ON THE FIRST PART OF THE JOURNEY.....

Meeting Yura

Yura was looking worried. And he had every reason to be. He had just arrived in Yakutsk after having undertaken a challenging 1,000 km overnight winter drive from his home township of Oymyakon - the coldest settlement on earth - to pick up two Australian tourists with whom he would spend the next five days driving back to, and around the Oymyakonskiy Ulus (district). Furthermore, not only were they foreigners but they were old and to his knowledge, spoke absolutely no Russian.

With very limited English language and no accompanying English-Russian speaking guide, even the most experienced Russian tour driver would find the next few days quite daunting. Given the potentially lethal Arctic winter conditions in Oymyakonskiy, looking after these foreigners was a considerable responsibility.

And there was no time to rest for Yura. Not even a meal and a quick nap. We were departing first thing for our first destination of Khandyga, some 450 km east of Yakutsk. Driving is a tough - and dangerous - business in Arctic Russia.

Sitting uncomfortably in the foyer of our Tygyn Darkhan Hotel, Yura carefully scrutinised passing hotel guests, no doubt concerned about his new most-likely-to-be-tiresome-tourists. He was easy to identify. "Извините меyя. Меyя зовут Венди Моррисон. Ты наш водитель?" (Excuse me. My name is Wendy Morrison. Are you our driver?) I asked nervously in my halting Russian. Yura looked up, smiled warmly and nodded. I think we were both relieved. He looked friendly and very much our sort of person. But perhaps Yura mistakenly thought I may speak some Russian? And he probably would not have seen I could hardly breathe let alone walk. It was however, a good start. But where was Alan?

A Stiff and Sore Start

Despite a relaxed previous day in Yakutsk, Alan and I woke up stiff and sore, and would you believe just a little bit tetchy? Alan's battering and bruising from his excruciating 20 km snowmobile sled ride to Saskylakh two days before had finally taken its toll.

He was black and blue, and could barely walk. And somehow, I had managed to damage the cartilage around my ribs - no doubt due to the exertions of Extreme Undressing and Dressing into Thermals in Ilya's tightly packed Toyota Prada. Coming to think of it, I did recall a nasty burning sensation around my ribs when I tried to yank off my uncooperative one-kilo snow boots.... And after all, in the haste of the situation I did manage to lose my trekking trousers.... That morning, every movement and every breath was murder.

Yes, it was all quite explicable. But it didn't help our humour trying to pack for our coming trip to the Pole of Cold, a journey at that point in time about which neither of us was particularly excited.

Ed had explained right from the beginning that our Oymyakon tour would be just us and a non-English speaking driver. Disturbingly, he also mentioned that there was "not much to see or do on the Oymyakon trip", so there was little need for a guide. He also mentioned that during our journey, we would be buying meals from roadside cafes, taking pains to explain that we would just have to get by with my almost non-existent Russian supplemented by Google Translate. And when things really got tough, just pointing.

Other travel information I guessed would include times that we would leave for our travels, names of the villages we were in and what was necessary clothing for each day. Oh, and of course how to ask for a toilet stops and where to buy drinks and snack foods.... I made sure with my Russian friend and teacher Olga that I could ask such questions in a somewhat understandable manner. Olga thought it was all very amusing. Neither of us was particularly hopeful about my success, I must admit. And god only knew what we would do if one of us got sick....

Furthermore, Ed had warned us well in advance "Your travels to and around Oymyakon are likely to be much colder than what you experienced on your Anabarskiy tour. Whenever you go outside, wear everything you have". Colder than what we had experienced in Anabar? Well yes. In February the average temperature range in Oymyakon is an unbelievable minus 47 C to minus 35 C! We knew that putting our warmest clothing on was quite some considerable effort and inconvenience. But I just wished we had taken more notice of his warning....

Our Tour to Oymyakon

We must have looked decrepit, staggering painfully with our luggage and heavy overcoats. And once again we were reminded of the lack of ramps and the treachery of icy Russian hotel stairs in winter. Even though the Tygyn Darkhan had provided a carpet across their stairs, it was covered in semi-frozen snow and slippery as.... Having skated down to the carpark, we soon were packed tightly into Yura's Toyota Ipsum sedan and speeding off on a frozen morning through the snowy streets of Yakutsk east toward the Lena River ice road.

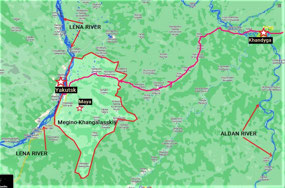

Our journey that day would take us some 450 km along the Kolyma Highway - aka Road of Bones - through the four ulusy (regional administrative divisions) of Megino-Khangalasskiy, Churapchinskiy, Tattinskiy and Tomponskiy to the small township of Khandyga where we would stay the night in a private hotel. The following day we would head off on a further 500 km trip to our destination of Oymyakon, and what was apparently a series of small villages in the ulus of Oymyakonskiy.

You may well ask why we made this long journey a return road trip. In the beginning it sounded quite simple. Initially we had wanted to drive the first leg of the journey to Oymyakon, then fly back from to Yakutsk from Ust Nera which on the map is not that far from the villages of Oymyakonskiy.

But as Ed explained, we would have to pay for the return of the vehicle and driver, so it would be more economical to travel back in the car. What we didn't realise either, was the although Ust Nera looked close on the map it is actually some 440 km from Oymyakon, and takes some seven to eight hours to drive. Or that our driver actually lived in Oymyakon....

And so, we resigned ourselves to a 2,000 km return road trip. We had the time to spare and anyway, we were pleased to be "re-connecting" with the Road of Bones and driving back would be just another experience of this vast and grimly historical region. As mentioned, we would be travelling from west to east, another 1,000 km of the road which we had already travelled on in 2017, north-east from Magadan some 350 km east to west to Talaya. The two trips combined would account for almost 70 % of the total length of the notorious gulag route. Again, it was the old adage of "the journey not the destination".

Note: Some time after our tour, Yura formally changed his given Russian name or "емя" to that of Ilgen - a name derived from his Yakut ancestors. For this blog however, I will refer to him as Yura, as he was known to us then.

Back with Lena - Along the Ice Road to Nizhny Bestakh

For this journey, I had the advantage of sitting in the front passenger seat next to Yura where I could hopefully take the best photos possible for our blog. Alan obligingly sat in the back, able to more comfortably stretch his long legs. Yura turned on some hauntingly beautiful Yakut khumus music; a pleasingly relaxed start to our travels.

At the time, I recall thinking that Yura's Toyota Ipsum sedan looked smallish for a tour car faced with such extreme climate conditions. But of course, it was a four-wheel drive.... And I consoled myself that it looked light enough to be readily pulled out of a snow drift bog. God forbid, if we were so unlucky again....

You easily forget just how short the day length is in these high latitudes. Speeding over the frozen Lena River zimnik around 9:30 am it was surprising that we were still travelling in the eerie light of an early dawn; the sun as we had so often observed, just a pale glow in a featureless, amorphous silver sky.

Here at Yakutsk, the complex braided Lena River spans a massive area of some three to five kilometers in width. The coldest major urban centre in the world, Yakutsk is also the largest urban area that cannot be reached by an all-year road. And there is just one winter road to and from the city. At present, there is no bridge over the Lena anywhere in the Sakha Republic. In winter, the frozen Lena provides a vital road route. In summer it provides a route for ferries and boats. In spring and autumn there are times when there is no river access because of the movement of melted snow or semi-frozen ice. During these times, travel by helicopter or hovercraft across the river are the only options.

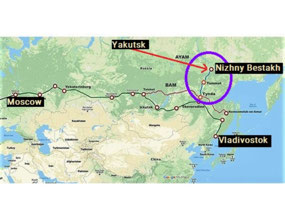

Rail transport is accessible from the neighbouring settlement of Nizhny Bestyakh, some 23 km east across the Lena River. Plans are apparently now well in place to build a bridge over the Lena to ensure uninterrupted year-round road and rail transport for Yakutsk.

We had followed the Lena River south-west on the first leg of our Anabarskiy journey. On this occasion we were travelling east toward the beginning of the notorious Kolyma Highway which technically begins at the settlement of Nizhny Bestyakh. On a morning of minus 28 C, I felt strangely warm; perhaps with the knowledge and comfort of being back in the familiar arms of the Lena - the longest river in Sakha Republic (4,294 km) and one of three great rivers (along with the Ob and the Yenisey) of Siberia.

Nizhny Bestyakh

The township of Nizhny Bestyakh is located just across the river from Yakutsk. A busy centre, the settlement's snow-clad main street boasts rows of shops, modern shopping complexes and a surprising amount of traffic.

Nizhny Bestyakh is now a significant transport hub for the city of Yakutsk and the Sakha Republic and is one of the developing localities in the Far East. Located in the Megino-Khangalasskiy Ulus, the settlement is the meeting point for the two major Federal Highways of the A360 Lena to the west and the Kolyma to the east. And it is also the junction for the southern Amga Highway to the settlement of Tynda.

Nizhny Bestyakh is also the terminus for the Amur-Yakutsk (AYAM) Railway Line which runs south, intersecting with the Baikal-Amur Mainline (BAM) line near Tynda. From here it is possible to travel by rail via the BAM or further south, the Trans-Siberian Railway to Moscow in the west and to Vladivostok in the east. Interestingly, although the railway from Tynda was built some years before, for a long time it only took passengers to Tommot, about half way between Tynda and Yakutsk. It was only in 2019 that it began taking passengers all the way to Nizhny Bestyakh.

Yura pulled our car into a supermarket car park in the village, explaining that he needed to eat and that we might do some shopping for anything we may need on our coming journey. We were relieved. Yura's English was far better than my Russian and from the beginning of our trip somehow, we managed to communicate surprisingly well. And a supermarket visit was always a most welcome stop of us. Yura however, would not hear of having a break after his long drives. A soon as he had eaten, we were off on our travels east.

Megino-Khangalsskiy Ulus at a Glance

We were travelling along the Kolyma Highway through the Megino-Khangalasskiy Ulus, one of the 34 municipal regions in the Sakha Republic. A relatively small region of just 11,700 square kilometers, Megino-Khangalasskiy is bordered by the Ust-Aldanskiy District to the north, Churapchinskiy District to the east, the Amginskiy District to the south-east and the Khangalasskiy District (where we had journeyed on the Anabarskiy travels) to the south-west.

It is bordered of course, by the Lena River in the west. The population of the ulus is around 30,000, with around 23% located in the administrative centre of Mayya. The population is predominantly Yakut, accounting for some 91% of inhabitants. Russians are the next largest group of around 6%, with minority populations of Evenks and Ukrainians.

Like Yakutsk, the region experiences massive temperature differentials. The average winter lows are around minus 50 to minus 40 C. In summer the average highs range from plus 25 C to plus 30 C.

Interestingly, the tiny ulus is one of the most significant agricultural districts of the Sakha Republic. It specialises in meat and dairy production, as well as intensive horticulture. The ulus is well known for its progressive farming programs and well-regarded agricultural education.

Villages Along the Kolyma. A Word About Yura

Our drive for the next 100 km along the Kolyma Highway passed through mostly flat countryside dotted with areas of familiar taiga vegetation and interspersed with cattle and horse breeding farms. Along our way we passed through a number of small villages including Tyunyulyu and Nuorogana. Behind Tyunyulyu was a large lake of the same name. But in the winter season it was - well, frozen and certainly not visible on our travels.

Yura tried as hard as he could to articulate the village names and he obviously did a great job as from my voice recorder I had them recorded fairly accurately.

We were during our coming travels to have great fun trying to converse with each other; Yura wanting to learn more English and me desperate to understand and have the opportunity to speak more Russian. As I had found, learning a language from books and audio at home on my own is not an easy nor an efficient process.

A young Yakut man, Yura was pleasant, easy going and good company. And an excellent driver. To our amusement - and relief - his favourite English saying was "No problems".

As we drove along the Kolyma, he told us a little about his life at Oymyakon. His mother was a local school teacher and his father was also a driver who mostly worked for local mining companies. Yura did a lot of driving for tourist companies. He was, he told us, very keen to start up his own business. He just needed more English language, he affirmed. With most of his work centred in Yakutsk, was he living mostly in Oymyakon or Yakutsk, we asked? "Oh, I'm just a nomad" he would laugh....

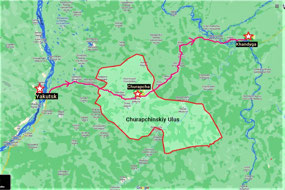

Through Churapchinskiy Ulus

For the next hour or so, our drive along the Kolyma took us through the flat environs of the Churapchinskiy Ulus. In the distance we could see small villages and farms, brightly painted roofs dotting the mostly taiga landscape.

A region of similar size to Megino-Khangalasskiy, Churapchinskiy's main economy is also mainly based on agricultural industries, including horse and cattle farming, and horticulture.

The population of around 20,000 inhabitants is mainly comprised of Yakut people (97%) with Russians, Evens and Evenks accounting for the remainder. Churapcha is the administrative centre. The region is well known for its abundant lakes - once again invisibly frozen.

Interestingly, summer months in Churapchinskiy are considerably colder than those of neighbouring Megino-Khangalasskiy with July averages of plus 16 to 17 C.

ON THE SECOND PART OF OUR JOURNEY

Tattinskiy Ulus and Introduction to the "Real Cold"!

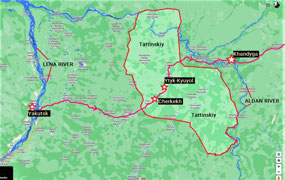

We had just past a road sign "Magadan 1,838 km" when we entered the Tattinskiy Ulus. The Kolyma Highway so far had been an excellent, well maintained sealed road. A faint feeling of sadness overtook me, and fleetingly I wondered just how bad the road would have been if we had managed to travel all the way to Magadan. I expect I will always yearn to complete the journey....

But there was no time for second thoughts. Just before Cherkekh, Yura pulled off onto a track leading to a roadside cafe. "Well, this will test my Russian language" I thought lamely. We had grown to appreciate the small roadside cafes on our journey to Anabar. They were always spotlessly clean and the food, although plain and usually a bit heavy, was simple good cold weather eating fare. There was always borsch, good salads, the ubiquitous piroshki, pelmeni and groan - of course more dry bread. And I need not have worried about my language. Yura as always, offered to assist us but it was easy even for me, to identify the food and order a meal.

Visit to the Cherkekh Historical and Ethnographic Museum OR How we Nearly Died of Cold....

I might have been worried about my lack of Russian language at the cafe, but I should have been really worried about our lack of understanding when we arrived at the Cherkekh Ethnographic Museum. It didn't help us either that neither of us are ever keen to visit museums* and we had only reluctantly agreed to "just a few" if Ed had thought they were worthwhile. In fairness, our experience at the museum was somewhat our own fault. We had not done our homework and we were soon to pay the price....

*It may sound we are like heathens but our dislike for orchestrated tourist activities and endless unnecessary museums is well documented in all of our other blogs

Yura explained as best he could that he would drop us off at the museum and return in about an hour. He was apparently visiting a friend in Cherkekh who had recently experienced a very bad car accident and was now wheelchair bound. We understood. We also understood that few guides, let alone drivers, ever accompany their tourists into museums. After all, they had seen it all before. Many times....

Thinking it was an indoor exhibition like most museums, we only wore our lighter outside gear. Just before we entered the museum building however, I suddenly recalled what Ed had told us about wearing "everything we had" when we left the car. We grabbed our down overcoats from the car; both cursing that it was ridiculous overkill.

Yura accompanied us to what we thought was the museum building but before he left, he gestured to the outside saying something like "walk the territory". He left and once paid, the woman in charge who spoke no English, firmly showed us the way out of the building. And closed the door.

To our dismay, we realised that it was indeed an outside museum. In the distance were what appeared to be two church buildings and a number of other old dwellings, including a yurt. The administration building door now firmly closed, we had no option other than to "walk the territory".

On a beautiful clear sunny day, it is hard to explain just how cold it was. We were only wearing super light trekking trousers and of course, we hadn't taken our mittens or even gloves with us. Nor did we have any hats or scarves. The walk became a trudge through super thick snow; a track barely wide enough for two human feet. Stumbling through the snow and falling into ice drifts was certainly not our idea of a fun afternoon. And to make matters worse, we had no idea whatsoever what the museum was meant to portray. Not only was there no English signage, there was virtually no signage at all.

There was no doubt however, that the churches were absolutely stunning. Gracious statuesque old wooden buildings surrounded with thick meringue snow, they stood regally against a brilliant azure sky. Next to each building huddled a cluster of snow-covered fir trees. If the cold hadn't taken our breathe away, the churches certainly did.

We ventured inside the larger church. Beautiful murals adorned the walls illuminated as so often we had seen in old churches, by piercing rays of golden sunlight. But it was cold and as we had no idea of the significance of the church, our stay was just long enough to take some photos before we headed to a second much older looking chapel.

If we had thought the first church was cold, we were in for something else. The little chapel felt like walking into a refrigerator. We only spent a very short time in the primitive building before we realised that the cold was no joke. At a guess, the temperature must have been around minus 45 C. Perhaps colder.

This was serious and just how inexperienced people get themselves into trouble. Hands and feet aching with the cold, and shivering violently, we left for the safety of the administrative building. Alan was feeling lightheaded and dizzy, I was feeling nauseous and just plain sick. It was a truly horrible experience. But at least it was only Stage 1 of hypothermia, I consoled myself. Apparently, the dangerous part starts when you stop shivering and become confused. We weren't disoriented. Just cold and pissed off!

On our way back we did stop at the yurt but again, it was just a fleeting visit. It was hard to believe, but to my horror I began to experienced violent stomach cramps. And I only just made it back to the main building.... Our long trudge felt like years. Thank goodness the woman in charge was there to let us in. And I did know how to say "please show me how to get to the toilet". Funny how easily that bit of Russian language came to me...

Our woman friend was by then very friendly. I'm sure she could see how cold we were and she was more than sympathetic to my plight.

About the Museum

There was no doubting that we needed a guide to have any idea about what we were looking at. Later, I looked up the museum on-line but there was only limited and very sketchy information available. The following is what I found.

Apparently the museum, which occupies an area of some 11.5 hectares, was the first open-air museum created in Yakutia (and god forbid, we know why!). Founded in 1977, it was created by the Tattinskiy community as a memorial for those politically exiled during the revolutionary period of the Tsarist era. The so called "prison without bars" represents all three stages of the revolutionary movement - the Decembrists, the Raznochinsy and the Social Democrats**.

The museum is a single exposition with yurts and houses in which the exiles once lived. The two beautiful wooden churches are also located on site, the main one being the Tattinskiy Nicholas Church which was built in the beginning of the 20th century. A lot of the structures were relocated from nearby villages, having been donated by local Yakut families. The site demonstrates the immense hardships of those exiled in the brutal Yakutian environment. Like Stalin's gulags, it was a natural prison where no physical barriers were needed.

The museum is not only dedicated to those exiled but also to the history of early Yakut life during the 1700's and 1,800's.

**The Decembrists were Russian revolutionaries who led an unsuccessful uprising on December 14, 1825, and through their martyrdom provided a source of inspiration to succeeding generations of Russian dissidents.

The Raznochintsy of the late 1880's were defined as those who were part of the Russian intelligentsia and who were declared as revolutionary thinkers.

The Social Democrat Party was a revolutionary socialist party founded in Belarus in the late 1800's. Formed to unite the various revolutionary organisations of the Russian Empire into one party in 1898, the RSDLP later split into Bolsheviks (majority) and Mensheviks (minority) factions, with the Bolshevik faction eventually becoming the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

The Raznochintsy of the late 1880's were defined as those who were part of the Russian intelligentsia and who were declared as revolutionary thinkers.

The Social Democrat Party was a revolutionary socialist party founded in Belarus in the late 1800's. Formed to unite the various revolutionary organisations of the Russian Empire into one party in 1898, the RSDLP later split into Bolsheviks (majority) and Mensheviks (minority) factions, with the Bolshevik faction eventually becoming the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

About an hour after leaving us at the museum, Yura returned. He looked a bit surprised that we had not "walked all the territory" of the museum but it was a bit too complicated to explain. He must have however, noticed our sour disposition. "My friend tells me there is a festival in Cherkekh. Perhaps we should try to find it?" Yura suggested. To our relief we didn't find the festival, just a little church and apparently there were some ice carvings further down the road. To go to the ice carvings, we would have to pay an entrance fee. Yura wasn't too keen and we politely declined.

Through Tattinskiy Ulus and Toward Khandyga

At a total of 19,000 square kilometers, Tattinskiy Ulus is larger, less populated and colder than the two ulusy we had travelled through on the first leg of our travels. Like the other two regions however, it is also flat with the main economy based on agriculture. Again, the population is overwhelmingly Yakut, comprising more than 95% of the total inhabitants.

The last part of our travels through the Tattinskiy Ulus took us through icy taiga vegetation past the main administrative centre of Ytyk-Kyuyol; a journey reminiscent of our trip through the frozen larch forests to Anabar. Here is a video of our trip through a lonely stretch at the end of the Tattinskiy Ulus: https://youtu.be/OomgzsexgKM.

Over the Aldan River to Khandyga

Late in the day we reached the Aldan River of the Tomponskiy Ulus and the frozen zimnik crossing to Khandyga.

In the long shadows of a perfect afternoon, the frozen river was truly glorious; the late glow of a subsiding sun illuminating the snow-coated, boulder strewn river surface. Breathtakingly beautiful, it was also breathtakingly cold. Again we cursed not having a thermometer but from our conversations with Yura we guessed it must be around minus 45 C. Here is a video of our trip across the zimnik: https://youtu.be/OomgzsexgKM

We finally arrived in Khandyga in the early evening. Hardly a welcoming sight, the drab main street was lined with grim Soviet styled buildings and crisscrossed by lagged water pipes for heating the town's homes.

Thick black smoke belched from the nearby coal-fired power station. After our extensive travels throughout the Russian Far East however, we had long stopped feeling dismay at the sight of the power stations. They were in fact, the life blood of the towns and without them there would be no settlement at all. In fact, I had grudging come to like them; a feeling of warm reassurance more likely....

It is always difficult for us to find private hotels in Russia. Mainly because like shops, there is nothing to identify them. For foreigners that is. They usually look like an ordinary apartment block with no signage. And often the main "reception" is just a small solid door.

The reception is usually pretty unfriendly at first too and the Khandyga guesthouse was no exception. To begin with, that is. As we squeezed through the small entrance door with all our luggage, it was impossible to immediately take off our boots. Yes, they were covered with snow and ice but there was just no room for the three of us dressed in our heavy gear, all our suit cases and numerous overcoats, to take off our boots beforehand.

A large blonde-haired woman finally appeared, screaming at us (obviously) not to walk in and over the carpet in our boots. And so, we all had to back out the small door until each of us took our boots off in turn. Alan was radiating a funny colour of angry purple but there was nothing we could do. Yura, like most Russian people we know, passively took it in his stride while Alan and I cursed, stumbling backward while we yanked off our heavy unobliging boots. On one leg....

Our room however, was fine. Typical of a lot of Russian hotels, it was furnished with brightly coloured red and black carpet, floral wallpaper, tizzy curtains and loudly coloured bedspreads. It was however, spotlessly clean and pretty comfortable. And of course, like all Russian buildings, it was very well heated.

A shared toilet was just outside our room and a communal kitchen was well equipped with cooking facilities, and ample table and cooking ware. The bedroom opposite was occupied by four friendly highway patrol police. Yura had a room at the back of the hotel. We always hold our breath when we arrive at remote location hotels and guest houses. But we had to admit that the Khandyga Hilton was very adequate!

Yura quickly left us at our guest house while he took his car to a heated garage. In this severe climate, cars need to be left running or stay in heated quarters. There is an Arctic Russian saying "You turn off your engine. You pick your car up in spring". It is always somewhat of a surprise for us Australians and something we have never had to think about in our home country.

A Woeful Evening OR "Anyone for Chicken Hearts?"

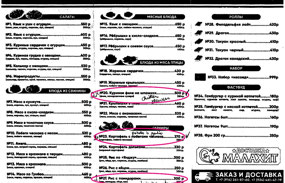

Later Yura returned with a menu from a local restaurant. A perfectly practical idea. We could translate the menu in the comfort of our room while enjoying a drink, chose what we wanted and Yura would order beforehand. There was however, a bit of a catch....

Arriving at the restaurant was not a great experience. A miserable green-walled box of a place, it sure lacked ambiance. Or comfort for that matter. The place was empty although it seemed to be doing an awful lot of take-away orders. We waited. And waited.

We had both ordered chicken fillet skewers, potatoes and rice. A seemingly straightforward order one would think. But there was a problem. Yura looking troubled, tried to explain as best as he could that our selection was not available. And this is where we did have a big problem communicating. I knew the word for chicken so I accepted the first menu item with chicken and a salad of some sort. Poor Yura was having all sorts of problems trying to explain but in the end, we agreed it was just best to go ahead with the Chicken Something and Unknown Salad. More annoying was that the waitress sometime after accepting our order demanded that we pay an additional 90 rubles each. We shrugged.

We must have waited nearly an hour before our meal was served. To our horror, our main meals were nothing but bowls of stir-fried chicken hearts, garnished with a little sliced chili and some carrot. And the bowl of hearts just sat there looking at us, complete with aortas and other vital bits of organ. Ughh... To his credit, Alan ate some of the hearts but after a few mouthfuls it was all too much. I couldn't bear to even touch mine. It was a very trying night, not improved by a furious Alan accusing me of eating most of the salad - which was probably true. The salad was I told him, awful anyway.

On our way back to our guest house, our thoughtful Yura pulled into a supermarket car park. What joy! Thankfully it was still open and there we bought some flat bread and some processed Viola brand cheese triangles. And so, we sat in our room dining on our frugal supermarket produce and enjoying a vodka or two. Bliss!

Later in the evening Alan began to suffer from urinary retention. Often an issue with artificial bladders like his, it can be caused by a number of factors including apparently severe body stress. We wondered whether it could have been the freezing cold conditions but quite frankly, we still do not know. Alan did recover from his problem but it was quite a scary experience. I am convinced it was the chicken hearts....

Khandyga, Sakha Republic, Russian Federation

Khandyga, Sakha Republic, Russian Federation

2025-05-23