On a Dark and Lonely Night....

In the steely darkness of a winter's night in the coldest village on earth, we stumbled through thigh deep snow toward a dimly lit building ahead of us.

A gentle voice called out "Добро пожаловать в Томтор. Очень, очень холодно! Скорее заходи внутрь!" "Welcome to Tomtor. It is very, very cold! Quickly, come inside!" It was Susan, host of Susan's Guesthouse - our accommodation for the next two nights in Tomtor.

We certainly didn't need any encouraging. At around 8:00 pm (or so we thought), it was very cold; around minus 35 C Yura told us.

We could not help but be immediately captivated by our warm and friendly host. And similarly her guesthouse whilst modest, was homely and inviting. The accommodation comprised a spacious lounge/living area with large lounges, tables and bookshelves, a number of bedrooms, a large kitchen dining area and a washing-come-banya (Russian sauna) room at the rear of the house. To our delight, there was an inside flushing toilet - a big plus in these icy environments. And even Wi Fi was available. Bliss!

As in many of these remote regions however, there was no running water. Cold water was supplied by blocks of cut river ice stored on the roof of the house where it was left to melt and flow down by gravity. Limited hot water could be obtained from the reticulated heating pipes within Susan's house.

Susan fussed around us, showing us the guesthouse facilities, then taking us to our room. Like all of the rooms at Susan's, our bedroom was adorned with flamboyantly coloured furnishing, floor covers and bedding, and was spotlessly clean. Two comfy single beds were piled high with additional blankets and doonas.

To our delight, we were the only guests for our two-night stay. Which was just as well as there was no way we could fit our luggage into our tiny room.

Delicious aromas of hot food wafted from the kitchen. A large dining table was already packed with breads, salads, chocolates and fruit. It was again, with another sigh of relief that we realised our accommodation in Tomtor would be very comfortable. But then again, our travel agent Ed had not let us down yet....

Susan did not speak English but we could understand she was asking us what time we would like our evening meal. "Is 9:00 pm convenient?" I asked in my best Russian. It had been common for us on our Arctic travels to eat a late evening meal and so we hoped this sounded like a convenient time for Susan - and which would give us a short time to unpack.

Susan smiled and nodded but I thought I noted a flicker of concern - or most probably confusion. However, it wasn't until a bit later when we looked at my phone, we realised with some shock that it was already 9:40 pm. We had absolutely no idea that as we entered Oymyakonskiy Ulus, that we had gained an additional hour.

Meanwhile, Susan had patiently waited for us in the dining area. There was no way we could explain our timing issue. Some things are just too hard to resolve - even with Google Translate.

Dinner was a traditional homestyle Russian meal with tureens of Susan's special Yakut soup and large platters of plov, meatballs, potatoes and salad. Blini with home-made berry jam and sour cream were served as dessert. It was just a pity that we could not chat with Susan over our meal. We did an awful lot of smiling and for me an awful lot of "Это очень вкусно!". "This is very delicious!" It was of course, tiring for everyone.

After dinner, Susan handed us her phone. A young woman who spoke perfect English welcomed us. "My name is Olesya and Susan is my grandmother. My husband Vasily and I live next door. If you need anything just phone us". And we did. Later that evening, Vasily kindly dropped into our guesthouse to organise our Wi Fi connection. Although he did not speak English, he soon worked out what our problems were and fixed it very quickly. We were very grateful.

I must say, it was quite a relief to have English-speaking Olesya nearby. And as it happened, we did need the couple on quite a few occasions during our short stay.

A DAY IN THE COLDEST SETTLEMENT ON EARTH

A New Day Dawns in Icy Tomtor

Olesya had informed us the evening before, that as we would have the luxury of a slightly later start to the following day, there was no need to get up too early. It was kind of her and good news for us. We were beginning to tire from our weeks of long journeys. And I am sure that Yura would have been pleased too. After driving 2,000 km non-stop for three days, he must have enjoyed the time to rest for a while in his home in the village of Orta-Balagan, some 40 km east of Tomtor.

We awoke the next morning to the soft padding of Susan's slippers. Taking super care not to disturb us with her breakfast preparations, she had carefully closed our bedroom door in order not to wake us. Susan really was a very thoughtful host.

Breakfast was again a filling meal of meat balls, potatoes and piroshki. But we had at last heeded Ed's warnings about not eating heartily enough. Normally a bowl of fresh fruit is all we have for breakfast. But there was no doubt that in these extreme cold climates we did need a substantial breakfast, despite our fears of the effects it was having on our waistline. Funnily enough, to our surprise neither of us seemed to put on any weight during our travels.

It is hard to believe that we could feel that Oymyakon was any colder than the places we had visited during our Anabarskiy tour. But it certainly was. And although Susan's house was well heated, we had found it necessary to wear our thermals to bed. We were also very mindful of how easily it had been for us to become seriously cold in Oymyakon, despite all Ed's warnings.

Our Day's Plans and a Word About Susan's Guesthouse

And Ed was right again. There was really not a lot to do or see in the Oymyakon district. The good news however, was although it held the dubious honour of having the coldest recorded temperature of any settlement in the world, it did not appear to be at all touristy - something about which we had been concerned when we chose to visit Oymyakon.

After Alan's retention problems a couple of days before, we were forced to re-think how much cold he should endure and of course how much time he could spend outside. For that reason, we had immediately cancelled our plans for ice fishing but had opted, if a bit reluctantly, to fulfil our commitments to visit a local horse herder's farm. We would however, have been just happy to spend our only day in the Oymyakon area looking at the villages and discovering how people living in such an extreme climate, went about their daily lives. And after all, we had visited a Yakut horse herder's property for a day in Sinsk. And I had owned and ridden horses all my life....

Olesya phoned after breakfast explaining to us that we would be visiting our horse herder's place at Balagan that morning, and in the afternoon a short tour around Oymyakon village and surrounds. It was she insisted, absolutely vital that we wore the warmest clothing we possessed. We took her advice seriously. Even still, our motherly host Susan was not convinced we would be warm enough, frowning at our clothing and murmuring in Russian.

At 10:00 am, Yura arrived looking considerably refreshed. Before we headed off we had a quick look around the outside of the guesthouse.

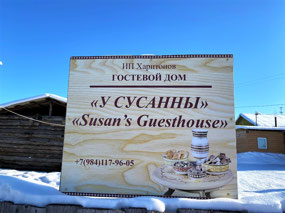

In the glowing radiance of a brilliant sunny but deceptively bitterly cold day, we could for the first time have a look at Susan's Guesthouse from the outside and also surrounding the tiny snow clad village of Tomtor. Even from the outside, the guesthouse which was solidly constructed from heavy timber was well maintained and inviting. A large sign outside "Susan's Guesthouse" was labelled in both Russian and English.

Olesya had explained earlier that the guesthouse was a family business established with input from a small number of other private sources. Susan's Guesthouse she said, had been apparently running for many years, successfully welcoming guests from all over the world.

Both teachers, Olesya and Vasily were helping Susan with the business for the two years they lived with their young daughter Vasilina at Tomtor.

It was without doubt that with Olesya's excellent English and Vasily's "fix it" skills, they were great asset to Susan and her business.

A Glance of the Oymyakonskiy Ulus. The Mythical Labynkar Monster

Oymyakonskiy Ulus like other numerous ulisy through which we had travelled, is one of 34 districts or rayons in the vast Sakha Republic. It borders with Ust-Mayskiy District to the south-west, Tomponskiy District to the west, Momskiy District to the north, Magadan Oblast to the east and Khabarovsk Krai in the south. The area of the ulus is a considerable 92,300 square kilometers, almost the size of Hungary.

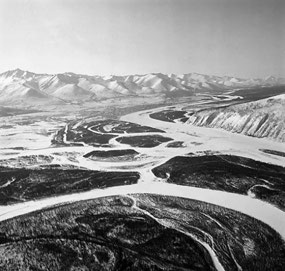

The landscape of the district is mostly mountainous. The Nera Plateau located in the eastern part of the district, the Tas-Kystabyt Range in the centre, the Oymyakon Highlands and Elgin Plateau in the west, the Suntar-Khayata Range to the south-west and some of the Chernskiy mountain system to the north. Interestingly, despite its severe climate and mountainous landscape, a large part of the district is covered with taiga forest interspersed with areas of steppe country.

Rock pillars also are a curious feature of this wild landscape.

The main river is the Indigirka. At 1,726 km in length, it is the main waterway of the Oymyakon Plateau and one of the largest rivers in the Russian North-East. The Oymyakonskiy ulus like all permafrost regions, is dominated by numerous lakes; the Labynkar Lake being the most famous for its mythical Labynkar Monster.*

Oymyakonskiy is a very sparsely populated district, with around only 10,000 inhabitants. The administrative centre is Ust Nera which accounts for the vast majority (70%) of the population. The demographics comprise Russians (53%), Yakut (29%), Ukrainians (6%) and Evenks (4%).

The population like many of those in the Far East, has reduced significantly in more recent years; from 1989 to 2007 declining by some 55%. Information about Oymyakonskiy (even on Russian search engines) is very sparse but the fall in population is most probably due to the 1991 economic crisis after the demise of the Soviet system, as well as a general decrease in mining activity.

The economy of Oymyakonskiy today is mainly mining (diamonds, gold, silver, tin, tungsten, lead, zinc, antimony) and agricultural industries of horse and cattle raising (meat and milk) and reindeer herding (meat and transport)

Russian explorers first travelled through this region down the Indigirka River in 1641. Much later expeditions began flying in by hydro-planes exploring the area for minerals.

Oymyakonskiy Ulus was established on 20 May 1931 during the Soviet Stalinist era when forced gulag labour was used to extensively mine the region.

During the Great Patriotic War (World War II), the area was widely mined for the much needed tin and gold. An airfield was established in the district of Aeroport for the Alaskan Siberian air route, used to ferry American Lend-Lease aircraft and supplies to the Eastern Front.

*The Mythical Labynkar Monster

"Taking on more notoriety than the Loch Ness Monster, the 'creature' came to be called the Labynkyr Monster by cryptid enthusiasts internationally and was said to have a body shape more resembling an elongated lizard than a fish. It was described as having short legs, and an exceptionally long tail. Eventually somebody called it a giant monitor lizard and the description gave way to speculation that the Siberian Lake Devil was in fact a long extinct prehistoric monster of a lizard known as the Mosasaur.

Aside from the fact that Mosasaurs went extinct seventy million years ago, there was one other major problem with this connection, Mosasaurs were warm water creatures. The idea that this dinosaur was still alive was as impossible as it having ever existed in this part of the world, except that Lake Labynkyr is itself an anomaly. It is a lake in a frozen wasteland that never freezes and has been the subject of numerous scientific examinations for this reason as well....." (Wiki Fathom)

Oymyakonskiy Climate.

The climate of Oymyakonskiy is described as Extreme Subarctic (Köppen climate classification). Winters are severe with average temperatures from December through to February under minus 50 C. Interestingly, Oymyakon and neighbouring Verkhoyansk (625 km north-west) are the only two permanently inhabited places in the world that have recorded temperatures below minus 60 C for every day in January. Yes, it's SERIOUSLY COLD!

Conversely, while winters are bitter and extremely long, summers are mild to warm; sometimes even hot. In June, July and August it is not uncommon to have temperatures over plus 30 C; the highest recorded temperature being 34.6 C, yielding a temperature range of more than 100 degrees C!

Precipitation is very low, with the average annual rainfall being only 215 mm or 8.5 inches. An Arctic Desert really - but like other extreme cold regions in the Russian Far East, most free water is due to snow or ice melt. And with a permafrost environment, drainage is almost zero resulting in vast muskeg and numerous lakes. Similarly, as monthly temperatures are below freezing for several months of the year, evaporation only occurs in the summer months.

Interestingly, despite the extreme cold climate there is quite extensive taiga vegetation at Oymyakon. This fascinating phenomenon is a direct result of the extremes of temperature, with plants such as the sturdy larch species being able to photosynthesise sufficient nutrient in the small window of summer warmth to sustain them through winter.

A Perfect Storm for the Most Extreme Cold in the World

Oymyakon is located at a latitude of 63.46° N. Whilst it is relatively far north, it sits below the Arctic Circle, and is certainly not the most northern region in Russia. There are many settlements further north which do not share the same degree of cold. For example Yuryung-Khaya, our final destination of our Anarbarskiy journey is located at a latitude 72.0° N or well over 900 km further north of Oymyakon.

Why then is Oymyakon so cold?

The explanation lies in both the geography of the district and the phenomenon of what is known as the Siberian High, a semi-permanent ridge of high pressure that stabilises over the region for much of the winter. Unlike other regions in the world with semi-permanent highs, Oymyakon is not prone to storms which can flush out the cold air and mix it with warmer currents.

Instead, the Siberian High steers storms away ensuring there is no warm air flowing in; thereby creating a self-perpetuating influx of frigid air and a self-reinforcing cycle of deepening chill.

To further exacerbate the situation, Oymyakon is a landlocked region located in the heart of eastern Siberia, one of the coldest regions on the planet. It is also located between two valleys which acts as a magnet for climatic inversions; a process where cold air sinks to the valley floor while warmer air rises and acts as a cap to keep the cold air in. Hence, Oymyakon is not only the coldest region permanently settled but it also boasts the longest, continuous cold cycles known.

Together, these phenomena are a "Perfect Storm" for ensuring Oymyakon remains the coldest settlement on the planet.

A Visit to the Horse Herder

Aleksandr's horse farming property at Balagan was a fifteen minute drive from Tomtor. We began our journey travelling along the Old Summer Road; firstly crossing a bridge over the Kuydusun River, a tributary of the mighty Indigirka, then following the wide flat road through some very pretty taiga woodland. We were very fortunate that it was such a glorious day as it sure was deceptively freezing outside. Even still, the temperatures for Oymyakon were not extreme; around minus 30 Yura thought.

Situated in an isolated location well off the Old Summer Road and looking somewhat like a Swiss chalet in design, Aleksandr's house was solidly constructed from heavy timber and surrounded by equally sturdy wooden fencing. Out of the front of the building lie massive cubes of ice cut from nearby Kuydusun River for use as drinking water, and a heap of chopped logs for heating. The amount of physical work in chain sawing the ice and cutting the logs would have been extraordinary.

We recalled Ed's parents-in-law with whom we had the fortune to meet and stay with in Sinsk on the first leg of our Anarbarskiy journey. Ed had told us that until the very recent advent of central heating, most of his father-in-law's life in summer was taken up preparing wood for winter season, and then in winter sawing chunks of ice on a regular basis from the river for their water supply. It was sheer hard physical work. But heat is life in these extreme cold regions; and a life here is certainly not for the faint-hearted.

And this time we left no chances to the cold. Donning all our cold weather gear was as usual, not a lot of fun with Alan cursing and swearing that he couldn't get his mittens on over his thermal gloves. Meanwhile Yura patiently - or pityingly - looked on.

Aleksandr was there to meet us. A diminutive, friendly man who apparently spoke no English at all, explained somehow through Yura that he was a former jockey who had turned to raising horses for a living. Looking out onto his large herd, we were saddened with the knowledge that most of the little Yakut ponies were destined for the slaughterhouse. As mentioned, it was something about which Alan and I squeamishly never felt at all comfortable.

We had visited another horse herder property (refer "Snowmobile Trip to the Horse http://v2.travelark.org/travel-blog-entry/crowdywendy/13/1590139588) on our Anabarskiy journey and were in awe of these cute woolly ponies that must be some of the toughest horses on earth. At around only 13 to 14 hands high (or around 140 cm from

hoof to withers), the ponies looked to be put together by a committee with a

great sense of humour. Coarse-headed with upside down necks, pointy rumps and

stumpy short legs, they were at the far end of the bell-shaped curve of equine

beauty. But I had to

totally admire these hardy little fellows, with their lovely nature and adorable

sweet faces.

The Yakut horse is thought to be related to the robust

Mongolian Pony and also the much famed ancient Przewalski's Horse of southern

Russia and Mongolia. They have ingeniously adapted to the harsh cold

environment; being able to forage out vegetation buried deep beneath the snow

and by developing unique morphological adaptations to the sub-Arctic climate.

They have acclimatised their requirements in line with seasonal phases by accumulating high fat levels during the short vegetative growing season and lowering their metabolism in winter. Furthermore, they grow extraordinarily thick coats in winter. These horses exist with no shelter and their ability to withstand such climate extremes is nothing short of miraculous.

In Sakha, the Yakut horses are used as an

important source of meat protein, as well as for transport. Like our first horse herder Yuri, Aleksandr was keen to tell us that Sakha people never eat working horses.

Yura left us to talk with Aleksandr while we ploughed around the manure-laden paddocks talking to the ponies. Yura had asked us whether we wanted to ride but it was so cold that even for me it was totally out of the question. Needless to say, it certainly wasn't on Alan's agenda. As he always said, having trudged around behind me for years while I was actively competing in equestrian events, he had had enough of horses to last him a life time....

The ponies were all in good condition and were extremely inquisitive and friendly. One little buckskin coloured fellow was particularly friendly and followed us everywhere; the rest of the herd followed warily.

Much as I adore horses however, a half an hour of pony watching and taking photos in temperatures of around minus 30 C was quite enough. I was hoping that Aleksandr may tell us something about himself and his life in remote Oymyakon but of course neither he nor Yura spoke English. Even a cup of coffee and an opportunity to sit down and warm up would have been nice....

We left soon wondering what the hell we had been doing there, let alone paying 6,000 rubles for the privilege.

To Oymyakon Village

After another substantial meal at Susan's, we were off on our afternoon visit to Oymyakon village, some 30 km north-west of Tomtor on the Old Summer Road.

As mentioned, the Oymyakon district comprises a cluster of several small villages, including the village of Oymyakon, known as a rural locality or "selo". The village lies on the banks of the Indigirka River. It's very name is apparently is derived from the Even word for "unfrozen patch of water; place where the fish spend winter." And as we were to find, there are areas along the river that never freeze; all kept above freezing point by underground thermal activity. But only just above freezing as a friend was to find out....

With a tiny population of just 500 permanent residences, it is this village which is the most famous for being known as the Pole of Cold, having recorded a gob-smacking temperature of minus 71.2 C in 1924. Mind you, one would wonder at the accuracy of thermometers in 1924.... But it's a good story and anyway, it obviously was an astonishingly cold night.

Interestingly Oymyakon village despite only having a population of some 500 permanent residents, was larger than what I had imagined. As our little vehicle ground its way through the snow-engulfed main road, we noted that many of the houses were of a reasonable size; steep roofed, chalet-style buildings constructed from substantial timber slabs. On a typically chilling yet windless winter day, chimneys spewed out vertical columns of thick white smoke against a white featureless background.

From the main street, the village appeared just as a cluster of dwellings with no rhyme nor reason as to their positioning; the meters-deep snow masking any semblance of structured roads or footpaths.

As commonly encountered in these tiny Arctic villages in mid-winter, there were no people, no animals nor even any other vehicles to be seen. The streets were seemingly completely devoid of life; the all too familiar noise of our car tyres crunching through the snow being the only sound to be heard. Here is a video of what we saw: https://youtu.be/qi_8hfuWX_s

In 2015 photographer Amos Chapple's described his experience in Oymyakon village "The streets were just empty. I had expected they would be used to the cold and there would be everyday life happening in the streets, but instead people were very wary of the cold. It felt extremely desolate but it wasn't... Everything was happening indoors, and I wasn't welcome indoors. I spent hours wandering the village streets; my main companions street dogs or village drunks...." (Natasha Geiling, Smithsonian magazine).

This was a familiar experience for us. The very sensible local people know full well the seriousness of extreme cold. The children too are cautious. In the many places we have visited in winter, the streets and even the playgrounds were often empty. And where there were people, it was a common occurrence for us complacent foreigners to be approached by complete strangers who may have noticed that our coat zippers were perhaps not quite done up, or that we had dropped one of our mittens.

In such cold, water thrown into the air can freeze before it hits the ground. Even vodka and diesel can freeze. And clothes hung out to dry can readily freeze and snap apart. Cold is a deadly serious issue in the Extreme Arctic.

But life does go on. Farmers apparently have to bring their cows to the village's watering hole, then lead them back to their insulated stables. And schools don't close unless temperatures fall below minus 50 C. Cars must be kept running or be housed in heated garages. And from what we saw, many of the homes still have outside toilets. They are a tough lot in this region.

Apart from some monuments to commemorate the record-breaking temperature of 1924, contrary to our initial fears, there was little to suggest that this village was in any way touristy. To our relief it was, just an ordinary little village with an extraordinary world record.

Introducing Anders Biro....

I love meeting fellow travellers on the Internet. And many of our travel contacts have remained online friends for years. Largely because of the off-the-beaten-track destinations to which we usually travel, we are quite often asked questions through travel fora about our unconventional journeys. After all, there are few travellers to the Extreme Arctic, especially to the really remote regions of Sakha, Chukotka and the more northern areas of Magadan. And not surprisingly, very little travel information is available. But as warm-climate dwelling Australians, we were certainly not expecting to be asked about suitable extreme cold weather gear by a well-travelled young Swedish man!

In December 2019, just a couple of months before our departure another "Internet Travel Friend" Geoff Nattrass notified us about a Lonely Planet Thorn Tree inquiry from a Swedish man wanting information about the Extreme Arctic. Could he provide him with our contact details? Of course we agreed. Very soon, we received an email from Anders Biro who was about to embark on his first journey to Siberia. Somewhat amused that anyone would think of asking us Australians, we sent him a comprehensive and detailed list of clothing and other information that our very thorough travel agent Ed had sent to us prior to our travels. Like all of Anders' correspondence, his reply of thanks was prompt and polite.

Busy with our travel arrangements, we didn't think about Anders until he contacted us from Yakutsk to say he was confident his clothing would be adequate for his needs in Oymyakon. After all, as he said - it was a balmy minus 35 C!

Following Anders' Arctic journey on FaceBook, we were somewhat gob-smacked however, to read that he had taken on a promise to a Swedish friend that he would jump into one of Oymyakon's thermal pools on Christmas night, and of course in the middle of Oymyakon's frigid winter. The video footage was very amusing. On a minus 52 C evening, prior to his freezing plunge a pale, semi-naked Anders jogged for a few minutes through the snow clad village waving a Swedish flag and wearing nothing more than a pair of shorts and snow boots, topped by a ridiculous Santa hat.

Why would anyone undertake such a crazy act? Well, best to ask Anders about that one....

Anders explains: "I do not know really how to summarise my person, but I guess that the reason I ended up in Siberia in the first place is that I have this inner compulsion to see exotic places. I guess it all boils down to that I as a child read too many adventure books, and in a sense it permanently shaped my idea about how real adult life should be. I suppose most people eventually mature to the conclusion that real adult life is not like in the TinTin albums and other stories, and it is really idealistic escapism from a grown-up reality that is way duller, but somehow I got stuck in denial and I am still pursuing this transforming adventure....

I guess that provides some context as far as motivation goes as to why I ended up winter bathing in the coldest inhabited place in the world...."

As it happened, our Anders was not aware until the last minute that the so-called "thermal pool" was not quite the balmy waters he thought. And that in fact the water temperature was only just above freezing. "In a way it was a bit sad that I learned about it (from his taxi driver) just before the actual bath, because the video may have been improved by my shock of realising it when I hit the water...." Here are two videos of his chilly adventures: https://youtu.be/bIrMOMUvqDU and https://youtu.be/qszK1n39tis (kind courtesy of Anders Biro).

Obviously impressed, his taxi driver told him that Mr Putin would certainly hand him a Russian passport as he obviously had what it takes to be a Russian!

Anders summarises: "As far as travelling goes.... when people ask me why I expose myself to such discomfort in my travels, my answer is 'Either you understand, or you don't'".

Anders' attitude to travel certainly resonated with us. We are asked that question over and over again, only these days with an additional "at your ages" thrown in for good measure. You are right though Anders. Either you get it. Or you don't.

I'm not so sure however we would ever contemplate Anders' antics....

Notes: Photos and videos kind courtesy of Anders Biro.

A Visit to the Indigirka River Thermal Springs

From Oymyakon village we followed the Indigirka River zimnik north some five km or so to some thermal springs. Wandering around the area, I thought of Anders and wondered whether this was the spot where he had undertaken his mad Christmas bathing exercise. Even on a beautiful sunny day, the water with its surrounding ice river banks, looked forbidding. It was unbelievable to even contemplate bathing here on a frigid minus 52 C night....

Certainly others had been there before us, leaving rubbish and cigarette butts in what looked like a former camping area. It was disappointing. Surely people came here for the same reasons as us - to see what it was like to be in the coldest inhabited, pristine region on the planet. Their thoughtlessness was hard to believe.

Yura explained as best he could that these "thermal springs" never freeze and the water is so clean it is used untreated as drinking water. Apart from the campers, the area was splendid; perfect brilliant, pearly white ice and deep clear water springs.

On our way back to Tomtor, Yura stopped at a dairy farm at the tiny village Bereg-Yurdya to pick up some kumys and sour cream that Susan had asked him to buy. The village from where we sat in the car looked fascinating. Again, there was no sign of human life but plenty of ponies and cattle. And from what we could see, were stables and cattle sheds to house the animals in the evening. We would have loved to visit the farm but it was all too difficult to translate.

A Shopping Experience in Tomtor

Late in the afternoon we returned to Tomtor. Somehow I found it surprisingly easy to ask Yura in Russian about buying some alcohol. "No problems", smiled Yura characteristically.

But it sure would have been a problem without Yura. The "shop", like many we encountered not only in Russia but also in other cold climate countries such as Mongolia, was impossible to recognise as any sort of store, let alone a liquor shop. There was no signage that we could see and with heavy solid doors and no windows, the premises didn't give much away as to what was on offer in the shop - or indeed, whether it really was a shop. In such extreme climates there is no such privilege of being able to look in from the outside.

Nevertheless, we bought what we needed and marched off happily with our supplies that would at least get us back to Yakutsk.

We spent a short amount of time looking around Tomtor, home to some 1,200 permanent residents. Again, it was a truly fascinating village and perhaps a place where we should have spent some more time. There was a real feeling of pride with brightly coloured dwellings appearing to be well maintained and in fine order. A number of monuments commemorated the record-breaking 1924 temperature.

On a very cold nightfall, we returned to Susan's warm and homely guesthouse. She had again prepared another enormous evening meal of borscht, meatballs, fish and potatoes. Hard as it is to believe, after a day in the cold, we were starving hungry and thoroughly enjoyed our meal. Susan was beginning to look pleased with our appetites.

Later in the evening, Vasily dropped in to help Alan with a problem zipper on his coat. A seemingly small issue of being unable to zip up a coat, in these extreme temperatures is not just an inconvenience, it can be a very serious problem. Again, we were very grateful.

We enjoyed an early night, sinking into our thick comfy doonas - well rugged up in our thermal nightwear.

Despite our initial reservations, our trip to Oymyakon district had been an interesting and very pleasant experience. And sadly, now there was just a 1,000 km return journey to Yakutsk via Khandyga before our Extreme Russian adventure would come to an end.

Oymyakon, Sakha Republic, Russian Federation

Oymyakon, Sakha Republic, Russian Federation

Danil Alekseyanovich

2022-02-01

a good time to visit my home of Oymyakon is on New years (Jan. 7th) you will see people out and about celebrating the event, but we're mostly indoors 95% of the time cause we take winter seriously here it only takes 1-3 minutes before you start showing signs of frostbite (nose turns pale). I highly recommend you come to our Yhyakh festival in Yakutsk June 21-22. May change if covid still a pandemic in region.