteless, they were however a real god send.

BACK TO PEVEK

On sunset we finally left Komsomolsky for Pevek, a long journey again punctuated by numerous stops to see if we could see any signs of the dogs. Igor tried to put on a brave face but Alex and I could feel his growing despair and felt very sorry for him.

He rang Tatiana who said she had heard nothing of the dogs either. But amazingly, she had heard from Alan who was worried about where we were and had asked the Pevek Hotel staff to call her for him.

The surroundings on our journey "home" however was not without a certain beauty. In a startling sunset even Yuzhno looked splendid; the enormous sky reflecting deep pinks and mauves and the sun gradually disappeared into the black pencil sharpness of the horizon.

The sun seems to take an inordinate amount of time to set in these high lattitudes. Just as we came close to Pevek, the sun finally set. But even then, Igor insisted on getting out of the Vakhoffka for one final look for the dogs; but sadly to no avail.

We arrived back at Pevek at 11:00 pm. Thankfully, Alan was looking a lot better. He explained that he had used our iPad via Google Translate to explain to staff member Angelika about his concern for us. Miraculously the translator worked (it is often tricky) and the lovely Angelika rang Tatiana who confirmed we were fine.

Unlike Alan who was still nauseous, Alex and I were ravenous. By some miracle we managed to find a supermarket which was still open and bought - yes, you guessed it - a loaf of stale bread, cheese and salami....

Pevek, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russian Federation

Pevek, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russian Federation

2025-05-22