Arriving in Resolute

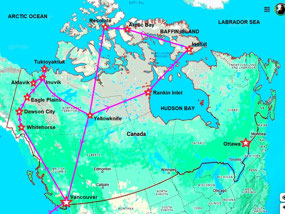

Resolute was the raison d'etre for our journey to the Canadian High Arctic.

At a latitude of 74.6973 °N, it is one of the northernmost inhabited settlements in the world. Following Longyearbyen in Svalbard, it was the second most northerly location we had visited. After so many trips to Extreme Arctic Russia, Svalbard, Greenland and now the Canadian High North, we had become true polar tragics.

It was hugely exciting to arrive at our ultimate destination, Resolute. On the "Edge of Nowhere", Resolute is also famed as a launching point for an eclectic mix of extreme adventurers and explorers travelling to the North Pole. It is a hub for charter flights throughout the rest of the High Arctic, and also for those flying to the meteorological and military settlements of Eureka and Alert. "How much more exciting could this be?" we asked ourselves.

From my first step on its frozen, lunar-like surface, I fell in love with Resolute. On a bitterly icy cold and windy day, it was still a mind-blowing experience. Being so far north, there was no vegetation - just a mere huddle of dwellings and a seamless transition between land and the frozen sea - polar nowhere.

I considered our fortune. After all, how many people have been to Resolute - or Nunavut, for that matter? I smiled. How many friends and acquaintances would add, "And who in the right mind would want to....?"

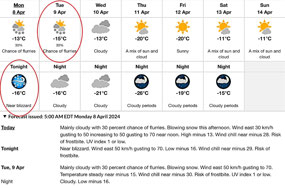

Unlike our arrival in Arctic Bay, the weather was stormy, snowing and blowing a gale. Sadly, limited visibility made taking photographs on our descent into Resolute impossible. Snowstorms in Iqaluit resulted in our flight from Arctic Bay being late. We were incredibly lucky, however, that the continuing poor weather had not prevented our safe landing in Resolute. Flight cancellations are more of the "norm" than an exception in these locations, and there have been some terrible accidents in past years.

In the high Arctic, we always add a few days of "buffer" at the end or beginning of our Arctic stays. Our buffer on this occasion was the extra time we allowed for our return visit to Iqaluit. Still dejected about our miserable stay in Iqaluit, my thoughts wandered to the less helpful side of my brain. Perhaps, we might get snowed in, in Resolute? Sadly, I knew it was just wishful thinking... I didn't mention my thoughts to Alan. Well, at least not then...

Our arrival was a very social and animated affair. Dorothy, one of the senior administrators from our South Camp Inn, found us immediately. And although they were (disappointingly!) not dressed in the old television series Royal Canadian Mounted Police red jackets and jodhpurs, we also found Quentin and Paul, who Steve from Arctic Bay had kindly contacted prior to our arrival. To our delight, Quentin offered to take us on a tour of Resolute and would call us the next day. Warm and friendly, it was a great welcome to this much-anticipated visit.

Also at the airport were a delightful young couple, Makpa and Sheldon. They met us because we had inquired about a possible trip to view polar bears with a local tour guide.

We had however, not confirmed our tour because of the gob-smacking price quoted of CAD $2,000 per day for the two of us. Furthermore, now that Alan was "black-banned" from riding snowmobiles, it probably was not a good idea to tempt fate again.

But then again, while we were on our once-in-a-lifetime visit to Resolute... For people who had not organised anything, we were inundated with activities.

To Our South Camp Inn Hotel

The ATCO* South Camp Inn is the only accommodation in the central part of Resolute. Fortunately, it was excellent. It is not cheap, and at a colossal cost of almost AUD 1,000 per night for the two of us, it needed to be excellent. But it was full-board and included all meals. We laughed when we read the Nunavut travel guide "Travel Nunavut" to see if there was anywhere else to eat. It had listed Resolute's recommended restaurants and cafes as "None."

Our room looked out onto the beautiful frozen expanse of Resolute Bay. It was spacious, comfortable, and equipped with everything we needed. South Camp Inn was surprisingly large and sophisticated, with a commercial kitchen, spacious dining rooms, lounge and sitting areas, and laundry facilities.

But then again, it was home to 22 full-time ATCO employees who worked on a rotational "eight-week on, four-weeks off basis". Employees were transported to and from Resolute by charter flight at discount rates to Yellowknife, where they organised their travel back to their homes.

Concerned that we missed lunch, Dorothy had arranged for two enormous plates of lasagna to be put aside for us to reheat when we wanted. Friendly, thoughtful and highly professional, Dorothy contributed very much to the enjoyment of our stay at South Camp Inn. In fact, all the staff was terrific.

*Note: ATCO is a Canadian engineering, logistics, and energy company based in Alberta, Canada. It is a publicly traded company that operates worldwide. In Resolute, it is responsible for water and wastewater treatment, fuel delivery services, facility maintenance, the annual Sealift, and snow removal. It operates the South Camp Inn and ATCO Lodging at the airport (primarily for fly-in and fly-out individuals).

An Afternoon Shop at the Tudjaat Co-Op Supermarket

Late in the afternoon, the only thing we could do was find the Tudjaat Co-Op Supermarket. What else would one expect of us? Resolute was also a "dry community," so we resigned ourselves to buying soda water and stocking up on snack food supplies. It was really just an excuse to visit the supermarket.

Fortunately, the weather had improved, and our short walk across the road to the shop was pleasant. The store was not quite in the league of the other Arctic departments we had visited, but then again, they were catering for a population of less than 200 permanent residents. ATCO employees and hunting tourists would have been fully catered to while boarding the South Camp Inn.

On our return to our hotel, we were admiring a particularly flashy, iridescent blue snowmobile when the owner came up to chat with us. He said the vehicle was brand new, and he was obviously very proud of his purchase. Welcoming and friendly, he was typical of the locals we were to meet during our Resolute stay.

Evening at the South Camp Inn

Meals were a casual and social affair. Chef Paul produced an impressive array of well-prepared meals, always with several meat, fish, and vegetarian options.

And there were always homemade soups, plenty of vegetables and salads, and desserts. And always, a few extra touches. The quality of the meals was excellent.

There were regular meal schedules, but at any time, we could come to the dining room and help ourselves to tea and coffee, cakes, sandwiches, croissants, ice cream, or fresh fruit, which was always abundant. The logistics of managing all this food, which, of course, had to be ordered and flown in each week, must have been a nightmare.

With ATCO workers, administration staff, and visitors, Paul catered daily breakfasts, lunches, and dinners to 30 to 40 people. From what we gathered, local people could dine there as well. The ATCO workers were from all over the world and extraordinarily friendly.

Once again, we appeared to be the only non-hunter guests, and people were curious about who we were. We were pretty old and obviously not on business... What were we doing in Resolute?

The latter question was not the easiest to answer. And in hindsight, I think they meant, "How could we afford it?" It was worrying us, too... I don't know how often we said to each other, "Well, it's a one-off experience. And we will never be here again." But we said that on nearly every one of our last fifteen trips...

We felt very much at home at South Camp. Our evening meal was very good, and the camaraderie was pleasant. It was, we agreed, a fine start to our stay in Resolute.

DAY 2

Unplanned Activities

Quentin rang us mid-morning, offering to take us for a drive around Resolute in the afternoon. Although the early morning weather was extraordinarily cold and windy, he thought the conditions would improve. We were delighted.

Makpa and Sheldon also visited us, suggesting we undertake a snowmobile trip on Resolute Bay the following day. The weather conditions were forecast to be almost perfect. They were also confident we would see polar bears. We thought that polar bears would be in hibernation at that time of the year, but apparently not...

At CAD 2,000 per day for the tour, we simply could not justify the cost. "Well, how about half a day then?" suggested Sheldon. We were hardly getting a bargain at CAD 1,000 for half a day. But Sheldon was not in a position to negotiate. He worked for an outfitter's company in Resolute. And even without giving us a discount, he had to check with his boss to see if a half-day tour would be OK.**

I was also worried about Alan's shocking Arctic incident and snowmobiling accident record. Apart from rolling his snowmobile on two occasions, falling backward on an icy road and splitting his head open, he had also suffered acute dehydration and collapsed on several occasions when we were outside in Greenland, the severe cold appearing to be a catalyst to his vertigo. Hospitalised twice on that trip he was, we agreed, a polar liability! It was a miracle that he would even consider any more outside Arctic activities...

But of course, we couldn't resist...

Sheldon assured us we would be pillion snowmobile passengers with him and Makpa. He would also ensure that we often stopped to check Alan's health and comfort. And so, despite saying after the Yellowknife incident, "No more snowmobiling for Alan," we once again made a somewhat reckless decision to go against every aspect of logic and reasonable behaviour. It was nothing new for us...

** We had also inquired about a polar bear viewing tour in Arctic Bay. At CAD 2,000 per day, we considered the price outrageous. And it was... We were so shocked that we gave it a miss. Surely this travel agent was ripping us off? But as we were to discover, these are going prices in the High Arctic. We hadn't realised that these "travel agents" were outfitters who guided wealthy hunters. We certainly were not into killing bears, just viewing them! But it sure was a sellers' market.

A Change of Mind

Late in the morning, much of my elation from being in Resolute had begun to evaporate. Miserably, all I could think of was our coming trip to Iqaluit. Five days there when we could be in lovely Resolute seemed crazy. Well, maybe the extra cost didn't...

Alan felt the same. And so, we decided to extend our stay in Resolute for another three days. Dorothy assured us we were in luck. Unusually, our room was free during that time. But when it came to rescheduling our Canadian North flight, our plans were hit a massive blow. The process would cost us nearly CAD 2,000 in fees to change our flight. Given the additional costs of CAD 3,000 for three extra nights of accommodation at Resolute, we would be up for another CAD 5,000. Sadly, there was no way we could justify extending our stay.

"Things always turn out for the best," said Alan. It was an irritating cliche that annoyed the life out of me. Even more infuriating, he was nearly always right...

We quickly shook ourselves out of our self-pity. After all, we were so lucky to even be in Resolute And at least the weather was clearing for our afternoon tour

INTRODUCING RESOLUTE

At a Glimpse

Resolute or Resolute Bay, also known as "Quasuittuq" (literally meaning "Place with no dawn"), is an Inuit hamlet located on Cornwallis Island in Nunavut. It is situated at the northern end of Resolute Bay and Northwest Passage and is part of the Qikiqtaaluk Region. Resolute has a population of just 183 people (2021 census).

The Qikiqtaaluk Region (formerly known as the Baffin Region) is Nunavut's easternmost, northernmost, and southernmost administrative region. With a population of approximately 20,000 and an area of almost one million square km, it is the largest and most populated of the three Nunavut regions. It is the largest second-level administrative division in the world.

Early Days of the 19th Century

Resolute Settlement was named after a ship, the HMS Resolute, that had been searching for British explorer and seafarer John Franklin's lost expedition in the mid-1850s. An evocative name, Resolute conjures visions of tall ships, brave explorers, brutal weather and terrible Arctic seas. A perfect name, really...

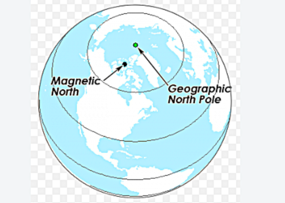

In 1845, Sir John Franklin's Arctic expedition sailed from England to find the Northwest Passage and record magnetic data for navigation through the Canadian Arctic. The expedition failed. Cornwallis Island was one of the last known places that Franklin circumnavigated before his expedition sailed south and was lost forever.

the HMS Resolute became stuck on sea ice during the search. American whalers, however, rescued the crew, and the fated ship was returned to England. Interestingly, part of the ship's wood later became the source for the US White House's well-known Resolute Desk in the Oval Office.

A Tragic Modern History

In response to growing North American security concerns after World War II and the following Cold War with Russia, in 1945, Canada and the USA built a High Arctic Weather Station and an airstrip at Resolute. A Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) base was built in 1949. At that time, the population comprised only military personnel and specialist meteorologists from the south. No permanent settlements existed in the Resolute or Grise Fiord area until the mid to late-1940s.

Although today Resolute is an Inuit hamlet, the indigenous people did not settle in the area until the 1953 High Arctic Relocation, a shockingly sad and sorry chapter of modern Canadian history.

In an attempt to assert strategic sovereignty in the strategic political High Arctic, the Canadian government forcibly relocated several Inuit families from Nunavik in northern Quebec to Resolute and Grise Fiord.

The first group included only one Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer, Ross Gibson, who was to become the community's first teacher.

The Inuit were taken on the Eastern Arctic patrol ship CGS Howe to areas on Cornwallis and Ellesmere Islands, both barren, uninhabited regions in the hostile polar north - some of the coldest and most treacherous regions on earth. Only while the Inuit were on the ship did they learn they would not be living together but separated into three groups at three locations.

The Inuit were promised improved living opportunities, homes, and game to hunt. They were also promised a free return to their original locations after one year, should they wish. But on arrival, there were no buildings and very unfamiliar wildlife to hunt. The families were left with insufficient supplies of food, caribou skins and other materials for making appropriate clothing and tents, and suffered extreme deprivation in the first years after relocation. Some only survived starvation because they were close to the American base, whose personnel gave them food.

A second group was forcibly relocated in 1955 from Inukjuak, Quebec and Pond Inlet (then part of the Northwest Territories, now Nunavut) so that they could teach the Inuit how to survive in the unfamiliar, severe environment of the High Polar Arctic - and where there was no sunlight for many months of the year.

The government withdrew their promise for the Inuit to return to the lands, even poisoning their dogs to prevent them from escaping. Eventually, the Inuit learnt to hunt beluga whales and local wildlife, but many perished during their harsh existence. It was a brutal experiment and a shockingly shameful act by the Canadian government against these people.

Sadly, this sort of treatment was not restricted to the Canadian authorities or the indigenous people of the High Arctic. Australia is also responsible for its share of discrimination, brutality and genocide.

In 1993, the Canadian government held hearings to investigate the relocation program, and the following year, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples issued a report, The High Arctic Relocation: A Report into the 1953-55 Relocation. The government paid CAD 10 million to the survivors and their families. A formal government apology was made in 2008.

Later, the government of Canada apologised to the Inuit for the mass killing of their sled dogs in the 1950s and 1960s, which devastated communities by depriving them of the ability to hunt and travel.

AN AFTERNOON TOUR WITH QUENTIN

There was no doubt about it. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police we met in Nunavut were delightfully friendly and helpful. As promised, Quentin picked us up from South Camp Inn in the early afternoon, driving south of the hamlet along the coast of Resolute Bay, opposite Griffith Island and near Ruins and Resolute Lakes.

On a bitterly cold and overcast day, our journey was accompanied by flurries of snow and driving winds. I am unsure what the temperature was, but it must have been around minus 20 °C. And with the wind chill factor, it was more like minus 40 °C... We find it easiest to determine how cold it is by how long it takes your eyelashes to freeze. As we were to find, it was not long at all!

After twenty minutes or so of following the southern coastline, Quentin pulled our vehicle over the side of the road. As we crunched through ice and snow in freezing conditions, we could just make out a life-sized granite sculpture of a parka-clad Inuit figure looking intently to the south. Covered in snow and icicles, it exuded a hauntingly eerie and sad persona. On a large rock beside it was an engraved bronze plaque

The carving was a monument to the Inuit who were forcibly relocated to the High Arctic in the 1950s by the Canadian government. In 2008, soon after the formal Canadian government apology, Simeonie

Amagoalik (1933-2011), a carver and community leader, was chosen to carve this statue to commemorate the

relocations. Today, the figure stands just a few meters from where Simeonie Amagoalik and his family first landed in one of the 1953 relocations. It faces south toward northern Quebec and Inukjuak.

The plaque reads: "In Memory of Inuit Landed Here in 1953 and 1955. They came to these desolate shores to pursue Government's promise of a more prosperous life. They endured and overcame great hardship and dedicated their lives to Canada's sovereignty in these lands and waters."

The plaque fazed me. The statement appeared so superficial, almost insincere. Yes, it acknowledged the great hardships endured by the Inuit, but one could hardly say they willingly dedicated their lives to Canada's sovereignty. And the poor captives who died didn't exactly overcome their terrible hardship. What would I have expected in such a dedication? Perhaps something about the apology?

It is bizarre that so many places we have visited that have been sites of terrible events possess an unlikely feeling of peace and calm. The sculpture and the shores where the captive Inuit landed in 1953 certainly exuded a strange yet sobering peace.

Within a short distance from the Inuit sculpture, Quentin showed us another yet quite different monument. A small round bronze plaque titled "Reaching Home 15,000 km" attached to a cement base was dedicated to the memory of Japanese adventurer Hyoichi Kohno.

In 2001, 43-year-old Kohno set off alone on an expedition from the North Pole to his home country of Japan. His journey was planned to be achieved by walking, skiing and kayaking. Just two months and 600 km into his trek, Kohno failed to contact his base at Resolute Bay. His body was eventually found about 50 nautical miles from Ward Hunt Island, on the very northern tip of Ellesmere Island, his legs entangled in the rope to the sled he was dragging. It is thought that he was attempting to cross an opening in the sea ice.

Kohno's adventurous career included climbing North America's highest mountain, Mt McKinley, crossing the Sahara Desert by foot and walking from New York to Los Angeles.

It was far too cold to be outside any longer. Alan, who had crazily walked from the car without his mittens, was beginning to show signs of frozen eye-lash syndrome and had become really uncomfortable. Recalling his many collapses in extreme cold conditions, it was time to return to Quentin's vehicle.

Quentin invited us to visit the RMPF quarters back "in town." On the way, we drove via the airport and the NAV Canada Weather Station, curiously resembling a Mexican hat.

At the police headquarters, we met again with Paul, whom we had met on our arrival at Resolute Airport. Together, he and Quentin talked to us about life in Resolute. Paul's wife and family had also moved there, their children attending the local school.

Their attitude, like Steve's back at Arctic Bay, impressed us. Their philosophy was positive: to assist the community and to try to prevent incidents from occurring before they happened. Crime, they said, was not a significant issue in the hamlet. And both held a deep respect for the Inuit culture. Later, we recalled that not once in Canada did we hear or come across any form of racism. Refreshing...

Of course, I just had to sit in one of the cells. Concrete, spartan and windowless, it was not a very pleasant experience.

On our way out, we met Paul's wife, Chelsea and their baby daughter, Grace, wrapped on her mother's back in a traditional Inuit baby sling. "How do you get her out?" we asked. "Well, like this," Chelsea said, tipping her head down and rolling the baby onto her lap. Amazing...

Quentin and Paul had been very good company, and we enjoyed meeting the gregarious Chelsea. We greatly appreciated our unexpected afternoon "tour" and the invitation to the police station. Quentin also offered to contact his sister in Iqaluit about our return trip and suggested we catch up again before we left. They were all friendly, generous and helpful people.

We were enjoying our stay in Resolute very much.

DAY 3

A Quiet Morning on a Glorious Day

Sheldon and Makpa were right. The day dawned a beautiful, clear and sunny morning. With no wind, it even felt slightly warm. Well, a balmy minus 15 °C! For better or for worse, we were committed to our afternoon snowmobile tour. And hopefully, we would see some polar bears.

I was still concerned about Alan, though. For some ridiculous reason, I almost felt it was my responsibility, even though he had made his own decision to go.

Alan hates me fussing, so I rang Sheldon as soon as I could be alone. He agreed that he was also concerned and had organised to tow a sled with a tent, an inside kerosene heater and hot drinks. If Alan became cold or dizzy, we could at least keep him warm and comfortable. I was relieved and grateful. This young man was very mature and thoughtful.

Over a slow breakfast, an Inuit man introduced himself and asked if he could sit with us. His name, he proudly told us, was Joadamee S Iqaluk - the "S" referring to "small ear" and his family name of "Iqaluk" meaning "fish." A delightful, quietly spoken and gentle man in his late 50s, Joadamee told us that his parents and grandparents had been part of the government's relocation program in 1955. While I was organising coffee for us, Joadamee told Alan about the horrific time his family had endured after leaving Pond Inlet. He was especially bitter about the mass slaughter of their dogs - their only transport and means of hunting what little they could find.

Joadamee was also part of the residential Program for school children. Like Roger Gruben, we met in Tuktoyaktuk and other friends who had suffered a similar fate in Arctic Russia, he had returned to Resolute from his school days, not part of white society yet feeling culturally estranged from his family.

Emotionally scarred from his experiences, he had suffered badly from the consequences of the relocations.

And even today, young people have mixed feelings about leaving the High North. Firstly, they mostly cannot find their chosen jobs without travelling to the larger centres. Once there, most cannot afford the astronomical cost of flying home, if only to visit their families. Of course, Nunavut has no roads to link villages or larger centres. Flying or travelling by boat in summer is the only means of long-distance transport. A perfect storm for a broken society; no wonder there are psychological and alcohol problems in Nunavut.

A Euphoric 60 km Snowmobile Experience Across Resolute Bay

Sheldon and Makpa arranged to pick us up by snowmobile at South Camp at 1:00 pm. As usual, it was difficult to know what to wear - and just as importantly, when to get dressed.

I mentioned in a previous chapter that dressing too early and becoming hot is dangerous. Once outside, in very cold conditions, perspiration freezes quickly and is a common cause of frostbite. But then again, it takes us forever to get dressed. And we could never work out an optimum time to begin the tedious process.

.

We opted to wear one set of upper and lower military thermals, thermal fleecy tops, padded over-pants, balaclavas, neck scarves, long scarves, our Russian ushanka fur hats, under gloves, thermal mittens, and to top it off, our new snow goggles. Oh, and of course, our Can-Cope-Down-To-Minus-40°C Snow-Boots. Why I didn't think to take chemical hand and foot warmers, I'll never know...

Sheldon arrived, equipped with a huge rifle and, as promised, pulled a sled behind his snowmobile. He took pains to ensure Alan knew we would be well cared for (I hadn't told him about my paranoid phone call...) He also said that he would stop periodically to check if everyone was traveling OK. Sheldon would pillion Alan while I would go with Makpa. I didn't mention that we didn't have helmets.

To our relief, we both hopped on the snowmobiles without any difficulty - or thigh cramps! Our snowmobiles - commonly known as "Skidoos" in Canada, were beautiful, strong machines. Surely, Alan couldn't roll one with Sheldon as the driver? But I never underestimate my accident-prone friend...

Note: There have been times when we have struggled embarrassingly with cramping when trying to lift our legs high over snowmobile gear. In one notable case in Mongolia, Alan cramped badly when dismounting his camel, to his dismay and our mirth, landing into a huge pile of camel diarrhea. But that is yet another Alan-Story-of-Woe...

Our trip took us immediately onto the frozen expanse of beautiful Resolute Bay, Sheldon leading and Mapka and I following behind the sled. Travelling fast by Skidoo over a frozen sea was profoundly liberating. In the far distance, we could see a faint, blurred outline of Somerset Island. The surface of the bay, although flat and seemingly smooth, was scarred with ripples made from wind as the water froze. Our ride was surprisingly bumpy. But thankfully, the Skidoo seats were well-padded and comfortable.

It was warm to begin with, and I found myself sweating profusely. But there was nothing I could do. What was worse - having frostbite or dying from hypothermia? Makpa said she felt the same.

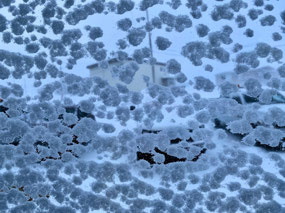

Our first stop was at a tall iceberg just out of Resolute Bay - and fair and square in the middle of the frozen seas of the Arctic Ocean. We could see the iceberg from our hotel room, but it was just a tiny pimple on the frozen sea surface. Up close, it was a majestic natural sculpture, intricately and ornately carved by the wild forces of wind and ice.

Taking photos in the extreme cold is always difficult, involving taking off my mittens and under gloves. Although the air temperature initially felt warm, removing my mittens soon became extraordinarily painful. But I couldn't stop... The iceberg was so very beautiful. Sheldon cautioned me not to go too close, as icebergs are notorious for being surrounded by unstable, thin ice. I was pleased he warned me. Meanwhile, Alan, feeling a little unsteady, sat on his Skidoo, huddled in his warm gear. Thank god we bought those 900 down-fill gold jackets, I thought... I noted that Sheldon had kept a close eye on him, asking often how he was travelling. Alan was, in fact, coping well.

Looking back to the mainland, Resolute was a series of tiny dots. It was amazing just how far we had come.

Our trip took us a long way over the ocean. It was certainly not a homogenous surface; large ridges and frozen ocean folds often made our journey quite complex. Sometimes, Sheldon would have to ride parallel to the ice walls to find a way through. We did not expect such formations in the middle of the frozen Arctic Ocean. In fact, it would have been very easy to become lost as once we were away from the coastline, there were no reference points to guide us. And being an almost seamless coastline and horizon, it was difficult to distinguish between land and sea.

Sheldon then told us that our trip was only the second time he had been out on the ocean without his father's guidance. I'm not sure we needed to know! But Sheldon was very careful, and we did feel safe with him. Similarly, Makpa would often stop to check how I was travelling.

In the distance were lumps of ice-covered land, which Sheldon told us were Lowther and Griffith Islands. It felt, and was, a very long way from anywhere. It was, however, truly glorious: a frozen desert against a deep azure sky and a now fading pearly sun. The feeling of such remoteness was nothing short of euphoric. We were now truly On the Edge of Nowhere!

Midway through our journey, we stopped to rest while Makpa and Sheldon enjoyed a cigarette. At that point, we would have been some 30 km south of Resolute. It was becoming bitterly cold. My poor hands were aching badly, and we began feeling uncomfortable.

While we were having hot chocolate and biscuits, I walked a little way and noticed some huge fresh bear prints. Sheldon became very interested and, to my absolute horror, told me he would "take it out" if he saw a polar bear. I would like to think he meant it would be for our safety if one got too close, but I was unconvinced. Sheldon was a true hunter. After all, he worked for and as an outfitter and hunter, not a travel agent.

I couldn't imagine witnessing an unnecessary bear murder. After all, we came to view them, not kill them. After that, I didn't bother looking for bear prints, and I probably would not have mentioned telling anyone if I had seen a polar bear. In fact, I became relieved we didn't see one.

Late in the afternoon, we turned for home. By then, the temperature had dropped considerably, and the conditions were made worse by a light breeze that cut like a knife as our Skidoos swept across the frozen sea. Sheldon kindly gave me his brand-new seal skin mittens to help warm my suffering hands. They took a while to work, but when they did, they were brilliant. He had other mittens, but once they were warm, I put my mittens back on and tried to forget about taking photos. And that was very hard to do in such an extreme and unbelievably beautiful environment.

Our journey back seemed to take forever, the sun just setting as we reached our South Camp Inn. It had been a magnificent journey. I loved every minute (well, perhaps minus the last half an hour!), despite the cold and no polar bears... And miraculously, Alan had survived without accident or incident.

Sheldon and Makpa came to our hotel while we organised to pay them. While there, we also met Devon, the owner of the outfitter business for whom Sheldon worked. Wearing an outrageous pair of polar bear fur pants, he was not hard to notice. At just 21 years old, Devon ran a successful outfitters' venture and a photography business. He was very popular with locals, and everyone at South Camp seemed to love him. From what we could see, he was a delightful young man.

Paying Sheldon using our bank's online direct debit system should have been straightforward. But it wasn't. It was so infuriatingly simple. All that was needed for the transaction was a mobile verification code. Our phone number, which our bank used, had changed with our new SIM card. Even if we had replaced the new one with the old SIM card, it would not have worked because we were in Nunavut, which had no coverage. We tried PayPal. We tried everything. Poor young Sheldon was looking sick. Conversely, Makpa was totally unfazed. After hours of trying, we said we would ring our bank that evening and see if we could obtain a verification code by email.

Before he left us, Sheldon suggested that we ring a local person called Aziz to see if he could help us. Perhaps, he had a merchant's account that would accept our many credit cards? Otherwise known as "Ozzie", Aziz was, in fact, the Mayor of Resolute. Regarded like a god to the locals, he was also a firm friend of Sheldon's father. Sheldon would ring him that night to explain our problem. But really? How could we ask someone to help us with a payment with whom we had never met? We just hoped that our St George Bank international banking helpline could assist.

Our bank consultant was very sympathetic and helpful, advising that she would waive the need for the verification code on this occasion. That sounded fine, but when she checked the bank's system, she could not undertake the waiver. Apparently, the Canadian government required the code, and sending the code by email was not an option.

To further exacerbate the problem, there was no ATM in town. By then, we had only a limited amount of cash because taxis and some other outlets in the north did not take credit cards. Telling poor Sheldon that we would, of course, pay him was not much consolation - especially as we still had around two weeks before we would be back in Australia. Perhaps we could solve the problem in Iqaluit on our way home? It would, at least, give us something to do... And then there was always Mayor Aziz.

Too much over-thinking, it was time to sleep on it.

Note: Since returning home from Canada, we have checked with St George Bank online banking personnel, who tell us that the Canadian government requirement for a phone code verification is not correct. It is our own bank's policy.

DAY 4 - BLIZZARD IN RESOLUTE

Saved by the Mayor of Resolute

The evening before, Sheldon had warned us of an impending blizzard. But believing on such a beautiful, calm, milky pink-sky night was difficult. After all, the saying goes: "Red Sky at Night, Shepherd's Delight". Well, it was pink and not red...

The following day, the blizzard was ferocious. As we looked out of South Camp windows - when we could see out of them - people were struggling to stay upright just to stagger a few meters to their vehicles. Winds were near 130 km per hour, and snow fell thick and fast...

But there was no time for window gazing. We talked with South Camp's administrator Dorothy, with whom we had struck a very pleasant relationship, about contacting Mayor Aziz. There was no way that we could leave without sorting out Sheldon's payment. But asking this sort of favour from a complete stranger did not sit well with us. Dorothy was very laid back. In her opinion, we would be right to contact him, and she did not doubt that he would sort something out. It seemed that poor Mayor Aziz, regarded as a god, was also treated like God!

Within seconds of contacting Aziz, he confirmed it was no trouble for him to pay young Sheldon and that we could pay him when we returned home to Australia. Astonished that we would meet an absolute stranger willing to help us in a very embarrassing financial situation was nothing short of a miracle. Perhaps Mayor Aziz was God?

Later in the day, we met Aziz at South Camp. A lovely man, he reassured us that we need not worry about him loaning money to total strangers (and to stop calling him "Mayor Aziz").

If we did not re-pay him, the next person in similar trouble would not get helped! We later found out that we were not the only persons staying in Resolute who had been in a similar situation and that he had always helped them. And, the money was always re-paid. It was a huge relief.

Aziz Kheraj was a most interesting man. Of Indian heritage, he was originally from Tanzania, where he initially trained as a mechanic. In 1974, with just $50 in his pocket, twenty-year-old Aziz travelled to Canada to find a job in the Arctic.

Interestingly, Aziz met his wife, Aleeasuk in the 1980s when she was Mayor of Resolute! Later, Aleeasuk established a business to become the North's only female commercial polar bear hunting guide.

Aziz was later appointed as Mayor. He prospered as an entrepreneur in the Arctic, eventually owning two hotels (the South Camp Inn and the Airport Hotel) and a construction company in Resolute. As Canadian polar legend and commentator Richard Weber said, "If Ozzie were to disappear tomorrow, they would have to call the army to run Resolute!" (excerpt from article "Last Stop Before the North Pole" at https://margopfeiff.wordpress.com). It was little wonder that Aleeasuk and Aziz were highly regarded in this community.

In 2012, the ATCO Group bought Aziz's business, South Camp Enterprises. Today, Aziz remains the Mayor of Resolute and continues to play an integral role in running the hamlet.

"Be Careful What You Wish For..."

Our other issue was the weather. The blizzard was intensifying. Snow completely covered South Camp's external stairs and had begun to build thickly onto the vehicles parked just outside.

We were due to fly to Iqaluit the following day, but ATCO workers at South Camp were not hopeful that our flight would even get to Resolute, given the forecast. We had not heard anything about our flight to Iqaluit. We were advised we would probably not be notified until the next morning. Had my dream come true?

"Be careful what you wish for. If we get snowed in for too long, we might miss our connection with our flight from Vancouver to Sydney", said Alan darkly. At that stage, I was not at all concerned. Even if our flight was cancelled, we would most probably only spend an extra day or so in Resolute. And we still had a buffer of a few days before our flight from Iqaluit to Ottawa. I was not-so-secretly delighted.

As the day progressed, the blizzard only became worse. By the afternoon, Resolute was in a whiteout.

Meanwhile, we were enjoying a restful afternoon; neither of us was barely able to walk after our snowmobile trip...

DAY 5 - OUR FLIGHT TO IQALUIT IS CANCELLED

From Delight to Drama...

At 2:30 am, we received notification from Canadian North that our flight had been cancelled. Initially, we were relieved that we didn't have to pack. And of course, I was delighted to spend extra time in Resolute...

At breakfast, however, we received the more disturbing news that we couldn't fly out of Resolute until 15th April - another six days and another CAD 6,000 for accommodation. We were wait-listed for the next few days but were told it was not at all likely that we could obtain a seat. This meant we would miss connecting flights from Iqaluit to Ottawa, then to Vancouver, and our flight back home to Australia. It certainly wiped the smile off my face...

By good fortune, Dorothy had mentioned that she and several other staff would be flying out the coming Friday to Yellowknife by charter flight. They were at the end of their eight-week shift and looking forward to returning to their respective homes.

Dorothy suggested that if it suited our travel arrangements, we may be able to obtain seats on the flight. "But you would have to ask Ozzie", she added.

As it happened, Aziz had the contract for transporting all ATCO fly-in fly-out staff and the logistics of transporting all supplies to the hamlet. This man was quite extraordinary. But once again, we would need a favour from him... We just hoped that we could pay him through a merchant account...

Within seconds, Aziz replied. Yes, we could book seats on the coming flight to Yellowknife. It would cost us CAD 3,000 per person. There was, he emphasised, no trouble in paying him when we arrived back home in Australia. We looked at each other, "Oh god! We now owe Aziz CAD 7,000."

Note: CAD 3,000 per person may sound like an outrageous cost for this airfare. But as we found, prices are extraordinarily high in the Arctic.

Flying back to Vancouver via Yellowknife suited us perfectly. Neither of us was keen to visit Ottawa and certainly did not want to spend five days in Iqaluit. Best of all, we had another three days we could enjoy being in Resolute. We liked Yellowknife and were looking forward to perhaps catching up with some of the people we met there on our forward journey.

How lucky could we be? We had the best of all worlds. Well, that was assuming our travel insurance would cover most of the additional costs...

Resolute, Nunavut, Canada

Resolute, Nunavut, Canada

2025-05-22